The Zika virus has recently announced its unwelcome arrival in the continental United States. In addition to over 2,500 individuals who have contracted the disease abroad, some 50 locally generated cases have been confirmed in Florida. Many more cases are anticipated. With the public health resources needed to combat the disease running dry, the administration has requested $1.9 billion in emergency funding. As usual, however, Congress is gridlocked, and it’s anybody’s guess whether a funding bill will pass before members leave Washington to campaign for reelection. (For the history of Congressional partisanship, see the video and blog post from the Center’s briefing on the topic.)

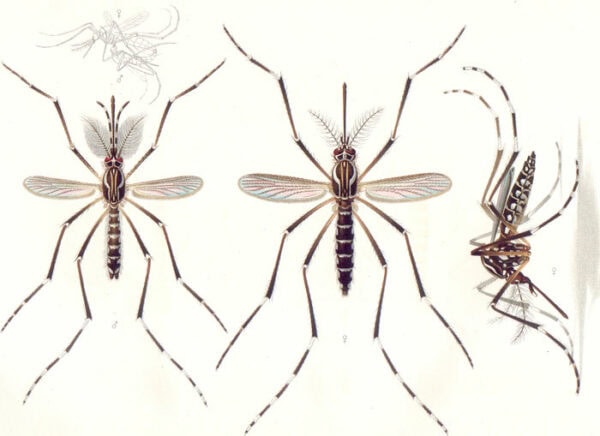

1905 print by E.A. Goeldi of the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Wikimedia commons.

It’s in this context of compelling need and congressional inaction that the National History Center sponsored two briefings earlier this month on “Zika: Historical Parallels and Policy Responses,” one for House staffers and the public, the other for Senate staffers. Two leading historians of mosquito-borne epidemics in the Americas, Margaret Humphreys of Duke University and John McNeill of Georgetown University, presented the briefings, with Alan Kraut of American University moderating the House session.

John McNeill opened the briefings by explaining which mosquitoes spread the disease and what measures have been taken to control them. The primary vector is Aedes aegypti, which happens to be especially fond of human blood and human habitats. (Another mosquito, Aedes albopictus, also carries the virus, but it is less discriminating about the creatures it bites, making it less of a threat to humans.) Aedes aegypti also transmits yellow fever and dengue fever, which means that it has been a deadly houseguest long before Zika became part of its biological arsenal. This history has given us plenty of practice combatting our winged foe. Public health officials learned early in the 20th century that they could prevent Aedes aegypti from reproducing by emptying water containers or adding a few drops of kerosene to the water’s surface. By midcentury, newly developed insecticides provided an additional weapon against the mosquito. Many, however, posed environmental dangers (DDT being the most notorious example) and mosquitoes gradually acquired resistance to them. By the 1970s the Aedes aegypti had begun to bounce back, laying the foundations for the current crisis. In the short term, McNeill concluded, the only viable response to the threat from Zika is renewed mosquito control.

Margaret Humphreys shifted the focus of the briefings to the lessons that can be learned from past public health initiatives to similar epidemic diseases. She pointed out in her opening remarks that legislatures are most responsive to “panic” diseases—those with gruesome symptoms that cause high mortality. Zika doesn’t measure nearly as high on the “panic” meter as, say, Ebola or SARS. (In 2014, the Center held a Congressional briefing on the historical roots of the recent Ebola outbreak. Please follow these links for the video and blog summary.) Although it can cause terrible birth defects, which understandably scare pregnant women, most infected people don’t get very sick. Many members of the public are more fearful of the health and environmental risks posed by the use of insecticide to kill mosquitoes than the mosquitoes themselves. In Miami, aerial spraying has already provoked protests. Trying to convince people to take precautions against mosquito bites through public education campaigns is a hard sell as well, especially in multicultural societies where different languages and medical practices are prevalent. Another complicating factor is that Zika can be transmitted sexually, which has historically presented an entirely different set of challenges for public health officials. Finally, the fact that fetuses suffer the most severe damage from infection means that Zika intersects with one of the nation’s most contentious issues—abortion—thereby complicating efforts to finance public health initiatives, as Republicans’ anti-Planned Parenthood rider to the funding bill has shown.

Wouldn’t it be nice, then, if medical researchers could simply develop a vaccine? Sure, but this is likely to take at least two years to develop. Even then, there’s no assurance of success: scientists have never been able to produce a vaccine against dengue fever, which is in the same flavivirus family as Zika. So at present, and perhaps into the foreseeable future, our only option appears to be mosquito abatement. Both speakers stressed that the success of such measures depends on the compliance of civil society, which is problematic in the present social and political environment. Still, the story of public health responses to earlier mosquito-borne diseases in the Americas demonstrates that they can achieve significant results. Furthermore, the failure to act could be catastrophic. Humphreys reminded her audience that the drug thalidomide produced large numbers of terribly deformed babies in the 1960s. She asked: will Zika be the thalidomide of our generation?

The National History Center’s Congressional Briefings program aims to provide members of Congress and their staff with the historical background needed to understand the context of current legislative concerns. A video recording of the “Zika: Historical Parallels and Policy Responses” briefing can be viewed at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GE6Z7LvSghY&feature=youtu.be

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.