Phillip Lapsansky, the longtime chief of reference and curator of African American history at the Library Company of Philadelphia, died on April 9, 2024, in Philadelphia. For generations of scholars, Phil was more than a librarian; he was an essential resource whose efforts in building the African Americana Collection offered critical insights on Black protest, reform, and writing before the 20th century.

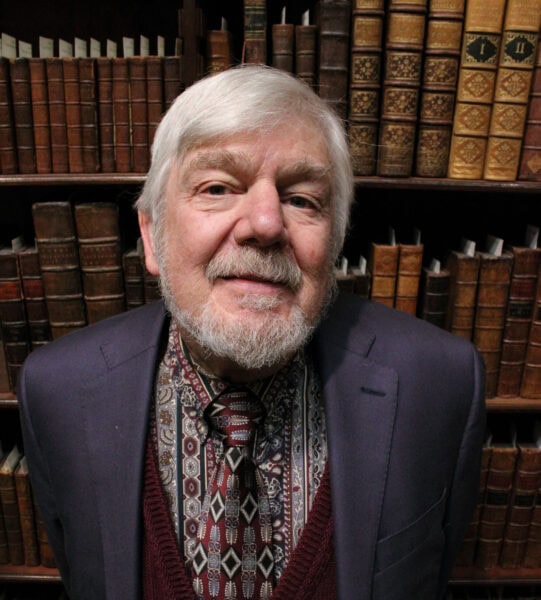

Courtesy Library Company of Philadelphia

Born in Seattle, Phil briefly attended the University of Washington, where he participated in labor and political struggles. After sojourns at home and abroad, he went to Mississippi in 1964 to join the Civil Rights Movement. He ran the Freedom Information Service and wrote about his experiences for national publications (he was proud to have an FBI file). In Mississippi, he met activist and historian Emma Jones; they married in 1966—though they wed in Wisconsin because Mississippi banned interracial marriage. They had three children, Jordan, Jeannette, and Charlotte, before divorcing. After many years together, Phil married Bernice Andrews in 2012.

Phil took a job at the Library Company in 1971 and resumed his studies at Temple University (BA, 1973). Hired to identify and catalog the voluminous collections of African and African American materials in both the Library Company and the neighboring Historical Society of Pennsylvania, he hit the stacks with what became his signature combination of passion, discernment, and commitment. Realizing that African American history was a burgeoning field, Phil and the Library Company published a massive reference volume, Afro-Americana, 1553–1906: Author Catalog of the Library Company of Philadelphia and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (1973). Phil ensured that the Library Company remained at the forefront of archiving and disseminating material on the Black experience. The Library Company eventually created a Program in African American History, including lectures, internships, and fellowships. In many ways, it all rested on Phil’s exhaustive archival work and knowledge of the field.

For nearly 40 years, Phil delighted in showing historians his accordion-like folders relating to new material in the archives. He paid close attention to academic trends so that he could acquire materials relating to new areas of inquiry, such as print culture, Caribbean protest, and visual culture. Phil was responsible for acquiring 2,500 new items for the African Americana Collection (which eventually grew to over 13,000 items). In 2008, the Library Company published a revised edition of the African Americana catalog, which remains a key resource for scholars around the world. Phil also wrote articles, co-edited the important Pamphlets of Protest: An Anthology of Early African American Protest Literature, 1790–1860 (2001), and curated significant exhibitions on subjects as varied as political cartoons and antislavery women.

But no matter how large the collection grew, every document mattered to Phil, and he shared his enthusiasm with others. For example, he kept in his wallet a small photocopy of a document acquired in the early 2000s: a series of devotional lines from the Qur’an written down in Arabic by an enslaved person in the French colony of Saint-Domingue and collected by a curious Swiss visitor in 1773. For Phil, it was a testament to human resilience and a reminder that archives could indeed uncover lost stories from the past. When Phil showed the original document to scholar Laurent Dubois, he was inspired to research Islamic survivals in the Americas. “I learned that day what so many others have known,” Dubois later wrote, “that Phil seamlessly combined his roles as researcher, curator, and host and was a font of endless generosity and curiosity.”

As the publication of a festschrift at his retirement in 2012 showed, many scholars agreed with this assessment. Entitled Phil Lapsansky: Appreciations, the volume—available online—included reminiscences from 50 scholars praising Phil’s impact on their work. According to Library Company director John C. Van Horne, the book illustrated the “universally high regard in which Phil is held.”

Appropriately for a curator at a library launched by Benjamin Franklin, Phil was delightfully mischievous, a bit of a bon vivant, and ever curious about the world beyond the archive. Yet he believed deeply in the power of knowledge to change society and saw the past (especially the liberation struggles of oppressed people) as a pathway to creating a more just future. He will be missed but remembered every time someone calls out material from the African Americana Collection.

Randall M. Miller

Saint Joseph’s University

Richard S. Newman

Rochester Institute of Technology

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.