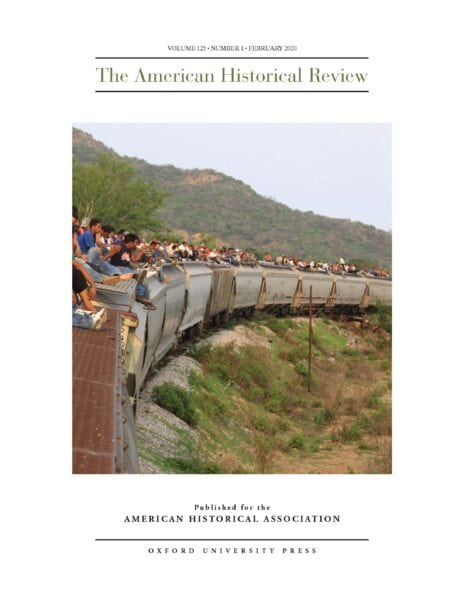

Catching a ride atop a freight train has become a common, albeit extremely dangerous, way for Central American migrants and refugees to cross Mexico in their desperate attempts to reach the United States. Countless migrants have lost limbs and even their lives to “La Bestia” (The Beast). In “Offshoring Migration Control: Guatemalan Transmigrants and the Construction of Mexico as a Buffer Zone,” Ana Raquel Minian details efforts by US officials in the 1980s to pressure Mexican policy makers into obstructing the movement of Central Americans heading for the US through Mexico. In return, Mexican workers would be allowed to continue crossing the border with impunity. By agreeing to enforce US immigration interests, Minian argues, Mexico’s leaders effectively surrendered their country’s sovereign right to determine who should be allowed to immigrate. Moreover, Minian asserts, shifting the responsibility for border control to the Mexican government, which has made little progress toward eliminating the human-smuggling business, led to greater violence against the migrants and opened the door to widespread human rights abuses. Image courtesy of Albergue de Migrantes “Hermanos en el Camino.”

As a wise man once said, “Everything has a history.” Although many of the human-rights abuses embedded in current immigration and refugee policies at the US–Mexico border appear to spring from the white nationalism of President Donald Trump and Stephen Miller, in fact the construction of Mexico as an immigration “buffer zone” draws on a deep well of prior practice. As Ana Raquel Minian (Stanford Univ.) shows in her article in the February issue, “Offshoring Migration Control: Guatemalan Transmigrants and the Construction of Mexico as a Buffer Zone,” during the 1980s US officials pressured Mexican authorities to limit that nation’s sovereign determination of immigration enforcement. In exchange for Mexican suppression of Central American migration at its southern border, US policy makers turned a blind eye to Mexican migration northward. The universalist idea that human rights fell under a transnational mandate, Minian shows, extended migratory controls beyond individual nation-states. Ironically, in Mexico and Central America, such erosion of sovereignty opened the door to increased human rights violations against those fleeing persecution. Today, a new generation escaping violence and poverty in Central America faces a similar situation as they travel through Mexico on their perilous journey to the US.

The February issue contains a second article on recent Latin American history, this one on the complex environmental history of an endangered Peruvian quadruped, the vicuña. By midcentury, this small Andean llama-like species faced extinction due to the value of its wool. As Emily Wakild (Boise State Univ.) explains in “Saving the Vicuña: The Political, Biophysical, and Cultural History of Wild Animal Conservation in Peru, 1964–2000,” the Peruvian government—despite significant regime shifts—initiated a series of conservation measures, including trade restrictions and a territorial reserve, that allowed the vicuña population to rebound. Wakild’s article argues that conservation reoriented cultural, biological, and economic relationships among people and wild animals. Affinities between Andean peoples and local fauna led to ethical claims of the animal’s value as well as utilitarian arguments for its potential economic contribution to community development. Moreover, Wakild maintains, the vicuña themselves shaped the conservation programs with their biological habits. Attention to the measures to save the vicuña, she concludes, illuminates past environmental actions of politically volatile, economically marginalized, and socially divided nations.

Attention to the measures to save the vicuña illuminates past environmental actions of politically volatile, economically marginalized, and socially divided nations.

