As COVID-19 shuttered public life in the United States, the AHA geared up to document the many ways that historians responded to the crisis. Tom Barrett/Unsplash

While historians of the 1918 flu may have been surprised by how few headlines the centenary of its outbreak made in 2018, it made hundreds in 2020. With the outbreak of COVID-19, the history of epidemic and pandemic diseases suddenly became relevant to daily life. References to the 1918 flu, along with other past epidemics and pandemics, appeared ubiquitous in the media. And so did the historians of medicine and science who study them.

Initially, the objective was to compile a list of vetted articles and resources written by historians on the history of epidemics and pandemics that could be featured on the AHA’s website. Given that historians in general, and the AHA in particular, recognize that everything has a history, it quickly became clear that it wasn’t just historians of medicine and science whose scholarship had struck a chord of public resonance in the wake of the pandemic. The economic crisis following the enforcement of quarantine measures brought the work of economic historians to the fore, while historians of gender and labor unpacked disparities within and between the realms of “essential” and “remote” work. Political historians offered guidance on how to navigate the new meaning of rights and restrictions in a pandemic. All the while, historians of race denounced the disproportionately devastating impacts of COVID-19 on communities of color across the United States. In short, every aspect of the COVID crisis had its own unique history.

Since it has been vetted, the bibliography can reduce the amount of time and guesswork for those in search of historically informed materials on the pandemic.

The bibliography catalogues these various histories for posterity and makes them accessible in one place. One of the early challenges for teachers, students, journalists, and policy makers searching for historical perspectives on COVID was the problem of tracking down reliable materials. A basic internet search on “the history of pandemics,” for example, yields thousands of items, leaving one to sift through endless entries of questionable credibility. Since it has been vetted by experts, the bibliography can reduce the amount of time and guesswork for those in search of historically informed materials on the pandemic.

AHA staff have reviewed every entry featured in the bibliography. Led by Sarah Jones Weicksel and , who both joined the AHA as NEH CARES–funded research staff, the bibliography team confronted its first major challenge in determining which references to include or exclude and how to make those decisions. Determining the terms of inclusion for any project is fraught with difficulties and implicit biases, making the matter both decisive and delicate all at once. Fully aware of these issues and given that the project specifically features historians’ responses to COVID-19, the bibliography team deferred to the AHA’s Statement on Standards of Professional Conduct to shape its vetting policy. It is for this reason that the bibliography exclusively features authors whose work adheres to the core values of historical inquiry shared by all historians.

Another vexing challenge in compiling the bibliography was deciding how to meaningfully organize its numerous and varied references.

This standard ensures that each reference included in the bibliography investigates and interprets the past as a matter of disciplined practice by offering a critical assessment of primary sources, maintaining accuracy in communicating information, and rigorously contextualizing that information to convey its broader significance. In a culture where people are highly skeptical of “facts” and “truth,” those who draw on the bibliography can rest assured that its references are indeed credible.

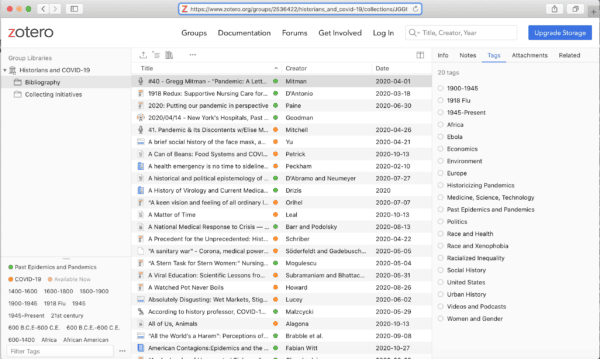

The “Historians and Covid-19” Zotero Library allows users to search by tags that include diseases, locations, and time periods. Screenshot by Melanie Peinado

Another vexing challenge in compiling the bibliography was deciding how to meaningfully organize its numerous and varied references. At the outset of the project, the bibliography team organized entries according to a primary “response type”—“Government Responses,” “Public Responses and Human Experiences,” and “Medical and Scientific Responses.” Historians’ steady production of materials quickly outpaced the initial taxonomy, prompting the creation of two additional categories, “Global and Historical Perspectives” and “Primary Sources and Teaching Tools.” Following the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement in late May, the number of references dealing with themes of “Race and Health” generated an entire category of its own. Finally, the efforts of historians working in museums, archives, and libraries across the country to preserve the pandemic’s diverse primary source materials constituted the bibliography’s newest category, “Collecting Initiatives.”

The constant evolution in both the bibliography’s form and content reflects its nature as a living document. Born out of historians’ efforts to harness their expertise for the public good and developed over the course of an “unprecedented year,” the bibliography’s 400 references (and counting) are a testament to the fact that no crisis and no year is immune to the precedent of history.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.