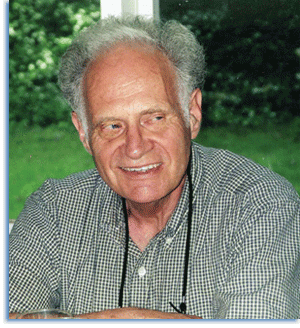

Peter H. Amann. Credit: Paula Amann

The eminent historian of France, Peter H. Amann, who died June 14, 2012, lived a full and remarkable life. Born in Vienna on May 31, 1927, his father, the German intellectual Paul Amann, was an author, translator, notable correspondent, and professor at a Gymnasium in Vienna from 1911 to 1938. In 1924, he married Dora Iranyi, a concert singer, and the couple had two children, Peter Heinrich, the eldest, and Eva.

Because of his Jewish ancestry, Amann’s father’s books were banned in Nazi Germany in 1935, and, after the Anschluss in 1938, the family became victims of Nazi persecution. As their situation deteriorated, the Amann family fled Vienna in 1939, which enabled them to survive the coming Holocaust. Most of their relatives-including 14 grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins who remained behind in Austria-did not.

Immigrating first to Paris and then briefly with his sister to Bern, Switzerland, after the German invasion began in 1940, Peter and his family were reunited near the Atlantic coast as French resistance collapsed. They made their way toward the unoccupied south, living for a time in Montpellier before being befriended by the local Quaker relief organization in Marseilles, which obtained American refugee status for them and helped subsidize the cost of their voyage overseas. The Amanns made their way to Lisbon before boarding the ship for the passage to New York, where they arrived safe but nearly penniless in 1941.

After his family made the difficult initial adjustment to life in the United States, Peter enrolled at Oberlin College in Ohio, where he received a BA with honors in economics in 1947. There he met his future wife of 55 years, Enne Niemi Amann, who was a vocal music major from an Ohio Finnish immigrant family. After graduation, the Amanns lived in New York and Milwaukee, working as a machinist and writing fiction, before attending graduate school in history at the University of Chicago. He completed his MA in1953 and was awarded his PhD in 1958.

Amann worked as an instructor in history at Bowdoin College from 1956 to 1959 before joining the faculty at Oakland University in Michigan, where he served as an assistant and associate professor from 1959 to 1965. He then went to State University of New York-Binghamton before accepting an appointment as professor of history at the University of Michigan-Dearborn in 1968, where he taught until his retirement in 1992.

Amann’s scholarly interests were far ranging and multifaceted. Primarily a social historian of modern France who explored questions of revolutionary transformation “from below,” his earliest books focused on the 18th century. These included an edited volume, The Eighteenth Century Revolution: French or Western? (Heath, 1963), and a textbook, The Modern World: 1650-1850 (McGraw Hill, 1967). Amann’s Revolution and Mass Democracy: The Paris Club Movement in 1848 (Princeton Univ. Press, 1975) was perhaps his most influential work. Like other contemporary scholars of French crowd studies, including George Rudé, Albert Soboul, and Charles and Louis Tilly, Amann based his work on a mastery of the archival records in assessing more than 200 popular societies (enrolling perhaps 70,000 participants) that proliferated in Paris during the spring of 1848. In so doing, he was able to present the first detailed analysis of the internal composition and dynamics of the club movement and, hence, a much fuller understanding about this crucial aspect of the social and political history of the revolution.

A subsequent book, The Corncribs of Buzet: Modernizing Agriculture in the French Southwest (Princeton Univ. Press, 1990), explored the “silent revolution” in French agriculture that took place in the southwest after the Second World War. Basing his study on five villages in the department of HauteGaronne near Toulouse and adding oral histories to research in the archives, he assessed how subsistence peasants sought to transform themselves into market-oriented farmers. Amann’s final major work, The French Revolution at the Grassroots: A Critical Bibliography of Recent Works on Village, Small Towns, and Small Rural Regions during the Revolutionary Period (Univ. of Michigan Library, Scholarly Pub. Office, 2006), embraced a still-marginalized academic publishing medium-the Internet. Intended as a “service to the history profession” and coinciding roughly with the bicentennial, the bilingual critical bibliography Amann compiled encompassed all publications issued between 1980 and 1995 focusing on the local history of the Revolution of 1789.

Amann published articles in English and in French in major professional journals, including the American Historical Review, Journal of Modern History, French Historical Studies, International Review of Social History, Comparative Studies in History and Society, Revue d’histoire de la Deuxième Guerre Mondiale, European Historical Quarterly, and the New England Quarterly. His eclectic research interests produced several articles in the 1980s on the Black Legion, a Depression-era Detroitbased American proto-fascist movement. He also collaborated with his wife, Enne, in translating into English Jeanne Bisilliat and Michele Fieloux’s Women of the Third World: Work and Daily Life (Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, 1987).

The great merit of Amman’s scholarship was well recognized. He served as a member of the editorial board of the French Historical Society and was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1963. His commitment to scholarship was balanced by an equal commitment to liberal undergraduate education. He was honored with the University of Michigan-Dearborn’s Distinguished Teaching Award in 1975, and was the first recipient of the William E. Stirton Professorship from 1979 to 1984, the most prestigious award the university bestows on its faculty.

After his wife Enne’s death in 2003, Amann married Jean Apperson, a psychologist who shared his passion for France and nature, in 2004. In addition to completing his critical bibliography of the French Revolution while in retirement, he occupied himself with ornithology and carpentry, as well as his lifelong enthusiasm for mushroom foraging.

He was “loved by many people because of his special way of being” and, as his wife Jean remembered, for “his ingenuous charm.” In his later years, he was fond of using the French expression “fin de vie heureuse” and characterized his life near its end as having been “satisfactory”-a typically wry understatement. In addition to his wife Jean, Peter Amann is survived by his sister, Eva Amann Irrera; his children Paula, Sandra, and David; and three grandchildren.

Joe Lunn

University of Michigan-Dearborn