In the 16th century, a Capuchin monk confidently wrote, “There are some men who have never seen, or perhaps could never see a ghost; there are others to whose lot it falls to have many such supernatural experiences.” Almost 500 years after the appearance of this Treatise on Ghosts, otherworldly spirits are welcome apparitions in course catalogs and syllabi. The distant past can often appear to students as unknowable because of its strangeness, and the mysteries of ghosts offer an accessible way into this strangeness. Their ubiquity in pop culture means that, frightening as they may be in context, the undead are refreshingly free of intimidation for students. These otherworldly apparitions provide a case study in learning about and through unfamiliar cultural beliefs.

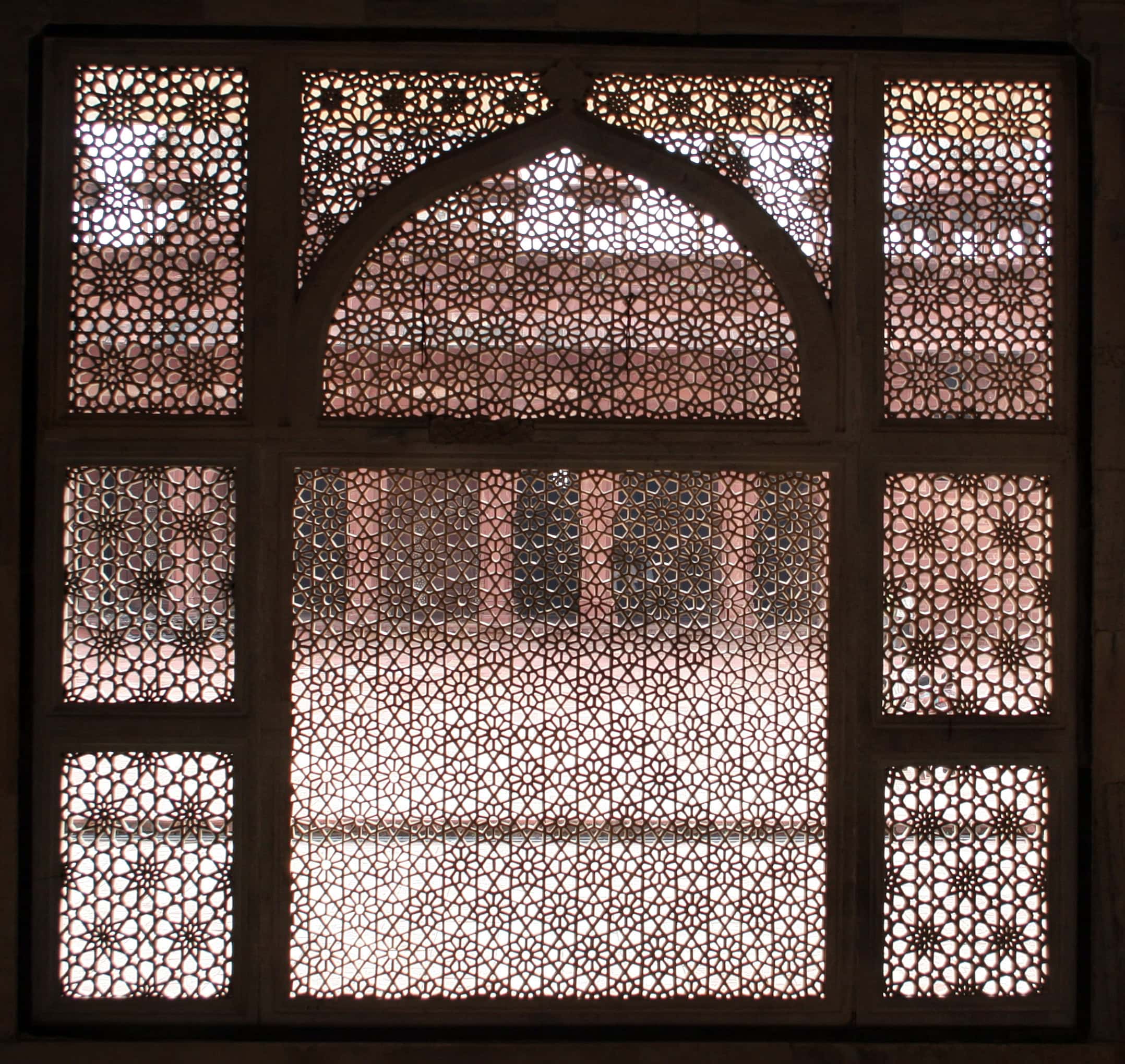

Ghosts captivate the attention of learners while providing a fertile source base for comparative teaching. Four Bricks Tall/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Ghosts and revenants and spectral visions have appeared in conversations not only about the living and the dead but also about identity, gender, sexuality, and more. And for the period I teach, from late antiquity to early modernity, I have found that these unquiet dead can, like the spirit who took Ebenezer Scrooge by the hand in A Christmas Carol, serve as helpful guides in both literature and history courses. Studying ghosts requires constant engagement with a question central to the study of history itself: How do the living relate to the dead? Discovering how texts from different times and places answer this question allows students to explore complex realities.

Looking at the living and the dead is a convenient—and, in my experience, attractive—way of sharpening the focus of an introductory course. Moreover, this approach showcases a wide range of beliefs about what the underworld was like and how it was accessed, as well as what it might mean for the dead to speak to the living. To structure one of my courses on the history of medieval European literature, I used The Penguin Book of the Undead: Fifteen Hundred Years of Supernatural Encounters (2016), edited by Scott G. Bruce. This volume contains a variety of texts from Homer to Hamlet, via revenants in French abbeys and on Viking farmsteads, introducing students to the wide diversity of traditions in medieval Europe. Through ghosts, students can see the diversity of thought and belief in the Middle Ages and begin to unpick myths of a monolithic medieval period.

