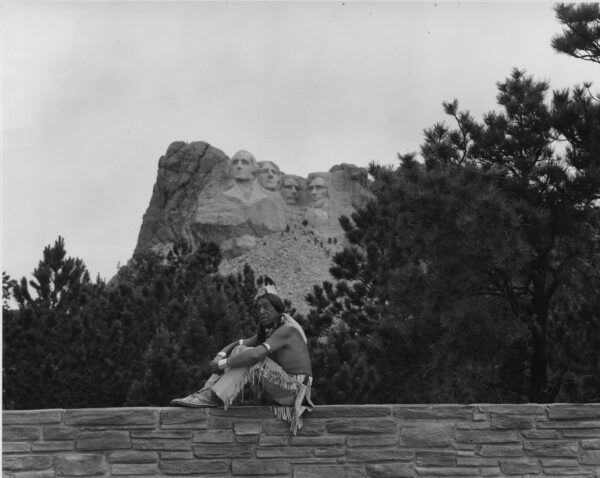

On July 4, 1939, at the base of a mountain in the Black Hills of South Dakota, a crowd gathered to watch a play. Actors dressed as explorers, miners, soldiers, and Native Americans enacted the history of the Black Hills, from the explorations of the French Vérendrye brothers in the early 18th century through the American settlement of the region in the late 19th century. The play concluded with actors playing the Lakota leaders Maȟpíya Lúta (Red Cloud) and Siŋté Glešká (Spotted Tail) on stage. “Let us not battle too fiercely,” suggested Maȟpíya Lúta, because “the Red Man no longer holds this land alone.” Siŋté Glešká agreed. “This strange White Man . . . is so flourishing there must be virtue and truth to his philosophy,” he said. He proclaimed that “Red man is old. He looks to young white master,” before exiting the stage, making way for miners chanting, “Gold in the Black Hills!” High above, four monumental presidential faces gazed down upon the scene playing out below, at the foot of the near-complete monument at Mount Rushmore.

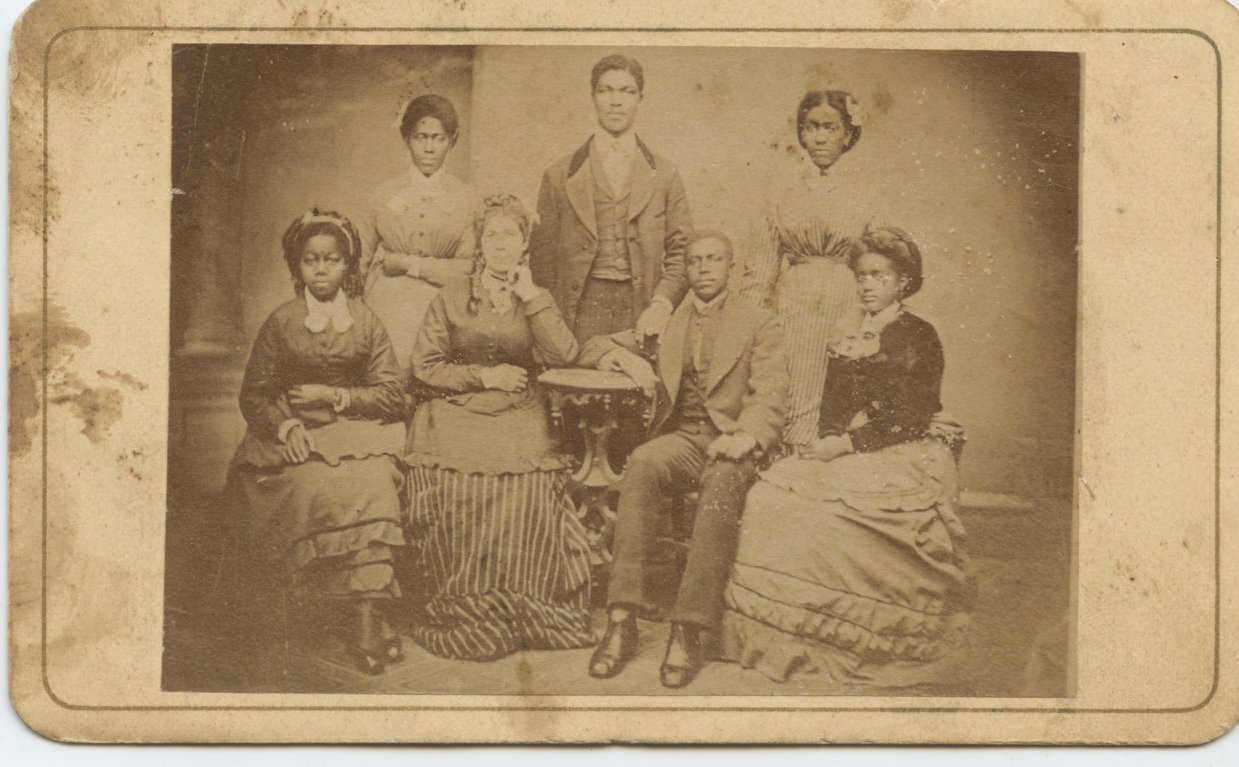

Benjamin Black Elk used the platform of Mount Rushmore to tell a different side of the mountain’s history. Travel Division, South Dakota Department of Highways/South Dakota State Historical Society, used with permission

The story told in this play was, of course, fabrication, a pageant the type of which was common throughout the American West in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Like Los Angeles’s famous La Fiesta play, which told a romanticized version of the city’s Spanish colonial history, the Rushmore pageant was an exercise in mythmaking. Just as La Fiesta sanitized and whitewashed a complex history of religion, imperialism, and Indigenous resistance, the story told at Rushmore in 1939 papered over inconvenient elements such as the thousands of years of Indigenous history prior to the region’s “discovery” by 18th-century French traders, or indeed the violent and bloody seizure of the land by American authorities in the 1870s. In both instances, the performances dramatized history as white settlers preferred to imagine it had transpired, rather than anything close to truth.

