Federal history programs must serve both the client agency and a larger public constituency. Such a dichotomy demands openness, accountability, and the highest standards of professionalism. Federal history offices engage in a variety of historical activities designed to support the mission of their agencies, educate and inform the general public, and provide scholars with new documentation. The Office of the Historian at the U.S. Department of State serves as a unique example of a historical program able to meet the demands placed upon it, especially in the area of public accountability.

Federal history programs must serve both the client agency and a larger public constituency. Such a dichotomy demands openness, accountability, and the highest standards of professionalism. Federal history offices engage in a variety of historical activities designed to support the mission of their agencies, educate and inform the general public, and provide scholars with new documentation. The Office of the Historian at the U.S. Department of State serves as a unique example of a historical program able to meet the demands placed upon it, especially in the area of public accountability.

The department's congressionally mandated Advisory Committee on Historical Diplomatic Documentation (commonly known as the Historical Advisory Committee or HAC), comprised of leading scholars, plays an important oversight role in the declassification and dissemination of the official foreign policy record. The relationship between the Office of the Historian and the Advisory Committee is a collaborative one, dedicated to a greater public and academic good.

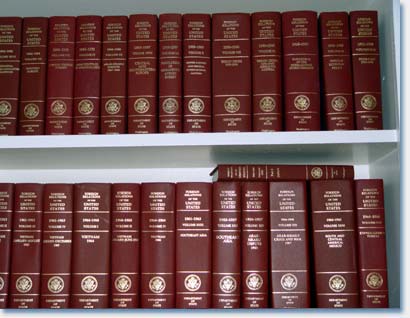

The Department of State has published theForeign Relations of the United States series (FRUS), the official historical record of diplomatic activity and foreign policy decisions, continuously since 1861. Initially known asPapers Relating to Foreign Affairs, the first volume in the series was published in December 1861 and contained Secretary of State William H. Seward’s instructions to American diplomats in London and Paris, as well as the Lincoln administration’s war aims. During the first 50 years of the series, State Department clerks selected and edited diplomatic correspondence for each year under the supervision of an assistant secretary of state. The first professionally trained historians charged with preparing Foreign Relations volumes joined the department in 1918. Secretary of State Frank B. Kellogg further professionalized the series by promulgating editorial standards forFRUS volumes, including document selection and editing, which exist to this day. The Department of State also expanded the number of volumes for each year, given the increasing global responsibilities the United States had assumed during the early 20th century.

Widening the scope of the Foreign Relations series necessitated the recruitment of additional historians. To that end, several professional organizations, including the American Historical Association (AHA) and the American Society for International Law (ASIL), lobbied Congress to increase the State Department’s publication program, asserting that they had the “responsibility to press the government for the release of information.”1 Congressional funding allowed the department to produce, during the 1940s and 1950s, not only the Foreign Relations series but also a variety of policy-supportive studies for Department principals.

Such lobbying efforts presaged a relationship between the professional organizations and the federal government and, importantly, between academic historians and public historians. Nowhere was this more evident than in the establishment of the Advisory Committee on Foreign Relations in 1956. During the early 1950s, the Republican leadership of the Senate requested that the Department of State publish the documentation of the Yalta and Potsdam conferences, and subsequently pressed for publication of the complete record of wartime conferences, stretching from 1941 to 1945. The Historical Division created a special research team in order to prioritize this assignment. In addition, the Department leadership tasked the Historical Division with the preparation of volumes detailing U.S.-China relations during the 1941–1949 period, in part, to provide a comprehensive record of U.S. decision-making. The fact that the wartime and China volumes developed in a politicized context, made evident by the department's premature release of the Yalta galley proofs to The New York Times in 1955, raised concerns among academics as to the methodology and integrity of the Foreign Relations series. The AHA, in response to members’ concerns, proposed that the organization’s Committee on the Historian and the Federal Government assist in the creation of an advisory committee, comprised of leading scholars in the history, political science, archival, and legal fields, to monitor the production of Foreign Relations volumes and press for timely declassification of federal diplomatic records.2

During the changing political climate of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Foreign Relations series served as a lightening rod for criticism of government secrecy. Tensions developed between those historians who conducted research in the field of diplomatic history and the federal agencies and employees responsible for maintenance and declassification of federal records. The Office of the Historian, plagued by staff attrition and retirement, became caught in the middle of the controversy. Executive Order 11652, issued by President Richard Nixon in March 1972, lessened the tension by mandating declassification of government records according to a prescribed schedule. By the mid 1970s, however, the series was more than 20 years behind currency. The gap would continue to widen throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Incomplete coverage of coups in Guatemala in 1954 (volume published in 1983) and Iran in 1953 (volume published in 1989) elicited a public outcry over the series. The Advisory Committee chair Warren Cohen resigned in protest. This public castigation of the series led Congress to establish a statutory requirement in the fall of 1991—the Foreign Relations Authorization Act (PL 102–138)—which required the Office of the Historian to publish a “thorough, accurate, and reliable record” of foreign policy and diplomatic activity 30 years after the events.

