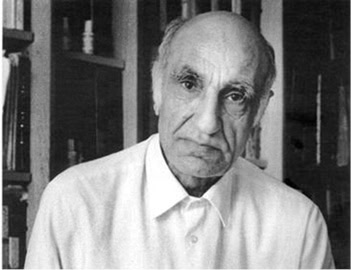

Mohammad Ebrahim Bastani-Parizi. Credit: Bokhara magazine. Photo by Maryam Zandi

Mohammad Ebrahim Bastani-Parizi was born on December 24, 1925, in Pariz, a small village located at an elevation of 7,500 feet in Kerman Province, in remote southeastern Iran. It was not until he had reached the age of 11, in 1937, that he set foot outside of Pariz for the first time. He attended high school in Sirjan, the nearest (small) town, until ninth grade, and finished his secondary education in Kerman, the capital and main urban center of the province. The Persian translation of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, a book that has remained very popular in Iran to this day, was one of his few windows on the world at that time. In 1946, he went on to pursue higher education at the Daneshsara-ye Ali in Tehran. Having obtained a degree from that institute of higher learning in 1951, he initially returned to Kerman to serve as headmaster of the local secondary school. In 1958, he went back to the capital to enroll in the newly established PhD in History program at the University of Tehran. He received his doctoral degree in 1963, and subsequently took up a teaching position at his alma mater. In 1970, he spent a sabbatical year in Paris, memorably recounted in his autobiography, Az Pariz ta Paris (From Pariz to Paris). He was to remain at the University of Tehran, serving as the chairman of the history department for a number of years, until his retirement in the summer of 2008. He passed away on March 25, 2014, leaving behind a son in Tehran and a daughter in Toronto, Canada.

Bastani-Parizi, who wrote his first newspaper article in 1942, was a prolific writer, the author of over 60 books and hundreds of articles on many aspects of Iranian history and especially on the local history and geography of Kerman. Many of his monographs went through numerous editions, and several have never gone out of print. He was a published poet as well, and over the years he translated a number of works from the Arabic and the French.

Above all, Bastani-Parizi was a naqqal, a storyteller in the traditional mode of Iran, rooted in the soil, attuned to local traditions, ancient tales, and legends. Having grown up in a country as yet relatively untouched by modern development, he had an intimate knowledge of and a deep affinity with the land, village life, peasants, and their beliefs and superstitions. His writing was a blend of historical observations, anecdotal asides, and personal experience. His way of writing history was a matter of digging into the soil of Iran to unearth the deep vein of popular legend and lore, all of which he presented in books and articles written in a conversational style mixing erudition and humor.

For Bastani-Parizi, regional history was an essential part of the historian’s craft, allowing for the kind of detail and texture and attention to human action that national history cannot achieve to the same degree. Kerman, the city and the eponymous province, was and remained the center of his world, the region from which he hailed and which he loved. Its architecture, its material history, its mythology, and its magic were to him the repository of ancient wisdom, the epitome of Iranian history, and the fountainhead of his imagination. In a style that was simple yet rich and evocative, he brought out the accumulated wisdom from his ancestral region in a series of studies about Kerman and its important role in Iranian history, especially in the Safavid period, from the 16th to the early 18th century. In addition, he edited and annotated a number of regional chronicles describing life and politics in Kerman in the early modern period, rare and even unique sources such as the Tarikh-e Safaviya-ye Kerman, the Sahifat al-Ershad, and the Tarikh-e Vaziri.

On a wider, national Iranian canvas, Bastani-Parizi wrote a number of notable works. Some of these address various Islamic dynasties and prominent rulers. Others deal with aspects of geography, economics, and material history. Especially noteworthy is his research on the transmission of sites, concepts, and names between pre-Islamic, Zoroastrian times and the Islamic period. In one of his most well-known books, Khatun-e haft qal`eh (The Lady of the Seven Castles), he argues that many names in early Islamic history in reality refer to the locations of temples or the ancient Iranian cult of Anahita or Nahid, and thus have feminine roots associated with fertility, healing, and purity. He also contributed to the six-volume UNESCO History of Civilizations of Central Asia.

Bastani-Parizi’s history writing might seem unencumbered by theory. Yet it was suffused with a philosophy of history. He saw the specificity of place, the singularity of time, and the primacy of human action as the three animating forces of history that, if properly applied, might overcome the dichotomy between materialist and idealist historiography. Unlike many of his Iranian contemporaries, he was not ideologically committed, not because he thought politics was unimportant but because he fully realized that today’s fashion and unassailable truth might be tomorrow’s abomination. Hence the ironic tone, the humility, the evenhandedness, and the humanism of his historical approach. History to him was a society’s necessary conscience and consciousness, and the historian a doctor in search of the ills of a community of humans, in the full awareness that his remedies may not be free of error.

In 2011, an 800-page volume Hezaran sal-e ensan (Thousands of Years of being Human) was published with an extended interview with Bastani-Parizi about his life and work, as well as reminiscences about his teachers and colleagues. His latest work, Kuh-ha ba hamand (Mountains Stay Together), is to be published posthumously.

Bastani-Parizi was famous for his unadorned, down-to-earth ways, symbolized by his refusal to wear a tie—long before the Islamic Republic disapproved of such attire for different reasons, and beloved for his gentle nature and demeanor. By his own admission, he found it impossible to dislike anyone. There is no question that everyone who knew him loved Bastani-Parizi, his kindness, his gregariousness, and his inexhaustible stories. Iran has lost one of its great historians. He will be dearly missed.

Rudi Matthee

University of Delaware

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.