This post marks the fifth in a series on what we’ve come to call the Career Diversity Five Skills—five things graduate students need to succeed as professors and in careers beyond the academy:

- Communication, in a variety of media and to a variety of audiences

- Collaboration, especially with people who might not share your worldview

- Quantitative literacy, a basic ability to understand and communicate information presented in quantitative form

- Intellectual self-confidence, the ability to work beyond subject matter expertise, to be nimble and imaginative in projects and plans

- Digital literacy, a basic familiarity with digital tools and platforms

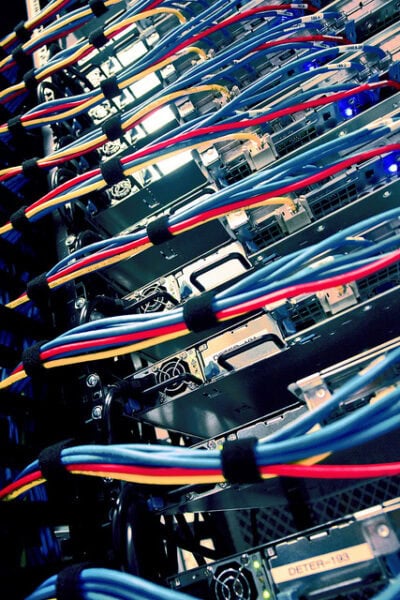

In today’s networked world, historians need to be strategic and organized about developing digital literacy. Image: Andrew Hart, Flikr, CC BY-SA 2.0.

Before the personal computers on our desks were linked to a vast global network, computer literacy meant learning to use programs, such as word processing software, that ran on those machines. In the past two decades, however, these technologies for individual production have been vastly overshadowed by the networking capabilities of the Internet. So digital literacy, as it is now called, is no longer primarily about the standalone things we do on our computers. It is about a familiarity with and facility in navigating and using the network.

At a basic level, historians can expect every aspect of their academic and professional lives to involve using networked digital tools of one kind or another, often in the most quotidian ways—using the university’s digital library catalog, sharing reports with managers and colleagues, working on draft chapters via e-mail with a co-author, or doing keyword searches of the North China Herald online. Forming these connections to colleagues, to knowledge, and to information from across the world requires historians to gain skills and develop competencies that enable the other four Career Diversity skills that have been covered previously.

As many university librarians do, Cornell’s have provided a set of pages on their website on the subject of digital literacy. They define digital literacy as “the ability to find, evaluate, utilize, share, and create content using information technologies and the Internet.” While this particular definition is aimed at undergraduates, it’s also a valuable starting place for many graduate students.

Developing digital literacy often requires strategic thinking. Just as the research and writing process for a dissertation or book requires planning, so does acquiring digital literacy. Many graduate students assume that everyday use of Facebook, Snapchat, or Instagram makes one automatically digitally literate. The concept of the digital native, however, is largely a myth built upon generational thinking, and growing up in a media-saturated, connected world does not in and of itself make one digitally literate or media savvy—there is a basic fallacy in assuming that that we are more likely to have critical faculties about the things we do reflexively and daily. On the other hand, the digital literacy needs of a graduate student looking for a job require intentionality and reflection, not to mention a willingness to take risks and chances. You would be well served to figure out what sorts of digital skills you need and then pursue them deliberately.

A disciplinary and professional digital literacy also means having a basic knowledge of the impact of using digital technologies in all aspects of your working life. As teachers, digital literacy enables you to make better use of tools such as PowerPoint and learning management systems to improve the quality of your students’ education. Adopting innovative assignments, such as challenging students to critically evaluate (and even edit) Wikipedia, rather than banning its use, for example, can help students become more digitally savvy and prepared for success in the world. As researchers, digital literacy can lend a more critical understanding of how keyword search might provide a different window to the past than more traditional means of primary source discovery. It might also give insights into the conditions that affected the creation and archiving of born digital sources. Digital literacy also means knowing the value of social media and other online platforms for exchanging ideas with others in our field (and knowing when this is a waste of time), and (dare I say it) self-promotion. It’s also about not assuming that blogging is a distraction from, rather than a potential contribution to, more traditional scholarly outputs. It’s also about knowing when you don’t know something and where to find help.

How does one obtain this elusive digital literacy? The first step for graduate students is to seek out resources at your institution. Your university’s website, the library, the campus center for teaching and learning, and IT services will all provide resources for helping you get started or build your knowledge in many of the key areas of digital literacy. Some institutions run workshops, seminars, and even entire programs on these skills.

As you develop expertise, four fundamental areas should be your focus: First, learn to manage your online identity because “If you don’t, someone else will.” (Many academic and nonacademic employers google applicants they are considering interviewing.) Second, be familiar with digital tools for research, teaching, and scholarly communication. Even a basic knowledge of tools that can help organize your work, such as citation management software, will be a step toward greater fluency. Third, once you have that basic knowledge, use these tools with a critical eye. Build up an understanding of how digital tools such as learning management systems, keyword searchable full text databases, and web-based publication software are changing intellectual production. And finally, be prepared to explain how these skills and knowledge make you a better candidate on both the academic and nonacademic job market.

This may seem like a lot, but it’s probable that you are already doing many of these things. Keep in mind that you don’t need to become an expert in everything. Building up a strategic and intentional digital literacy means learning and using the tools that help you become a better historian. Language learning provides a helpful metaphor here. Gaining fluency in a language is a difficult undertaking that requires many years. Between that level of skill and complete ignorance there are many stages, and even just knowing a few words of the local language can make a vacation more interesting and enjoyable. Digital literacy is the same. Seek out training about the tools that are most relevant, and develop your skills to the level you require.

Digital literacy is invaluable no matter where your career takes you. Recognize the skills you already have, cultivate those you need, and remember that all of this work will open doors and bring opportunities.

For more information on quantitative literacy and the rest of the “five skills,” check out our new page www.historians.org/fiveskills and the rest of the contributions to this series.

*I want to thank everyone who responded to my cry for help on Twitter. The brief but thoughtful exchange there helped me to solidify some of these ideas. In particular Trip Kirkpatrick gave me the metaphor of language learning, and Alan Pike provided the link to the wonderful syllabusthat he and his colleagues at the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship have developed.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.