My course begins with the diversity of traditions circulating in medieval Europe and influencing medieval Christian authors in order to debunk the stereotype of medieval Europe as a stagnant and isolated time and place, inheriting and adapting nothing. Moreover, having students read biblical passages about Saul and the witch of Endor, the Homeric story of Odysseus and Elphenor, and the autobiographical text of the third-century North African martyr Perpetua offers them ways into thinking about what the dead—and the undead—can tell us about the lives of historical actors.

Through ghosts, students can see the diversity of thought and belief in the Middle Ages and begin to unpick myths of a monolithic medieval period.

When Saul, incognito, seeks insight from the witch (or, less pejoratively, prophetess) of Endor, he is terrified both by the apparition of the dead prophet Samuel, who foretells his death, and by the woman’s recognition of him as the king of Israel despite his disguise. In such stories, the dead often have the power to tell the future; this particular episode also raises the question of how morality affects death, life, and the afterlife. Does Samuel respond to the power of the woman who calls him? Or does he appear in order to admonish the king, ignoring the woman of Endor as an alternate source of spiritual authority? Similarly, in Homer’s epic, Odysseus’s encounter with Elphenor shows us ancient spaces devoted to the afterlife, and the difficulty of communication between the living and the dead. And in third-century Carthage, Perpetua’s vision of her dead brother Dinocrates and her conviction that her prayers could relieve his suffering provide one of the earliest testimonies to developing Christian beliefs about the afterlife and prayers for the dead. These vivid visions, including that of her brother, offer insight into the developing conceptual lexicon of Christianity. Further, Perpetua had a strong sense of her own identity as part of a community of Christians, and of the challenges this posed to her identity as a Roman matron, all of which are accentuated by the fact that the text is autobiographical. To consider the implications of her authorship is also to consider the social history of religion.

Beyond these ancient precedents, the discernment of saints and the uncertainty of churchmen and theologians with regard to the undead in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages allows students to see medieval Christianity as something evolving, dynamic, and hybrid: it was neither Monty Python’s Inquisition nor Protestantism’s memory of an Orwellian superstructure designed to monitor thought and control belief. By the time we reach Shakespeare’s Hamlet at the end of the course, students are prepared to see how Horatio’s scholarship equips him to speak to the ghost of Hamlet’s father, and why the frightened courtiers and soldiers expect that the royal Dane might have foreknowledge of the future.

