One hundred and forty characters doesn’t sound substantial, but as Twitter has proven in the last eight years, it’s enough to establish (or ruin) a reputation, crowd-source a revolution, and even assemble a community. The latter is exactly what historian and blogger Katrina Gulliver (@katrinagulliver) did in September 2007. Just one year after Twitter launched, Gulliver posted a tweet looking for other historians to connect with on Twitter and eventually created #Twitterstorians, a comprehensive conversation channel for history professionals. This month we commemorate the five-year anniversary of Gulliver’s proverbial smoke signal, a significant step in organizing and centering historians’ interactions with one another in social media.

To mark the occasion, I took a step back and considered the virtues and vices of the Twittersphere. Twitter is much hyped, but is it worth anything? Are we actually connecting with one another and exchanging ideas, or are we merely tweeting in a shared space without any meaningful discourse?

In an attempt to answer these questions, I experimented with network data from Twitter using NodeXL, a social media network analysis tool that extracts data from networks like Twitter and presents it visually, enabling users to explore the structure, size, and key relationships of Twitter communities. Lines between users represent the connections they form when they follow, reply to, or mention each other. After I pulled data from roughly 1,117 users of the Twitterstorians hashtag, Marc Smith, a developer of the software, generously produced the three visualizations that appear in this piece.

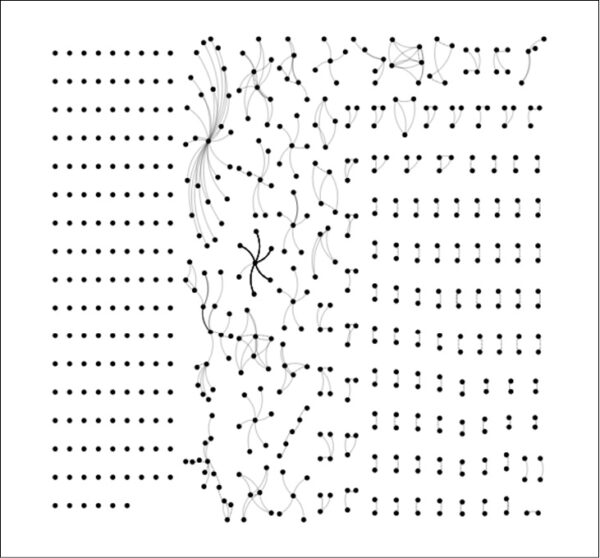

Smith and the Pew Research Center used NodeXL to help classify different types of crowds on Twitter. The Twitterstorians channel (fig. 1) matches their description of a “tight crowd network.”1 Such a network is characterized by a dense web of users who follow each other, share, and engage with tweets; that web—the thick groupings of lines that connect users and reach their highest concentration in obvious nodes—indicates a high volume of information sharing or conversation within the channel.

Figure 1. A map of networks using the #Twitterstorians hashtag.

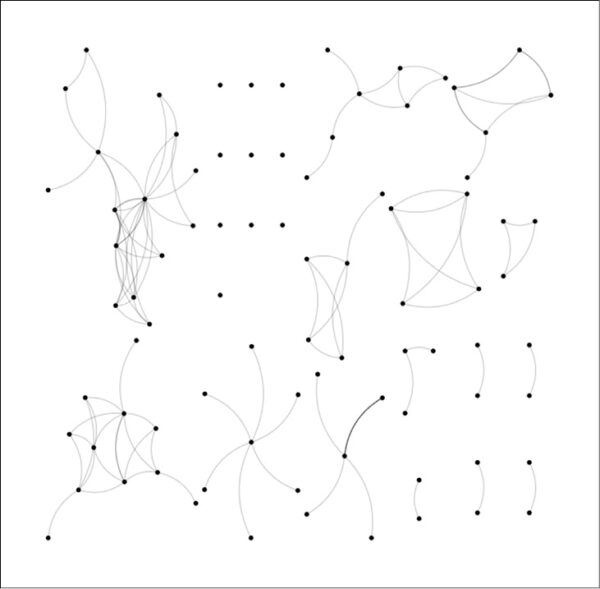

This is even more apparent when one compares the Twitterstorians map to the one that plots #History tweets (fig. 2). The “history” hashtag is more broadly used on Twitter, but there is little meaningful dialogue, and participants have little to no interaction or connection with one another. This is evident in the large numbers of isolated users (“isolates”) who appear on the map.

Figure 2. A map of the #History hashtag shows little conversation taking place.

The maps tell only part of the story. The types of conversations happening within these communities are far more significant in telling us why these communities take the shapes they do. With #Twitterstorians, conversation often begins when users solicit professional advice or ask for research suggestions; popular word pairs include looking/someone, suggestions/twitterstorians, and interview/help. The top word pairs in #History, on the other hand, are free/ebook, standing/Israel, and history/history. Most of the #History tweets are undirected and not intended to spark conversation, while tweets using #Twitterstorians are often overtures for help and suggestions.

Information seeking and networking, whether motivated by a desire for discussion or the simple wish to follow another tweeter, are key to creating a supportive, collaborative group. #PublicHistory is a smaller community than #Twitterstorians, but it exhibits similar conversational behavior (fig. 3).

Figure 3. A map of the #Publichistory hashtag bears similarities to the #Twitterstorians map.

Most of the users of #PublicHistory fall into cluster groupings, particularly in the upper and lower left-hand side of figure 3. Users in this channel frequently share conference information or crowd-source questions. Top word pairs include questions/history, big/congrats, and big/questions.

Overall, the maps suggest that historians on Twitter have built personalized communities of responsive and engaged professionals who solicit feedback and are willing to discuss research and professional matters. What the maps do not show, however, is how the social and professional connections forged on Twitter impact the profession as a whole. How are historians capitalizing on the #Twitterstorians community outside of Twitter? We already know that Twitter is playing a much larger role in how www.historians.organize and promote conferences, but are they actually using the platform as a tool for collaboration, as the tweets suggest? Lastly, it would be worth investigating the demographic information about the users in the #Twitterstorians channel. Is the map in figure 1 a microcosm of the discipline or a very narrow grouping?

Why are these maps useful? Social media networks come in many different sizes and structures, and they behave in radically different ways depending on the people in them. Maps such as these help us understand the behavior of users in a given topic community and allow us to track the community’s impact on social media. Many historians are using Twitter as a networking and mentoring tool for the discipline. For those of us who use it, Twitter is a space in which to connect, engage in public discussions and debate, share research, and even form friendships that extend beyond our professional lives. For those who have not yet joined the Twitter community, consider this the perfect time to shed preconceived notions of what Twitter may be and consider what historians have already made of it.

Vanessa Varin served as the AHA’s associate editor, web content and social media.

Special thanks to Marc Smith, director of the Social Media Research Foundation (smrfoundation.org), for generating the NodeXL maps in this piece. See more at nodexl.codeplex.com.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.