This essay is part of “What Is Scholarship Today?”

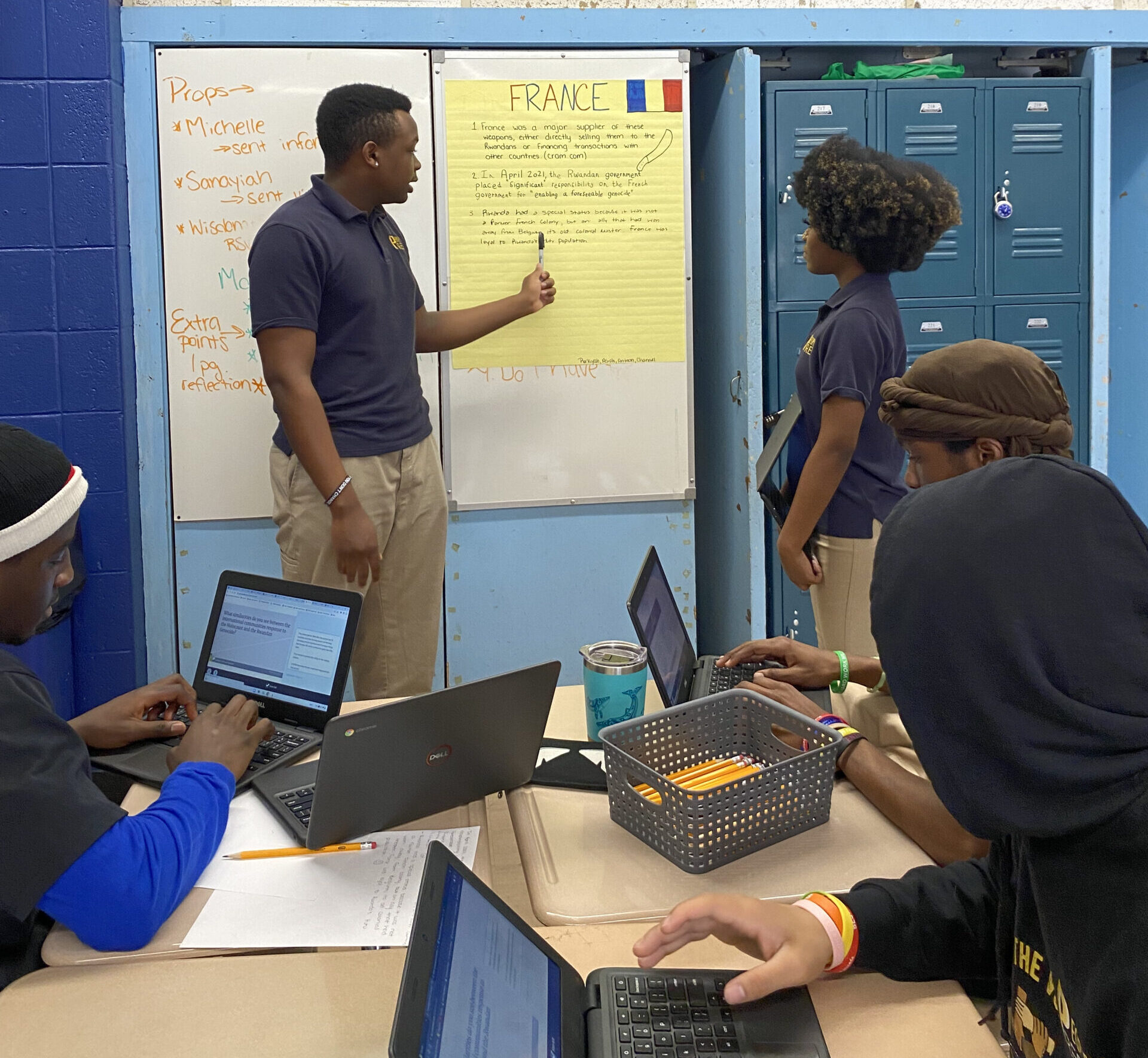

We are in a moment of great uncertainty. National and global developments force us, as historians, to think critically and creatively about the kind of work we want to produce, and just as significantly, we must carefully consider the mediums we will use.

Perhaps it’s my personal background as a first-generation college student that drives my deep concern about accessibility. As a graduate student, I made a vow never to publish anything that my mother could not read and understand. If my work could resonate with someone with limited formal education (and a marginal interest in history), then I knew that it would be meaningful indeed.

I can’t say for certain that I’ve always succeeded, but I do know that writing op-eds and blog posts has brought me much closer to my goal. Those pieces—and the ideas within them—have traveled to places I’ve never been and landed in the hands of people I could not otherwise reach.

I made a vow never to publish anything that my mother could not read and understand.

While we should not romanticize public writing—the brief word count runs counter to the historian’s preference for nuance—op-ed writing can be a powerful form of historical scholarship. The academic books and articles I have produced would have little reach were it not for how public writing has brought diverse audiences, far beyond the ivory tower, to my work.

This is not a trivial matter in a world rife with disinformation and misinformation. Writing op-eds based on scholarly research—and incorporating archival research—is one effective way that historians can challenge and refute how misconceptions about the past, deliberate or otherwise, inform some of the most pressing topics of the day. As a discipline, we should recognize how contributing to the public debate is as valuable as the work we do in classrooms, at academic conferences, and in academic journals. And it extends our voice beyond those who share our interests and professional training.

What is historical scholarship if not the production of new knowledge that can enrich our individual and collective lives while deepening our understanding of each other? Op-eds and other short writings can serve this function just as well as books and journal articles.

An op-ed may not require as much time as longer forms of writing, but it can better respond to a moment. In 2020, as a wave of protests against state-sanctioned violence erupted around the world, I drew on my research on Black women’s transnational activism to contextualize contemporary developments in a series of op-eds. Some of these articles have been cited in law journals, have influenced policy organizations and think tanks, and have been used to develop content for museum exhibits. The accessibility of the op-ed—its style, length, structure, and, in many cases, existence on the free internet (without a subscription)—made this possible.

While some may dismiss the op-ed as scholarship, skeptics should recognize that it often represents the beginning, not the end, of deep scholarly engagement. Writing op-eds has sparked my production of journal articles and books—those projects favored by tenure and promotion committees. My book on Fannie Lou Hamer is a case in point. Until I Am Free began as an op-ed for Time magazine, and I had no intention of writing a book at the time. But the article opened a public dialogue that led to a presidential candidate sharing it on social media, and it even caught the eye of a relative of Hamer who then reached out to me. The conversations the op-ed inspired helped me realize that it was only the beginning. And it blossomed into a book project.

These experiences underscore the need to view historical scholarship in expansive ways. It takes on various forms. Each form serves unique—yet deeply intertwined—functions. Though short in its form, the op-ed is a powerful tool for historians to sharpen their ideas and engage the broader public. As the publishing industry and the discipline evolve, we must open our minds to recognize the value of op-eds, podcasts, blogs, video essays, and other forms of historical scholarship. They each have a role to play—especially in these challenging times.

Keisha N. Blain is professor of Africana studies and history at Brown University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.