In recent years, while working toward my PhD in history at Cornell University, I’ve taught several college history courses in maximum and medium security men’s prisons across upstate New York. For me and many other instructors, the prison classroom is a remarkable, inspiring, often fun space for intellectual inquiry and mutual learning. But we also face unspoken and unforeseen barriers when it comes to mentorship, relationship building, and offering emotional and academic support to our students.

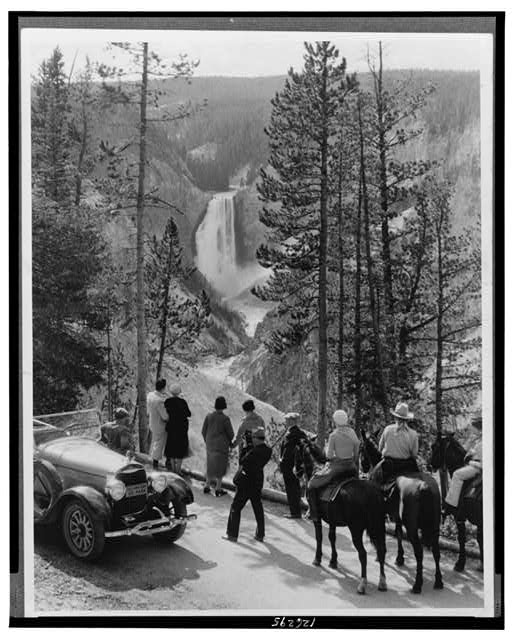

To ignore the structural differences between teaching in prison versus other college settings leads to potential blind spots that can limit the capacity of instructors to understand and serve our students. National Archives and Records Administration, Identifier 299557

Instructors often hear that college classes serve as an escape from the daily brutality of prison life; the flip side is that instructors are largely shielded from these realities. Instructors are encouraged not to prejudge incarcerated students, personally or academically. Many of us feel that our student’s histories, specifically their pathways to prison, should become irrelevant when they walk into our judgment-free classrooms. But as much as the illusion of the context-free classroom liberates us to engage in deep intellectual inquiry alongside our students, these structural and unspoken constraints also limit our ability to know them and their stories. For institutional reasons, students tend to keep legal hardships and personal tragedies out of our classrooms. As a consequence, we often never learn why strong students suddenly begin struggling to stay focused or stop turning in work. When students disappear from class altogether, we rarely get explanations and never get goodbyes.

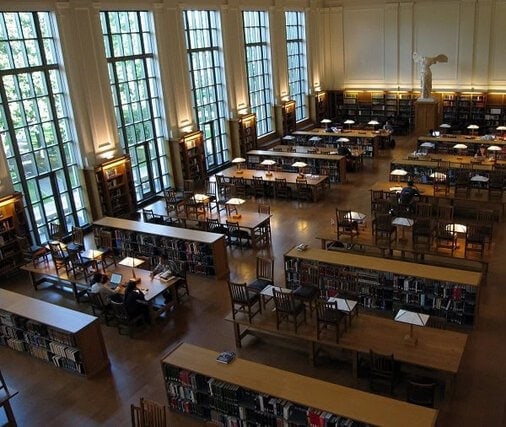

There are also logistical challenges. There is no online submission of work or feedback, no internet access for student research. At the prisons in which I’ve taught, most assignments are written by hand, and research is restricted to course texts and the prison’s limited library. There are no office hours in prison, and few opportunities to discuss students’ learning one-on-one. Periodic lockdowns can mean missing weeks of class with no opportunity to communicate with students. Writing resources that many college educators take for granted, from spellcheck to campus writing centers, are not available to most incarcerated students. And there are all the security-driven institutional imperatives that shape the experience of teaching in prison. Some facilities allow handshakes between students and instructors and the use of students’ first names, but some do not. Instructors can be banned from teaching with the Department of Corrections for writing letters to former students or distributing end-of-the-year notes with well wishes. More often, it is the students who are disciplined for perceived transgressions or impropriety. In this charged environment, historians must also think carefully about the readings they assign, all of which are subject to review by prison administrators. Historian Margaret Garb, who passed away in 2018, wrote eloquently about these issues in the context of teaching US history to incarcerated students in the months following the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson. Topics like slave rebellions or civil rights can be touchy subjects within the prison’s walls.

I cannot overstate the value of the conversations and connections made in these classes.

Despite these constraints, I cannot overstate the value of the conversations and connections made in these classes. Trying to prompt discussion in a silent room of downturned heads is not a problem in the prison classroom. I have never met with students who read so closely, show such passion for our material, and think so creatively. Our discussions are wide-ranging and reflect deep intellectual curiosity about daily life for working people in the 19th-century US, the logic behind military decisions during the Civil War, and definitions of art and kitsch. In my environmental history courses, we never escape the question, “but what is nature?” My students and I also talk about why history matters, about the nature of historical change, about whose version of history gets privileged. We discuss what constitutes a canon, why we trust particular sources, and why so much of history feels like a conversation that’s only taking place among historians.

As my students remind me to ask what writing and researching history looks like, and whom it’s meant for, they shake up the bubble I inhabit as a white graduate student at an elite university. In an effort to overcome some of the structural limitations of teaching in prison, and to open up the classroom to more voices, I’ve had my students write to the scholars whose work we have read together to ask about the methodology, intellectual questions, and writing challenges that underpin professional historical scholarship. When possible, I’ve invited practicing historians into our classroom to give guest lectures and engage with students. In planning future courses, I’m inspired by colleagues who have students on campus exchange papers with incarcerated students and collaborate on research projects. It is an exciting moment for prison education nationally; such cross-campus relationships seem to be growing in popularity, and the inside-out model of prison teaching has been successful in many communities.

The energy of my classes inside has given me a fearlessness and enthusiasm for teaching in all contexts.

The energy of my classes inside has given me a fearlessness and enthusiasm for teaching in all contexts. I strive to show all of my students respect, listen to their voices, and take seriously a practice of “co-immersion with students in the production of ideas.”1 Yet, as I engage more deeply in this work and the broader context of mass incarceration in the US, I grow more cognizant of the tensions and contradictions in how we know and relate to our students and I am grateful for the robust conversations taking place between students, instructors, and advocates about prison pedagogy. In an open letter to prison educators, a student recently summed up some of these conversations with a succinct reminder: “It’s not about you.”2 This lesson is a helpful check for all educators, but has special meaning for prison instructors, who can easily fall into the trap of believing it is their task totransform and liberate their students. In my experience, being mindful that “it’s not about me” means initiating conversations with my students about what pedagogical practice should look like and frankly acknowledging my failures as well as successes in the classroom.

To ignore the structural differences between teaching in prison versus other college settings leads to potential blind spots that can limit the capacity of instructors to understand and serve our students. To embrace the complexities of teaching in this environment, in contrast, is hard, humbling, and profoundly educational.

Molly Reed is a PhD candidate in history at Cornell University. She has been teaching college courses in environmental history and United States history in New York state prisons since 2014.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.