Outwardly, President Obama’s election changed things for my students. They now proudly referred to the president with the possessive “my” rather than the article “the.” Obama buttons, t-shirts and hats became prized fashion accessories. And a few students even trekked from Brooklyn to Washington to witness the new president’s inauguration address. But however passionately they may have embraced the new occupant of the White House, my students saw themselves as fundamentally estranged from politics in general and policy in particular. This is not to say that they were unaffected by the financial crisis or the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but rather that they viewed politics as something foreign, something that wealthy, white men did in Washington. Obama’s candidacy increased their interest in the presidential campaign, but it did not mean that they saw lawmaking as something in which they were involved—a give-and-take between the people and their representatives.

The same was true with the way that students approached the study of American history. For them, political history—indeed history of any kind—meant the rote memorization of bill names and dates. At best, my students understood political history as something in which only certain elite subsets of the population participated. At worst, political history meant trivia. Of course this rendered political history boring. In their high school textbooks they would have encountered bolded terms and tidy glossaries. The Peace of Paris officially ended the French and Indian War in 1763. The Stamp Act Congress met in 1765. The Tea Act went into effect in 1773. Shots were fired at Lexington and Concord in 1775. Were these things equally important? It was easy to think so, glancing at the equal-sized entries deposited across neat timelines. The years came to assume more importance than the sequence. The result was that one event seemed to have no relationship with another.

I struggled to explain to my students that political history was more than this—more than simple, politician-centered explanations for complex historical forces and events. The Bill of Rights was not simply adopted because George Mason wanted it. Andrew Jackson did not usher in an era of universal manhood suffrage. And Andrew Johnson was not alone in ruining the promise of Reconstruction. Each man was surely important, but none operated in a vacuum. The subtext of high school textbook sidebars devoted to “Women of the Revolution,” “Slave Resistance,” and “Native American Culture” was that the lives of ordinary people changed only when an individual leader ordained it.

No wonder political history appeared boring to my students. If that was, indeed, the case, that change in history was due entirely to great individuals, then why should my students read the newspaper, let alone write to their legislators? Why should they engage in political discourse?

I set out to convey a simple truth to my students: Just as they didn’t know what the future would hold, the historical actors of the past didn’t either. Everyday people—including those who were not even permitted to vote—engaged in politics every day. To be sure, they were circumscribed in how much impact they could have on state decisions, but they were deeply concerned about those decisions, and those concerns formed the basis of everyday conversations—and of politics.

Conveying this idea proved difficult. I tried a variety of approaches. I had students read contemporary newspaper articles in an attempt to show that the tariff was something discussed in the public sphere, that pages and pages of ink were spilt to describe the implications of the Fugitive Slave Act. I had students look at diary entries of a slaveowner lamenting Lincoln’s election. I had students make lists of the political constituencies that developed during the Second Party System. But none of it seemed to bring home the idea that politics was lived. Students regarded such accounts as extraordinary, not the stuff of daily banter.

Figure 1: Engraving by Paul Revere, showing the massacre in King Street, Boston, on March 5, 1770. Digital image courtesy the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

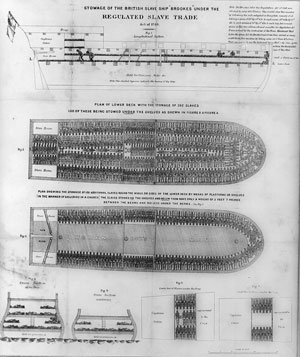

Finally, I turned to political prints. I had used images in the classroom before. Indeed, a driving factor in my choice of textbook—Who Built America?—was the range of images and detailed captions it included. I had had the class glance at Paul Revere’s famous illustration of the Boston Massacre (Figure 1) in order to show that so-called eye-witness accounts could be plagued with inaccuracies.1 We had examined the late 18th-century diagram of the storage of human cargo on the British slave ship, the Brookes, to discuss the conditions of the Middle Passage (Figure 2). And occasionally I included a quiz question related to an image in order to make sure students were “reading” everything that had been assigned. But we hadn’t looked deeply. We hadn’t considered the political use of images—why and how the drawing of the slaver was claimed by the abolitionist movement, or to whom Revere’s etching may have been distributed.

Figure 2: Diagram showing the manner in which slaves were carried across the Atlantic in the British ship, the Brookes. Digital image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

We also hadn’t considered how such images might have been received. What effect might Revere’s depiction of unprovoked murder at the hands of British forces have had on viewers’ attitudes toward the Patriot cause? What images of the event—a “bloody massacre” in Revere’s illustration—competed with Revere’s? What was the relationship between the Brookes diagram, the end of the transatlantic slave trade in the United States and southern resentment toward use of the mails for distributing abolitionist literature in the years following? How had the American abolitionists of the 19th century appropriated an earlier image created by slave traders? How had they transformed the meaning of an image that was intended to demonstrate compliance with British law’s new attention to the on-ship conditions of transported human cargo? What were the implications of such a re-appropriation for how slaves were regarded by other Americans—both abolitionist and non-abolitionist?

