For the past 18 months, I have been supporting the ground-level research for Where Historians Work, AHA’s interactive database of cross-institutional data on history PhD job outcomes. After many long hours of finding, categorizing, and updating current employment information for thousands of historians, I can say with confidence that I am no longer surprised by any of their career choices. I’ve found sports coaches, movie producers, farmworkers, mechanical engineers, software developers, and many others working in fields where a history PhD is definitely not the prerequisite.

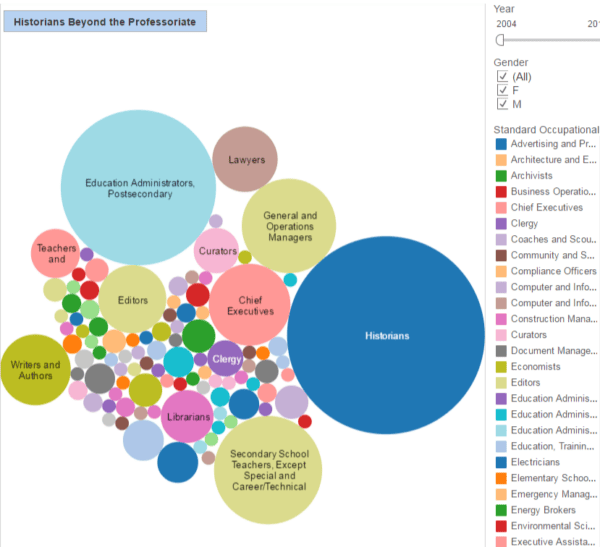

The third slide of the Where Historians Work storyboard shows a chart capturing data on “Historians Beyond the Professoriate.”

While Where Historians Work exposes a rich variety of nontraditional jobs, it tells us little about the processes that led graduates into these fields. So we reached out to a few of the faces behind the data, mainly to get a sense of whether they still feel like they “belong” to the history world in the same way that teachers and researchers do, and to find out how their training as historians shapes their careers.

It’s easy to find these individuals in the visualizations. We have integrated the US Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) detailed occupational code system into Where Historians Work to better link the records to outside data. Out of 840 possible codes, we’ve found PhDs whose jobs match the description of nearly 150. That includes everything from the average history professor (code title “History Teachers, Postsecondary”) to “Pest Control Workers.” There’s no doubt we will add more codes to the total as we finish collecting and refining data from the 130 US PhD programs not yet included in the current display.

The third slide of the storyboard, “Historians beyond the Professoriate,” is a chart of all the BLS codes we have found, excluding tenure-track and non-tenure-track faculty. While you’ll notice that the large bubbles represent common occupations that many would assume attract a lot of historians (“writers and authors,” “education administrators”), the smaller bubbles denote rarer careers that might seem unusual or unexpected.

Dianne Cappiello is one of slide 3’s two “Human Resources Specialists.” She graduated with a PhD in American history from Cornell University in 2011, and currently serves as human resources manager at a nonprofit organization in Binghamton, New York. Like others before her, she became disillusioned with the academic job search process and decided to revisit an undergraduate interest in human resources. She even went back to school to complete a graduate certificate in human resources management.

While applying for HR positions, Cappiello almost did something unthinkable: leave her PhD off her resume. But she soon resolved to embrace her background with the mantra, “I am who I am.” Cappiello has since found that her academic training allows her to excel at the analytical components of job duties like payroll, benefits administration, and federal compliance. “People sometimes comment to me how awful it is to waste my education,” she says. Unfazed, she continues, “I love my job and am performing meaningful work in a mission-oriented company.”

The AHA knows that the skills historians have are transferable to many careers. But it is also clear that their mastery of content knowledge is valuable outside of the academy. This is the case for Lisi Martinez Lotz, who as member services coordinator at the North Carolina Coalition Against Domestic Violence, coordinates efforts to prevent domestic violence in local communities. As a graduate student at UNC Chapel Hill, Lotz studied Latin American history with a specialization in gender issues. Informed by her expertise, Lotz was ideally situated to develop a Latinx services program in her organization.

“The classes that allowed me to question patriarchy, colonialism, oppression, and racism particularly resonate with what I do now,” Lotz comments. And while the job focuses much more on the present and future, the study of the past continues to shape how Lotz approaches the mission of her organization: “Movements in and of themselves look for ways in which present actions can influence the future. That being said, my experiences as a student, teaching assistant, lecturer, and historian shaped how I understand the world. It also provided me with the analytical skills to examine current realities and impart that information through trainings to people who work with survivors.”

Todd Leahy, deputy director of the New Mexico Wildlife Federation, also connects his research interests to his work. Leahy received his PhD from Oklahoma State with a dissertation titled, “The Canton Asylum: Indians, Psychiatrists, and Government Policy, 1899–1934.” “Much of my work at the New Mexico Wildlife Federation has centered on working with tribal communities on environmental and legal issues,” he writes. “To understand that relationship, one must have a firm grasp on the history of the relationship between the federal government, tribal people, and environmental groups. So much of my work involves taking large amounts of information from diverse sources and synthesizing that into intelligible content—the training I had as an historian has made that possible.”

If all of the interviewees have a narrative in common, it’s that each of them entered graduate school with the expectation that they would end up in the academy. As Lotz puts it succinctly, “I had always planned on being a professor.” But at different times and through different circumstances, they reached the conclusion that the professoriate was not the best fit for them. While these are only three stories out of literally hundreds to pick out from the data, it’s worth emphasizing that these “outliers” feel extremely rewarded in their work and continue to identify themselves as historians. “There is life outside the academy,” Cappiello emphasizes. “Embrace it!”

Check out these previous AHA Today posts for tips on how to “find yourself” in the Where Historians Work data, and advice on how graduate students can utilize the tool.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.