What with all the dispiriting talk lately about the use of history and history education as a political football, I thought I might share some good news: one aspect of the historian’s craft is in superb shape.

Book prizes are important markers of scholarly achievement, but how are they actually awarded? Coffee Channel/coffee-channel.com/CC BY 2.0

In 2022, I served as chair of the jury for the Cundill History Prize. An annual award administered by McGill University in Montreal and funded by a foundation formed by Canadian financier Peter Cundill, the prize is better known in Canada and the United Kingdom than in the United States. It is the richest in the world for history books: it carries a US$75,000 purse for the winner, and $10,000 for each of two runners-up. As a consequence, there is strong competition: in 2022, about 400 books were entered in the competition.

McGill history department faculty made the first cuts early in the year, eliminating many good books that for one reason or another they judged not quite good enough. I checked on a couple of their decisions and found I agreed. That left about 40 books for the committee to look at in the summer and fall, all of which, the McGill historians felt, met the formal criteria for the prize: books that were a joy to read, exhibited the best of the historian’s craft, and took on consequential subjects. Over several months, the jury read these works, and winnowed the list to 16, then to eight, to three, and finally to one winner. I learned—or relearned—a lot of things along the way.

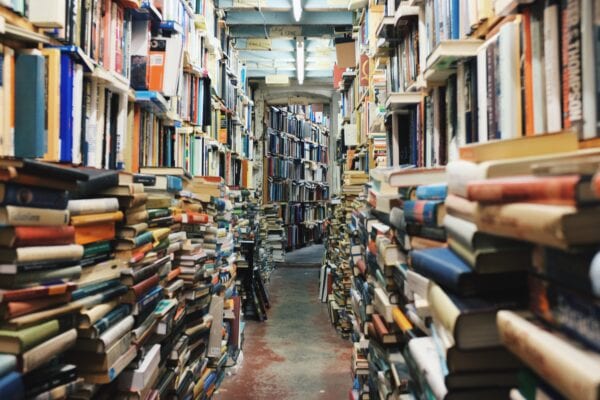

Perhaps the most important thing I had once known but sadly forgotten: how delightful it is to open a good history book without an urgent deadline. A large share of my reading is books I must finish hurriedly because I’ve assigned them for a looming class. For my research, like most everyone else, I almost never actually read an entire book; I merely forage for useful tidbits as fast as I can. For the Cundill Prize, however, I had to work my way through a waist-high stack of hardcover history books, pen in hand, usually in summer sunshine. I had to keep up a leisurely pace of roughly a book every four days. Life doesn’t get much better than that.

For my research, like most everyone else, I almost never actually read a book; I merely forage for useful tidbits as fast as I can.

The books included just about every variety of history. Even though I like to think of myself as a comparatively wide-ranging historian, in the normal course of events I don’t read much about domestic US history. Or Carthaginian history. Or the history of journalism. Some books were deeply archival, others more synoptic. Some told stories. Some answered questions analytically. For the Cundill Prize, I read books I would never have touched without my obligation as a jury member. Indeed, in most cases, I never would have even known these books existed. At most I might, a year or two after their publication, skim over their mentions in the review section of the American Historical Review and silently say to myself there’s no grist for my mills there. While I suspect there will be no practical value for me in learning a little about the history of, say, journalism, I feel glad to have done so. And who knows what might turn out to be practical to know at least a little about in the future?

Precisely because the books varied so much in subject and method, the jury’s decisions were especially hard. Most book prizes involve judging works that have something fundamental in common, such as studies of Italian history or East Asian history since 1800. All the AHA book prizes are limited in some way, although a few are pretty broad (e.g., the Breasted Prize for a book on any subject before 1000 CE or the Beveridge Award for a book on any aspect of the history of the American hemisphere). These no doubt pose stiff challenges for the juries involved. Still, the great majority of books are ineligible for these AHA prizes while every history book is eligible for the Cundill Prize. We were comparing apples not only to oranges, but to mangos, rambutans, eggs, and crabs.

This omnivorous quality of the work might paradoxically have made the jury’s task easier in one sense. Often juries struggle to reach consensus and discussions yield contention, even rancor. This jury did not have those struggles. Maybe I was just lucky with my jury colleagues, but I think something else might have been at work too. Part of the reason consensus eludes many juries is that they are selected, sensibly enough, for their expertise in the area of the prize they are to judge. When I helped to judge an environmental history book prize, I felt more confident in my powers of discernment because I had spent long years trying to educate myself in that field. That made it more tempting to trust my own preferences and preconceptions. My colleagues, on that occasion, seemed to feel the same way about theirs.

We were comparing apples not only to oranges, but to mangos, rambutans, eggs, and crabs

On the Cundill jury, I had colleagues who knew vastly more than I ever will about big swatches of history and historiography. With many books, it felt easy to defer to their judgment and abandon my own, in a way that it might not had I been operating within my comfort zone. I suspect they felt the same way, because our several Zoom discussions were long on respectful deference and mercifully short on stubborn insistence.

The most important thing I learned is the astounding brilliance that so many of my fellow historians bring to important topics. Since I became a historian, I have often been reminded that our profession has many imperfections. I sometimes get discouraged about its future. And lately—like the AHA—I’ve worried about the weaponization of history in political culture wars. But reading dozens of books about topics I normally ignore, written by historians who in most cases I had not previously heard of, amplified my faith in the value of what historians do, the value of the variety of what they do—and the skill with which they do it.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.