The potential historiographical gains made by increased attention to the natural world is, in fact, the subject of John R. McNeill’s (Georgetown Univ.) AHA Presidential Address from the 2020 annual meeting. In “Peak Document and the Future of History,” McNeill contemplates the flood of new information about the past disclosed by the natural sciences and archaeology rather than written documents. Appropriately enough for this address, McNeill’s contribution looks not only to the past but to the potential future of historical practice. He warns that, with each passing year, the proportion of our knowledge of the past that derives from the kinds of documents we have learned to read and interpret will shrink, and the proportion dependent on scientific evidence will mount. McNeill presents a series of pressing questions about how such evidence might reorient our interpretive paradigms and reconfigure graduate training. Intellectual excitement, he suggests, may tip toward the study of earlier centuries, where there is a cluster of information in nonwritten formats. Moreover, graduate training may need to accommodate techniques to understand this new evidence. McNeill finds a partial guide to our future as historians in the experience of precolonial Africanists, who are accustomed to research without written documents.

Another article, Sebastian Conrad’s (Free Univ. of Berlin) “Greek in Their Own Way: Writing India and Japan into the World History of Architecture at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,” considers the transnational history of architecture and aesthetics. Conrad compares the careers of two architectural scholars—Itō Chūta in Japan and Rajendralal Mitra in Bengal—who challenged Eurocentric accounts of aesthetic modernity by insisting on the inclusion of Japanese and Indian building traditions in the world history of architecture. In distinctive fashion, they each mobilized the idea of classical Greece to create protonational architectural traditions. Itō saw ancient Japanese buildings as directly influenced by Greek models, while Mitra posited Indian originality by rejecting any such connections. Yet both men deployed aesthetic references to “Greece” in order to place their native architecture on a world stage. While invoking a Eurocentric standard to battle Eurocentrism may sound paradoxical, Conrad demonstrates that a confluence of global forces went into the making of this late-Victorian moment of imperial global idealism. The proclaimed universalism of the aesthetic standards appealed to by Itō and Mitra do not represent a gradual spread and diffusion from a European center, Conrad insists. Rather, local intellectual elites constantly invented and co-produced such standards as they resonated both with global integration and the social dynamics of emergent national identity at the more local level.

Readers will also find a pair of contributions to our ongoing “History Unclassified” series; both essays urge us to “read between the lines.”

In addition to these four article-length features, the February AHR offers the usual eclectic mix of shorter pieces. Brett Edward Whalen (Univ. of North Carolina) offers a timely reappraisal of Ernst H. Kantorowicz’s 1957 study The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology. As Whalen relates, a growing awareness of where this important book fits into the trajectory of Kantorowicz’s life and early career in 1920s and 1930s Germany has reshaped scholarly analyses of his famous work over the past several decades. Kantorowicz’s study of medieval political theology, Whalen observes, can be read as an oblique challenge to 20th-century theories about the theological origins of modern sovereignty.

Readers will also find a pair of contributions to our ongoing “History Unclassified” series, Argyro Nicolaou’s “Archive Fever: Literature, Illegibility, and Historical Method” and Emily Callaci’s “On Acknowledgments.” Both essays urge us to “read between the lines.” Nicolaou (Princeton Univ.), a filmmaker and scholar of modern Greek literary culture, uses a found fragment from the papers of the Greek Egyptian novelist Stratis Tsirkas (1911–1980) to explore the allure of illegibility in the archive. Adapting methods from literary analysis and visual art, Nicolaou attempts to decipher a hastily scribbled note on a 1929 film flyer advertising the screening of two Hollywood movies in Cairo. In her attempt to render this inscrutable text legible, she reconstructs the moment of the archival fragment’s production by imagining a technique called “reverse calligraphy.” Her sensory engagement with the archive’s materiality illuminates both Tsirkas’s complex political biography as an interwar Greco-Egyptian communist and the role of creative interpretation in historical inquiry. Callaci (Univ. of Wisconsin), whose essay the AHR has already made open online over the past few months, considers what readers might decode from a close scrutiny of the acknowledgments in academic books. She maintains that these intended expressions of gratitude help us map intellectual communities, yet they inadvertently reveal some of the processes of exclusion that shape academia.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.