When using ghost stories, I’ve taken a variety of approaches in the classroom. A class period that falls on Halloween is an opportunity for “ghost day.” Toward the end of the fall semester, an excuse to engage goodwill and humor is always welcome. And pairing translations of ghost stories from Byland Abbey’s chronicle by M. R. James, an early 20th-century medievalist, with one of James’s own stories (I’m particularly fond of “The Treasure of Abbot Thomas”) can be a great way of talking about popular reception of the Middle Ages in Victorian England and beyond. Ghost stories are flexible: these same medieval sources can be deployed in discussions of monastic culture and identity, and monasteries’ many social functions. Their theological sophistication allows my class to talk about the implications of how many of the surviving texts from medieval Europe were created inside monasteries. The documentary culture that we look at is more male, more Christian, and more educated than many members of the societies from which those texts came. Bishop Thietmar of Merseburg’s (d. 1018) priest-burning revenants, for example, illustrate doctrinal debate, dissent, and religious hybridity. Particularly if paired with a relevant podcast episode, these graphic and engaging stories can be used to model practices of close reading and analysis. What does it mean for an 11th-century German bishop to include such violent stories in his political chronicle? What does it mean for him to present these stories as, if not definitely substantiated, at least plausible? Class discussion can also be kick-started by a lively debate on whether or not we can call these revenants zombies.

Medieval ghost stories like those in the Book of the Undead can also be paired with non-European primary sources in global history courses, with productive comparisons being drawn among narrative conventions of ghost stories. Mysterious dreams experienced by Carolingian emperors can be paired with the prophetic dreams experienced by government officials in Song China and chronicled in Hong Mai’s Tales of the Listener. The porous boundaries between this world and others in early medieval Europe are also found in the stories collected in African Myths of Origin. And discussing the use of ghosts to deal with collective trauma can be done with a discussion of violence in high medieval France and late Heian Japan. “The Story of Mimi-Nashi-Hôïchi,” collected by Lafcadio and Setsu Hearn, recounts the travails of a blind biwa player whose skill results in ghosts demanding that he tell them their own story. Mimi-Nashi-Hôïchi’s ability to evoke the desperation and pathos of the Genpei War was, readers are told, unequaled. The ghosts, weeping over their own fates, are assured of the compassion of the living but are—like many of the undead—violent and unpredictable in their desires.

One of my favorite selections to teach with is an anecdote recounted by the 11th-century monk and theologian Peter Damian with the sensational title of “A Lesbian Ghost.” I confess that when I first saw the title in the table of contents, I momentarily suspected editorial simplification, if not exaggeration, for dramatic effect. But no: in this story, a deceased nun appears to her goddaughter, both to foretell the future and to admonish the girl about the desirability of frequent and conscientious confession. The latter is illustrated through the fact that the nun herself forgot, before dying, to be shriven of “wanton lust with girls of her own age.” She has the power to appear from heaven, nevertheless, because of the mercy of the Virgin Mary, who reminded her of this forgotten sin.

Exploring the richer and more nuanced realities of what the story demonstrates provides a way of exploring the complexity of the medieval past.

On a first reading, students are usually convinced that this story demonstrates that the Medieval Church (capital letters definitely implied) disapproved strongly of nonheteronormative sexual behaviors and identities. Exploring, then, the richer and more nuanced realities of what it does demonstrate provides a way of exploring the complexity of the medieval past. Reading about a lesbian ghost emphasizing the importance of confession, devotion to the Virgin Mary, and the reach of divine grace is a far easier entry point into the reform movement of the 11th-century church of which Damian was part than theological treatises or a discussion of the investiture controversy. When we read The Divine Comedy, students can see how other readers responded to the same author when they find Peter Damian welcoming Dante to the seventh circle of paradise.

I’ve focused on primarily medieval examples, but ghostly apparitions do similar work across multiple time periods and geographies. One of their most important roles is to help students see that history includes what past societies believed, as well as the verifiable facts of what happened. Letting ghosts do the talking, as suggested by Robertson Davies, can be an effective way of eliciting student curiosity and building students’ knowledge. As the living encounter the undead, so do we encounter the otherness and the immediacy of historical authors and actors.

Lucy Barnhouse is an assistant professor at Arkansas State University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.