Mount Rushmore is a place dense with this type of mythologized storytelling. Danish American sculptor Gutzon Borglum designed the monument, but only after his experience designing and working on the memorial to the Confederacy and the Lost Cause at Stone Mountain in Georgia. While the message of Rushmore was always more nationally minded than the Confederate monument at Stone Mountain, both memorials were more interested in presenting myth than history. Rushmore was self-consciously a monument to American expansion and imperialism, memorializing men Borglum called “a group of empire makers.” While Rushmore today is marketed as a “shrine of democracy,” an American sacred space, it is also a monument to early 20th-century celebrations of American hemispheric hegemony.

Here in the early decades of the 21st century, the stories told at Mount Rushmore are also more varied. A visitor exploring the site today can learn not just about the four presidents on the mountainside, but also the history of its designer, the workers who performed the carving, and the monument’s tourist legacy. Exhibits abound explaining in detail the early 20th-century carving techniques that wrenched faces out of the stone. While the underlying message of American patriotic exceptionalism remains, Rushmore today is also a museum to the histories of 20th-century engineering, art, and tourism.

Rushmore was self-consciously a monument to American expansion and imperialism.

In this way, Rushmore is of a piece with all the sites managed by the National Park Service (NPS). National parks, monuments, historic sites, and other NPS units are rich locations for historical storytelling. As reported in Imperiled Promise, the 2012 landmark study undertaken by the Organization of American Historians and the NPS, the units of the national park system are among the leading institutions for historical education in the United States today. “The NPS,” the authors wrote, has, in the early 21st century, become “the leading curator and interpreter of the nation’s past,” although various factors have made living up to that mantle challenging. While the NPS began as a bureaucratic entity tasked with overseeing spectacular nonhuman environments, expansions in the organization’s mission in the 1930s and the 1970s saw large numbers of human structures and landscapes fall under its purview. Today, the majority of sites managed by the NPS are primarily about human history. Even “traditional” national parks such as Yellowstone and Yosemite maintain waysides and museum space focused on the human story of the park. The NPS stewards not just America’s beautiful places but its bountiful history. They are storytelling places, first and foremost.

At Rushmore, people have recognized the storytelling power of place for a very long time. Despite the story of American exceptionalism blaring from the mountainside, Native people have worked to ensure their stories of the mountain and the surrounding Black Hills were told too. From the late 1940s through the early 1970s, Benjamin Black Elk used the platform of Mount Rushmore—one of the NPS’s, and indeed the nation’s, foremost tourist attractions then and now—to tell a different side of the mountain’s history. Despite not being an NPS employee, Black Elk (the son of Lakota spiritual leader Nicholas Black Elk), appeared at Rushmore regularly during the tourist season, posing for photographs and talking with visitors about Lakota culture and the Native history of the Black Hills. As Native educator and scholar Donovin Sprague (Miniconjou Lakota) said in a 2009 interview, “I think people learned a lot from him, and I know they learned who the Black Hills belonged to.” Black Elk ensured that, amid the stories of American expansion, American art, and American engineering, Indigenous history remained part of the stories told at the mountain.

In January 2024, Mount Rushmore hired me as a postdoctoral fellow in a partnership program between the NPS and the Mellon Foundation. The program’s goal was to “develop new interpretive and educational programming” within the parks through original research conducted via cooperation between scholars, mentors within the park service, and community partners. My specific project was to explore the linkages between Indigenous arts and culture and tourism in the Black Hills, specifically through the lens of the monument at Mount Rushmore. Exploring the history of people like Ben Black Elk and other Native culture bearers who kept Indigenous history alive at this site was to be a major focus of my work.

I use the past tense because the National Park Service determined in March 2025 that it could not maintain its relationship with the Mellon Foundation while also adhering to the Trump administration’s policies. In particular, the program fell afoul of the February 26 executive order creating the so-called Department of Government Efficiency and ordering department heads to “review contracts and grants and . . . terminate or modify such contracts and grants to . . . advance the policies of [Trump’s] administration.” Within one month, the NPS terminated the program, with much work—at Mount Rushmore and at sites across the United States, from Guam to upstate New York—left unfinished.

Native people have worked to ensure their stories of the mountain and the surrounding Black Hills were told too.

This administration does not want alternate stories and broader histories told at places like Mount Rushmore. It is a complicated thing to look at the 60-foot face of Theodore Roosevelt, who asserted that “nine out of ten” Indians were better off dead than alive, and then consider why Black Elk thought this a necessary place to talk about Lakota history and culture. Questions like these do not serve the administration’s mission of, to quote another recent executive order, “remind[ing] Americans of our . . . unmatched record of advancing liberty.” Indeed, histories like Black Elk’s force us to ask, whose liberties have been advanced, and at whose expense?

History is about telling truths, all truths, even truths that complicate the easy narratives embedded in places like Mount Rushmore. For the National Park Service to continue to steward truths about the American past, individual national park sites cannot succumb to myth. Places do not belong to just one person, or to just one story; Rushmore is not, and cannot be, just Rushmore, and it is up to historians to ensure the entire spectrum of history continues to be available to all those millions who visit the national parks.

Stephen R. Hausmann is assistant professor of history at Appalachian State University. In 2024–25, he was an NPS-Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow at Mount Rushmore National Memorial.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.