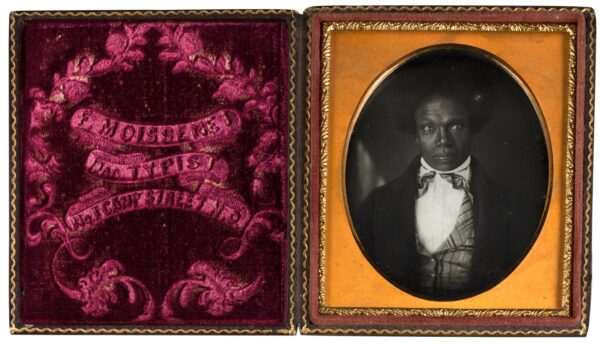

In an age when most photographs we take never physically exist, it is easy to forget that photography originated as a visual and tactile medium. It is exactly this material nature that makes Portrait of a Man (ca. 1852) one of my favorite photographs in the New Orleans Museum of Art’s collection. Touched by the hands of both the photographer, Felix Moissenet, and the unidentified Black man who sat for it, this daguerreotype invites us to explore the important history of how people of African descent participated in New Orleans’s early photography scene.

Felix Moissenet, Portrait of a Man, ca. 1852. Daguerreotype, 3¼ × 2¾ inches. New Orleans Museum of Art, Museum Purchase, Maya and James Brace Fund, 2013.22.

Introduced to New Orleans in 1840, daguerreotypes made portraiture widely available for the first time. Louis Daguerre’s process used light-sensitive chemistry to record an image on a polished sheet of silver-plated copper. Requiring no negative, every daguerreotype was one of a kind. By the 1850s, an exposure of several seconds produced an incredibly detailed portrait. (With magnification, you can see Moissenet’s reflection in the sitter’s eyes!) Daguerreotypists covered each finished plate with glass to protect its fragile surface and often placed it in a book-like case that made the daguerreotype safely portable, exchangeable, and easier to view. By closing the cover slightly and looking at the picture from an angle, a viewer can minimize reflections on the mirrored plate and focus on the image itself. Viewing a cased daguerreotype was, and remains, an intimate experience engaging both touch and sight.

This case’s velvet lining bears the imprint of daguerreotypist Felix Moissenet, the sole proprietor between 1851 and 1855 at No. 1 Camp Street—just steps from the site of the 2022 AHA annual meeting. Born in France around 1814, Moissenet was a white photographer active in New Orleans between 1849 and 1861, when the intersection of Canal and Camp Streets was the city’s photography epicenter. Competition was fierce; Moissenet advertised his “super excellent daguerreotype portraits,” promising “results that have been sought in vain by other operators.”

Black people likely made up a sizable portion of Moissenet’s clientele. More broadly, in the 19th century, Black Americans, including famous figures like Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth and countless people whose names have been obscured, explored photography’s potential for self-definition. Photographs were assuredly part of the daily lives of the 10,000 free people of color living in New Orleans, many of whom owned real estate, operated businesses, and formed collective institutions. Enslaved people, also, as scholarship by Matthew Fox-Amato has established, purchased their own photographs, openly or clandestinely, across the American South.

We do not yet know the identity of the man in this portrait and can only speculate about how he felt about his photograph. The quarter-length pose, his dress, and the assertive way this man meets the camera’s gaze suggest he commissioned his own portrait. As bell hooks, Deborah Willis, and others have shown, photography offered Black people a tool to practically and psychologically navigate the white supremacist social order. For this man, sitting for a photograph was both a personal and a political act, an irrefutable assertion of personhood when so much of America’s visual culture distorted or denied his existence. This photograph may be the best record we have of his life, and it exists because he chose to step in front of the camera and represent himself. The singular nature of a daguerreotype means that this is the very object he used to do so, and then he passed it into the future. That a photograph you can hold in the palm of your hand can carry that kind of historical gravity is a remarkable thing.

Brian Piper is the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Assistant Curator of Photographs at the New Orleans Museum of Art and a member of the 2022 annual meeting local arrangements committee. He is on Instagram @nomaphotographs.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.