When they began to consider such questions, my students’ attitudes toward political history began to change. I found that it was easier to get them talking about images than about traditional texts. Freed from complicated or foreign-sounding language and the instinct to commit words to memory for an upcoming exam, they could look at what was in front of them. To identify relevant prints, and to find discussion questions that tied in with my learning objectives for the class, I turned to the internet.2 While many sites were targeted at high school teachers, I found that I could adapt the lesson plans for college students already familiar with the narrative history presented in their textbook. Over time, I learned to begin the conversation not with a lecture on the politics of the moment, or a discussion of the artist or the publication in which the image had appeared, but rather with a simple question: What was happening in the image? What did my students see?

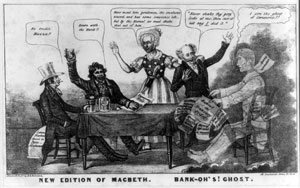

Figure 3: “New Edition of Macbeth: Bank-oh’s Ghost” A satirical caricature about the Panic of 1837, condemning President Martin Van Buren’s continuation of the policies of his predecessor, Andrew Jackson. Digital image courtesy the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

In many cases, it was not an easy question to answer. In the class period devoted to the Panic of 1837, we looked at a widely distributed print entitled “New Edition of Macbeth” (Figure 3). Seated at a table presided over by Andrew Jackson (in a dress!) were a southern cotton planter, a representative of Tammany Hall (pictured as a drinking Irishman), and the new president, Martin Van Buren. The Ghost of Commerce, his hands clutching a notice of the repeal of the specie circular and announcements of bank failures, sat at the end. This was not abstract theory, but a real, tangible (and nasty) attack on a former president and his sitting successor. Why was Jackson depicted as a woman? Why was Van Buren so small? What did the print have to do with the Panic of 1837? What was the artist, Edward Clay, trying to say? The cartoon gave us a platform for discussing the bank wars and the political coalitions of the Jacksonian period. It also allowed us to discuss why the artist and the thousands of people who bought, viewed and circulated his print cared about such things. Best of all for getting my students to think about what kind of political and cultural knowledge readers would have needed to understand the print, and the changing meanings of a reference over time, was the title’s Shakespeare allusion. My students began to rethink whether it was appropriate to impose their own notion of Shakespeare as a high school English class staple on the 19th-century subjects they were studying.

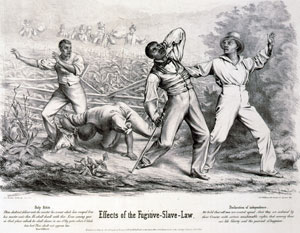

Figure 4: Effects of the Fugitive Slave Law. A lithograph from 1850. Below the picture are two texts, one from Deuteronomy: “Thou shalt not deliver unto the master his servant which has escaped from his master unto thee. He shall dwell with thee. Even among you in that place which he shall choose in one of thy gates where it liketh him best. Thou shalt not oppress him.” The second text is from the Declaration of Independence: “We hold that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” Digital image courtesy Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Using political prints in the classroom certainly may not work for all periods and contexts, and as a pedagogic technique it is not without its difficulties. I encountered three problems most frequently. First, students were sometimes unprepared to decipher visual modes with which they were unfamiliar. The heavy text, sloping script, and tableau-like nature of the Panic of 1837 print was common in the early 19th century, but it required decoding for 21st-century students accustomed to cartoons with exaggerated caricatures and sparse, easy-to-read text bubbles. Second, as with textual primary sources, some students believed that historical images carried authenticity—that they were true in viewpoint or in fact simply because they had appeared in print. If an 1850 print decried the Fugitive Slave Act, then everyone must have felt that way (Figure 4). Third, sometimes students were uncomfortable about speculating. If history was a series of facts, then how could we not know for certain what the author’s intent was, what the audience’s reaction might have been, or even who may have been in that audience? No textbook or lecture told them who the artist hoped would see his anti-Fugitive Slave Act print. So, my students wanted to know, how could I ask them to identify for an exam the intended audience for the print?

Yet despite these problems, I have found using political images to be helpful in demonstrating that the work of historians is often messy. More importantly, using political prints in the classroom is one way of engaging historical figures on their own terms, appreciating what politics meant at the moment, and insisting that politics mattered to everyday people. In the process, students sometimes reconsider both their understanding of history’s meaning, and their own relationship with politics at present.

< Previous essay | Next essay >

Notes

- Christopher Clark and Nancy A. Hewitt, Who Built America?: Working People and the Nation’s History, Vol. I: To 1877, 3rd edition (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2008). [↩]

- Among the most helpful were the American Social History Project’s “Picturing US History” project (available at https://picturinghistory.gc.cuny.edu); Edsitement lesson plan section (available at https://edsitement.neh.gov/); and the Library of Congress’ Prints and Photographs collection (available at https://www.loc.gov/pictures). [↩]

Rachel Burstein is a PhD candidate in history at the CUNY Graduate Center. From 2008 to 2010 she taught American and world history courses at Brooklyn College (CUNY). She thanks Joshua Brown of the CUNY Graduate Center and the American Social History Project for his comments on an earlier draft of this article.