As literary scholars who work with both print and digital materials, and are interested in the production, construction, and materiality of texts, we believe that a book history approach reveals crucial information about the impact of race on what print materials are digitized. As Earhart has documented in “Can Information Be Unfettered? Race and the New Digital Humanities Canon,” there are clear inequities in our digitization of materials that break along the lines of race and gender. Our interest in black book history led us to teach a stacked undergraduate and graduate course, Race, Print, and Digital Humanities, in the Department of English at Texas A&M University. We wanted our students to apply the methods of book history—enumerative bibliography and scholarly editing—to the African American literary corpus.

Often, our discussion focused on access. What opportunities did African American authors have to create and distribute their work? What efforts have scholars made to provide access to African American texts, both in print and digital forms? What does book history tell us about how or why the texts are preserved? As both textual scholars and digital humanists have learned, editorial and technical decisions are not without bias. Through a series of case studies, students learned that bibliographical scholarship is not neutral and, in the case of African American literature, efforts to provide access to literary and other texts can either reify exclusion or serve as forms of activism. As Arthur Schomburg argued in “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” the collection of black texts is in and of itself a re-articulation of the centrality of African American thought in American culture and an activist act, and that our re-articulation of the centrality of black bibliography is part of a long history of activism.

Our class was structured to allow for both theoretical discussions regarding scholarly texts as well as hands on activities to engage students with concepts that arise when “doing” digital humanities. Topics included “Race and Publishing Blackness”; “How to Make, Evaluate, and Use a Bibliography”; “Bibliography as Recovery”; “Textual Problems: Non Traditional Texts”; “Forms: Words, Music, and Images”; “Multiple Editions/Versions”; and “Annotations and Paratexts.” Each topic included a case study that allowed students to test their theoretical knowledge. For example, when we discussed multiple editions and versioning, students used the Juxta tool to compare versions of Martin Delany’s Blake. When we examined “Forms: Words and Music,” students read James Weldon Johnson’s God’s Trombone and examined multiple musical scores of his included works.

Materiality and Publication

Early in the semester students explored the work of David Drake (c. 1801–c. 1871), widely known as “Dave the Potter,” and sometimes as Dave the Slave. An enslaved potter, Dave produced over 100 everyday jars and pots on which he inscribed brief poems. An increasingly studied figure, Dave’s work allowed us to discuss how materiality impacts the reception of texts.

After examining images of the pots; a children’s book on Dave, Dave the Potter: Artist, Poet, Slave; and selected poems, we asked students to imitate Dave by creating and inscribing text on small pots that they made with modeling compound. Each student shared their pot with a neighbor, who read the inscription.

This activity provoked discussion about how scholars deal with physical objects that include text. The challenge of inscribing their own pots helped students consider the interplay of medium and text (could the difficulty of inscribing certain letters influence Dave’s word choices or spelling?). Similarly, the difficulty of reading each other’s inscriptions highlighted the complexity of transcribing and editing Dave’s texts. What is changed—or lost—when a poem originally inscribed on a five-foot pot is translated into a line of poetry in a printed book? Students quickly noticed another consequence of Dave’s medium: because he wrote poems on everyday objects instead of publishing them in a printed book, he was dismissed as a poet for 150 years.

Annotations and Reader Responses

We were also interested in having students understand what reader responses, particularly annotations, might tell us about the text. Accordingly, we had students conduct a case study, based on the Book Traces Project, which provided an opportunity to learn about transmission and annotation. Scholars have long understood that a book’s “meaning” is impacted not only by its transmission but by the interaction of the reader with the book, often through permanent markers such as annotations. This activity allows students to search for responses in their localized university context and to speculate on what annotations might tell us about transmission and reputation of texts.

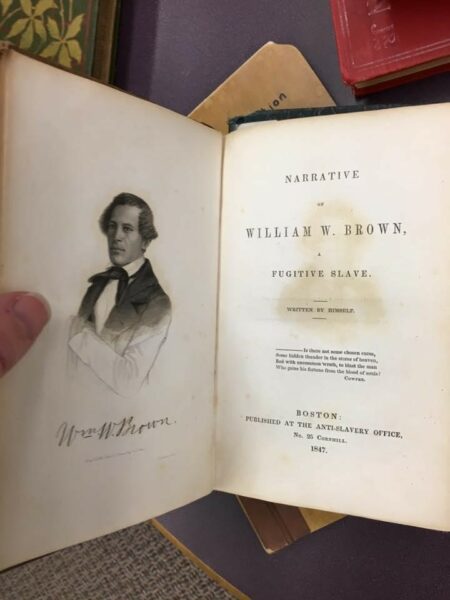

Led by Andrew Stauffer, Book Traces asks participants to go into circulating library stacks and look for pre-1923 books that have been annotated. Our students went to our library, looked for books that discussed Africa and African Americans, and discovered a number of important books stored on the library’s open shelves. One student, Melissa Filbeck, located a first edition of William Wells Brown’sNarrative of William Wells Brown, A Fugitive Slave (1847):

