A recent clear-out of my parents’ attic yielded not one, but two punch bowls, complete with dozens of matching glasses. All had been wedding gifts to my grandmother when she married in the United States in the early 1950s. “I don’t have room for them,” my sister texted, “unless I make punch my thing?” I encouraged her, because as it happened, I had a stack of 1950s punch recipes from my research into British drinking history.

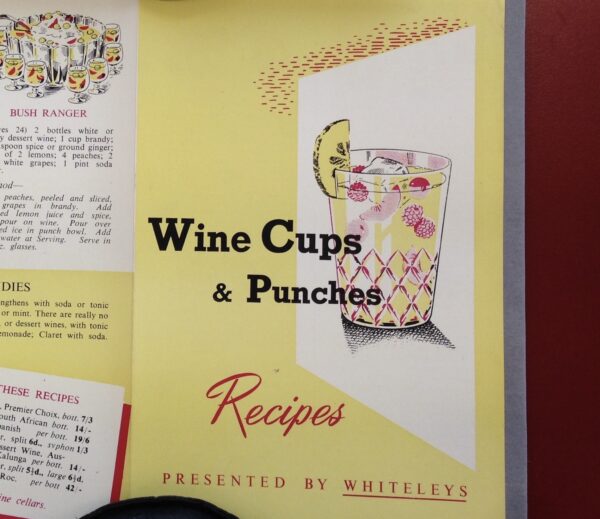

The Whiteleys recipe book reflects a new ear of postwar abundance in Great Britain. Westminster City Archives, UK

Punches have segued in and out of fashion over the past three centuries. In Britain, the term “punch” has been used regularly since the 18th century and referred to a batch-mixed drink consisting of some kind of alcohol with the addition of fruit juices and sugar. Punches were usually garnished with fresh fruit and could be served iced or hot (the hot toddy was also once called a punch). Although popularly associated with rum today, wine-based punches appeared over the 19th and 20th centuries in British women’s domestic guides and recipe books. Wine punch appealed to women who entertained: the drink stretched a bottle of wine to serve more people, could be prepared ahead, was relatively low in alcohol and thus prevented overindulgence, and looked pretty.

The 1950s were a moment of peak popularity for punch, and a British recipe for “Barossa Punch” tells the story of that particular era and its tastes and aspirations. I found the Barossa punch recipe featured in a promotional booklet for the department store Whiteleys, which catered to middle-class consumers in west London. A sign of the growing advertising industry and consumer society, the booklet contained original recipes and entertaining advice using the wines, spirits, and soft drinks sold in the store’s food hall. Printed in cheerful yellow and pink and illustrated with whimsical line drawings of cocktails, the booklet had a youthful accessibility that suggests it was aimed at newly married housewives. In the 1950s, most British women were married by the age of 24, and housekeeping was lauded as an art and a responsibility that came with matrimony.

Housekeeping was also an emotive issue, because in 1950s Britain one of the most important political and social issues was housing. Britain had long had a housing shortage for its growing population, which had been exacerbated by the wartime destruction of tens of thousands of homes. Moreover, as historian Claire Langhamer has shown, the wartime experience, in which many British people lost or were separated from their homes, prompted a new appreciation and yearning for domesticity in the 1950s and highlighted the substandard quality of much housing stock. While an indoor bathroom was still a luxury for much of the population, those who had their own homes—especially young married couples—cherished them. The Whiteleys recipe booklet leans into this excitement, encouraging housewives to entertain at home and promising accessible elegance.

Whiteleys’ drink recipes came at a moment when British people were rediscovering culinary abundance after years of wartime deprivation.

Whiteleys’ drink recipes also came at a moment when British people were rediscovering culinary abundance after years of wartime deprivation, as food rationing ended in 1954. Barossa punch was a simple recipe of red wine, fruit juices, sugar, soda water, and a garnish of fresh fruit and cucumber. The liquids were available year-round, though the garnish would only be widely available (and affordable) in season. Making the punch involved the simple skills of slicing and stirring, because the liquids could be purchased in the specified recipe units and thus required no measuring.

Barossa punch’s name nods to another hot button political and social issue of the postwar era: the changing status of the British Empire. India and Pakistan won independence in 1947 and Ghana in 1956, to be followed by dozens of other states through the 1960s and 1970s. As millions around the world rejoiced at the end of formal colonialism, many British people felt uncertain about their nation’s status in a changing world order. Barossa punch draws on an old bond of empire, that of the white settler population that controlled the federation of Australia. Barossa is a valley in South Australia outside the city of Adelaide and by the 1950s was an established major wine-producing region. Since the 19th century, the British market had been the major export destination for Australian wine, which was especially suited to the middle-class market for inexpensive wine. With Australian wines and the Barossa punch recipe, the British could get a taste of a far-away, sunnier clime, but also the reassurance of Anglo bonds of brotherhood. It was a bit exotic, but not too foreign.

The cost of this punch, which served 24, would have been about seven shillings, in a period where the mean grocery expenditure per person was around 26 shillings a week.

It might be surprising, then, that the recipe specifies “claret or burgundy” wine. Claret is a British term for red Bordeaux wine. To a wine connoisseur today, this suggests a surprisingly lax attitude towards provenance (the red wines of Bordeaux and Burgundy are made from different grapes and have very different taste profiles), not to mention the gastronomic crime of adding 10 ounces of lemon juice. However, in the 1950s the words claret and Burgundy were not legally protected, and Australia produced many “burgundy” and “claret” wines for Britain at much lower prices than French wines (at lower quality, too, some connoisseurs grumbled, but then another advantage of punch was that it could hide or improve the taste of an indifferent wine). Whiteleys sold Australian “burgundy” in flagons (40-ounce bottles) for as little as two shillings and ten pence, which was 25 percent cheaper than the cheapest French red. The cost of this punch, which served 24, would have been about seven shillings, in a period where the mean grocery expenditure per person was around 26 shillings a week. The real luxury in the punch was not the wine, but the fresh fruit.

In full commitment to research, I made Barossa punch using an inexpensive Australian Shiraz, although I scaled the recipe to a single serving. The verdict: If you like sangria, this was fizzy and fun, but I certainly wouldn’t subject a good wine to that much lemon juice. Punch was last in fashion in the 1980s, and my reading of history tells us it will come back eventually. I texted my sister: “I’ll take the punch bowls.”

Recipe

Barossa Punch2 bottles burgundy or claret [40 ounces]1/2 pint lemon juice [10 ounces]1/2 pint orange juice [10 ounces]1/2 cup sugar4 sliced peaches1 sliced orangeabout 2 dozen halved strawberries or equal number raspberriesdiced pineapple3 pints soda water [60 ounces]

Barossa Punch2 bottles burgundy or claret [40 ounces]1/2 pint lemon juice [10 ounces]1/2 pint orange juice [10 ounces]1/2 cup sugar4 sliced peaches1 sliced orangeabout 2 dozen halved strawberries or equal number raspberriesdiced pineapple3 pints soda water [60 ounces]

Mix sugar into wine in mixing bowl, add fruit juices, stir. Pour this over large lumps cracked ice in punch bowl. Add fruits. Just before serving add soda water. Fix slice of cucumber to rim of glass. Serves 24.

Jennifer Regan-Lefebvre is professor and chair of the history department at Trinity College, Connecticut. Find her on Instagram @jreganlefebvre.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.