The concepts of transparency and openness as suggested by this mandate prompted Congress to establish the Advisory Committee on Historical Diplomatic Documentation, also known as the Historical Advisory Committee (HAC). Replacing the earlier committee, the HAC carries a congressional mandate to oversee the opening of diplomatic records in a timely and thorough fashion. The committee’s membership consists of nine members nominated by the AHA, the American Society of International Law, the American Political Science Association, the Organization of American Historians, the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations, and the Society of American Archivists. These historians, political scientists, archivists, and lawyers hold the necessary security clearances to enable them to examine documents and advocate for their release.

The committee convenes in two-day quarterly meetings to carry out its dual responsibilities: to ensure the preparation and timely publication of theForeign Relations series and to facilitate public access to Department of State records that are 25 years or older from the date of issue. The FRUS editorial review process spans from the conceptualization of the volumes to their delivery in print or electronic form. Committee members read documents in the compilation stage, advising on historical issues and the release of classified material under consideration. Even when aForeign Relations volume is completed, the committee reviews and critiques the volume to determine if it meets scholarly expectations. Regarding declassification, the scholars examine the Department of State’s guidelines for opening records and, by random sampling, peruse documents representative of all departmental materials still classified after 30 years. Most notably, the committee hears from a host of constituent agencies involved with the Foreign Relations process—the National Archives, the Library of Congress, presidential libraries, and executive branch departments—about their efforts to meet the 30-year rule. For instance, representatives of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) regularly report to the Committee. The committee also presses for timely and fair treatment of requests for declassification from all agencies, including the CIA, the Department of Defense, and the Department of the Treasury.

A certain tension is inherent between the Historian's Office and the Committee. Documentation must be comprehensive; but it must also be published within 30 years of the date of the original records. Under the provisions of Executive Order 12958 (as amended by the George W. Bush administration) documents older than 25 years must be declassified and made accessible to the public; records that might pose a risk to the security of the United States must remain classified. A directive from the White House after 9/11, and issues of control over former presidents' files, have slowed or prevented the release of key presidential papers, creating a delay in the release of certain documentation. The problem of meeting the Foreign Relation's series 30-year requirement is no less acute, and due to declassification delays, the series is currently behind schedule, and has been for some years. The committee's focus continues to be upon bringing the series into full compliance with the law, and progress is being made in that direction. A bright spot was the release in 2006 of 11 Foreign Relations volumes, the majority of which documented key events during the Richard M. Nixon and Gerald R. Ford administrations.

The committee's raison d'etre is to serve the public interest. Thus, one afternoon of each meeting is open to interested observers; participants have included the National Security Archive (NSA) and the National Coalition for History (NCH). The committee has also dealt with controversies, such as a formal protest in 2006 over the Bush administration's reclassification of documents. In addition, luncheons and special sessions involve guests ranging from senior administration officials (including Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Archivist of the United States Allen Weinstein) to historical organization representatives. Moreover, the committee performs its duty to the public by submitting a required annual report to the Secretary of State that sets forth its findings regarding both the progress and limitations of the editorial and declassification processes of the Foreign Relations series, as well as the declassification and opening of Department of State records. The watchdog committee, then, is designed to assure the Historian's Office, Congress, and the public that the declassification process and publication of the Foreign Relations series is on the right track toward greater transparency.

—Kristin L. Ahlberg is a historian in the Europe and Global Issues Division, Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State. She has published articles in Diplomatic History, the Organization of American Historians Newsletter, andThe Federalist. Ahlberg received her PhD from the University of Nebraska.

—Thomas W. Zeiler is professor of history at the University of Colorado-Boulder and a member of the Historical Advisory Committee. He is the executive editor of Diplomatic History and is a member of the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations (SHAFR) Council. His publications include: Ambassadors in Pinstripes: The Spalding World Baseball Tour and the Birth of the American Empire (Rowman and Littlefield) andAmerican Trade and Power in the 1960s (Columbia University Press). Zeiler received his PhD from the University of Massachusetts.

Notes

1. William Sheppard, “The Plight of ‘Foreign Relations’: A Plea for Action,” American Historical Association Newsletter, Vol. IX, No. 5, November 1971, 24.

2. The original members of the committee included: Thomas Bailey (Stanford Univ.); Clarence Berdahl (Univ. of Illinois); Leland Goodrich (Columbia Univ.); Richard Leopold (Northwestern Univ.); Dexter Perkins (Cornell Univ.); Philip Thayer (Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies); and Edgar Turlington (Washington, D.C. lawyer). See the “Report of the Advisory Committee on Foreign Relations to the Historical Division of the Department of State,” The American Journal of International Law, 52:3 (July 1958), 510. Leopold provides an excellent overview of the committee’s founding in “The Foreign Relations Series: A Centennial Estimate,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 49:4 (March 1963).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.