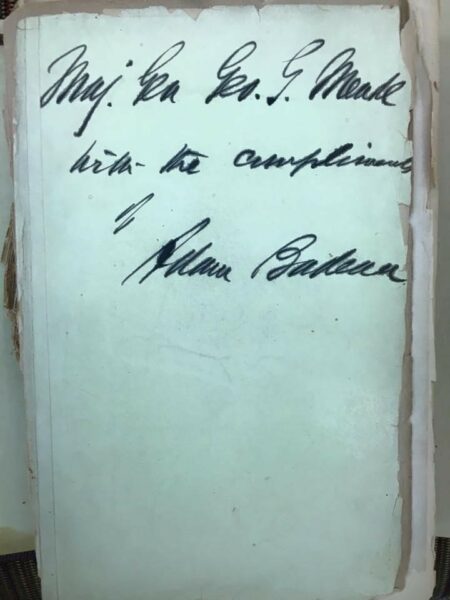

Another student, Derek Brown, found an inscribed presentation copy of an analysis of Ulysses S. Grant’s military history that had been presented to Major General George G. Meade:

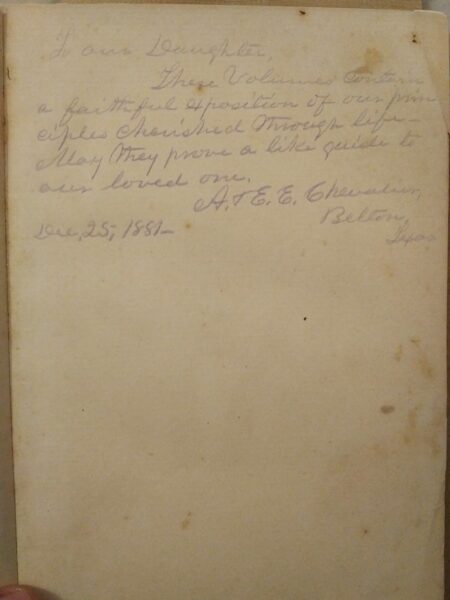

Fascinated by an inscription on Jefferson Davis’s The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government (1881), another student, Aaron Atkinson, traced the woman to whom it was presented. In an impressive feat of research, the student revealed that the woman is the great grandmother of the actor Chris Pine. While the finding might not alter scholarship, it proved a pivotal moment for students in the course in that it linked contemporary culture to the scholarship of annotation and spurred undergraduate students like Atkinson to feel the thrill of research and discovery.

In blog posts, students considered how the annotations they discovered—themselves historical artifacts—reflected contemporary readers’ responses (sometimes verging on re-writings) of the texts. In the case of Jefferson Davis’s The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, the pro-Confederate sympathies of the inscription are clear. Written and presented in 1881, at a moment when Reconstruction has ended and Jim Crow was well underway in Texas, the book inscription reinforces the message of the volume—a justification of the Civil War and a longing for the so-called “peace, order and civilization” that Davis claimed came with slavery. The inscription reinforces the message of the volume and reveals just how deeply entrenched segregation and racism was in Texas.

Publication Histories and Editing

Another thread that we grappled with during the semester was how editing, and what we choose to edit, might be considered a form of activism. Students read and discussed the publication history of numerous texts central to the African American literary canon including Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes were Watching God (1937), Frederick Douglass’ Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself and My Bondage, My Freedom (1845), Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), and Martin Delany’s Blake (1851, 1861–62). Of these volumes, though, only Douglass has been given careful editorial consideration.[1]

We discussed how the lack of editorial attention to such texts has led to misreadings of the materials. For example, in “Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin: A Case Study in Textual Transmission,” Wesley Raabe revealed how unreliable most Stowe editions are due to a lack of careful critical attention, with misreadings of Aunt Chloe’s children and their travails under slavery due to shifts in names from “Mericky” to “Polly” without editorial clarification. Students were shocked to learn of the lack of editorial attention provided to Hurston, certainly one of the central 20th-century African American writers. Such activities revealed to students that often dismissed discussions of editing and editorial theory are actually central to how scholars read and assess texts. To treat the editorial decisions of African American texts seriously is to reveal the importance of the texts, an activist act.

Through these and other activities, our students examined how race is (and is not) accounted for in scholarly efforts to define, list, edit, and provide access to African American texts. Through careful engagement with a broad selection of textual case studies students recognized that book history approaches could unpack the complexities of racial construction.

[1] Fortunately Delany’s Blake has been edited by Jerome McGann and published by Harvard University Press as this post was in review:

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Amy E. Earhart is associate professor of English at Texas A&M University. She has published Traces of the Old, Uses of the New: The Emergence of Digital Literary Studies as well as numerous articles and book chapters on digital humanities.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.