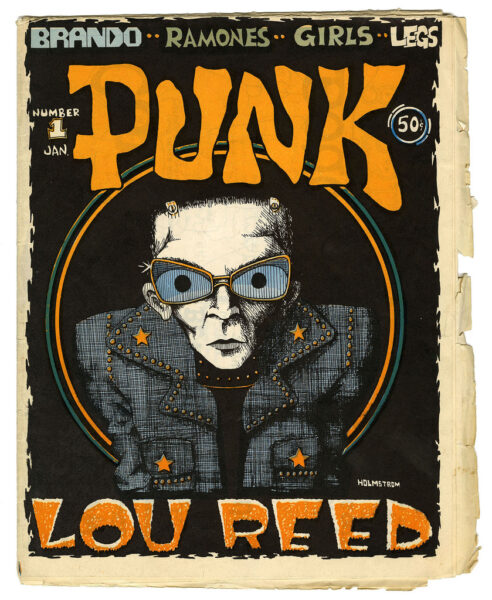

In April 1976, in the third issue of Punk magazine, John Holmstrom wrote, “Any kid can pick up a guitar and become a rock’n’roll star, despite or because of his lack of ability, talent, intelligence, limitations and/or potential, and usually does so out of frustration, hostility, a lot of nerve and a need for ego fulfilment.” Holmstrom’s editorial evoked the irreverent spirit of New York City’s punk rock scene, centered on CBGB, a club on the Lower East Side—but it also voiced Punk’s guiding philosophy. As a scrappy print publication crafted by amateurs, Punk was the embodiment of punk culture’s do-it-yourself (DIY) ethic: a firm belief that individuals should express themselves by creating their own culture on their own terms.

John Holmstrom

When Holmstrom and his friends Legs McNeil and Ged Dunn Jr. founded Punk in 1975, “punk culture” didn’t really exist as a describable concept. Rock critics like Lester Bangs of Creem had used the term to describe a raw, stripped-down style of rock music. But it was Holmstrom, the publication’s editor, who narrowed the cultural features of New York’s nightlife into something called “punk.” As McNeil recalled in Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk, “The word ‘punk’ seemed to sum up the thread that connected everything we liked—drunk, obnoxious, smart but not pretentious, absurd, funny, ironic, and things that appealed to the darker side.” With Punk magazine, its founders kick-started a publication as creative and zany as the scene they were documenting.

If you were a rock and roll fan living on the Lower East Side in the 1970s, you could have purchased a copy of Punk for a dollar or less at CBGB. Flipping through its pages—made of cheap newsprint or glossy paper—you’d find a wide range of coverage. You might have perused a feature proclaiming Marlon Brando to be “the Original Punk” or read a profile that screamed you just had to be there when Patti Smith or the Dictators performed at CBGB. You could have been inspired to thrift a leather jacket by Roberta Bayley’s iconic photographs of the Ramones, or laughed at one of Holmstrom’s comic strips, crammed with caricatures and juvenile humor. If you were lucky, you might have scored a special issue composed of photo comics: stories told through choreographed images of scenesters overlaid with speech and text bubbles. “The Legend of Nick Detroit” was an action-packed detective story starring Richard Hell, while “Mutant Monster Beach Party” featured Debbie Harry and Joey Ramone as its romantic leads. If you had a keen eye, you would have spotted Andy Warhol, Peter Frampton, and Joan Jett making cameo appearances.

Punk wasn’t built to last. As a DIY publication devoted to an underground culture, it had difficulty attracting sponsors, who probably weren’t impressed by its offbeat voice and inconsistent publishing schedule. A single issue was taxing to produce, and it showed. Articles were lettered by hand, as this made them cheaper to print than typewritten ones, and Holmstrom’s bold and comical illustrations—inspired by those of Mad magazine founder Harvey Kurtzman, his teacher at the School of Visual Arts—were already time-consuming before the cartoonist took over managing the entire publication’s operations in 1977. Punk shuttered in 1979 following the suicide of its primary financial backer, Thomas Forçade of High Times magazine.

However, this was far from the end for punk culture—thanks to Punk magazine. At its peak circulation, the publication printed over 23,000 copies an issue, but its reach went far beyond its physical distribution across the United States and the United Kingdom. Because of the magazine’s name, its staff were often the first to be interviewed by mainstream media outlets attempting to understand the culture. Punk also inspired a wave of DIY publishing that became the foundation of punk’s rich print culture. As Holmstrom recalls in The Best of Punk Magazine, his work directly inspired a boom in DIY publications including Sniffin’ Glue and Ripped and Torn in Britain, alongside Slash, Flipside, and Search & Destroy in California. Punk culture had only just begun.

Grant Wong is a history PhD candidate at the University of South Carolina.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.