In his essay “Many Thousands Gone,” the 20th-century novelist and social critic James Baldwin observed, “The story of the Negro in America is the story of America—or, more precisely, it is the story of Americans. It is not a very pretty story[.]” In the passage and the essay, Baldwin pointedly condemns how popular culture reinforces stereotypes of African Americans. But had he written the essay today, more than 60 years later, he could have just as easily been describing what is going on in introductory US history courses.

Because, in 2017, the story of African Americans enrolled in introductory US history courses is the story of the course itself. More precisely, it is the story of all students, particularly those from historically underrepresented backgrounds, who enroll in the course. And it, too, is not a pretty story. This may seem hyperbolic, but it is supported by evidence.

Over the past three years, 32 colleges and universities have worked with the nonprofit organization I serve—the John N. Gardner Institute for Excellence in Undergraduate Education—to produce a study of introductory US history courses. This analysis was conducted with the help of my colleague, Brent M. Drake, the chief data officer at Purdue University and a research fellow at the Gardner Institute, who also helped with the data analysis in this article. The Gardner Institute’s mission is to work with postsecondary educators to increase institutional responsibility for and outcomes associated with teaching, learning, retention, and completion. Through these efforts, the institute strives to advance higher education’s larger goal of achieving equity and social justice. I had the privilege of presenting the findings as part of a preconference workshop at the 2017 AHA annual meeting.

Our data set includes outcomes for nearly 28,000 students enrolled in an introductory US history course at one of the 32 institutions during the academic years 2012–13, 2013–14, and 2014–15. These institutions included 7 independent four-year institutions, 6 community colleges, 2 proprietary institutions, 5 public research universities, and 12 regional comprehensive public institutions, and all agreed to have their data included in the study. From the data, we sought aggregate and disaggregated rates of D, F, W (any form of withdrawal), and I (incomplete) grades in introductory US history courses. While not perfectly representative, the data allow for meaningful scrutiny of who succeeds and who fails in introductory US history courses.

The range of DFWI grades in these courses across the 32 institutions was 5.66 percent to 48.89 percent, and the average DFWI rate was 25.50 percent. This means that nearly three quarters of all students enrolled earned a C or better. One could argue that this DFWI rate results simply from upholding standards and rigor. But troubling trends emerge upon disaggregating the same data by demographic variables—trends that may very well reveal that the term “rigor” enables institutionalized inequity to persist.

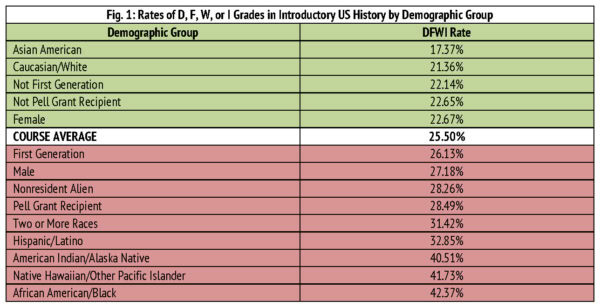

Figure 1: Rates of D, F, W, or I Grades in Introductory US History by Demographic Group

Race, family income levels (based on whether a student receives a Pell Grant), gender, and status as a first-generation college student are the best predictors of who will or will not succeed in introductory US history courses. As fig. 1 shows, the likelihood of earning a D, F, W, or I grade is lower for Asian American, white, and female students who are not first generation and do not receive a Pell Grant. It is higher, sometimes significantly higher, for every other demographic group.

Some see failing a course as beneficial: it can be a reality check that helps students learn what is necessary to succeed in college and may even help point toward programs for which they are “better suited.” The problem with that consoling argument is the fact that for some students, failure in even one course such as introductory US history predicts ultimate dropout from college altogether.

Institutional dropout rates show that the students who took introductory US history, were otherwise in overall good academic standing, and opted not to return to the institution the following year were over twice as likely to have earned a D, F, W, or I in the course (42.87 percent) than retained students in good academic standing (19.27 percent). Failure in the course, therefore, was not necessarily an indicator of being a bad student—because these students were otherwise in good academic standing—but was directly correlated with students’ departure decisions. Adding to these disturbing data are two national studies that show that college students who do not succeed in even one of their foundational-level courses are the least likely to complete a degree at any institution over the 11-year period covered by the studies.1

When one considers the characteristics of students who are more likely to earn a D, F, W, or I in an introductory history course alongside the retention and completion implications, it is clear that there is a problem. And this problem is that many well-established approaches to teaching introductory history and other foundational college courses may be subtly but effectively promoting inequity.

This ugly picture can only get worse if teachers and professionals charged with supporting enrolled students continue with a business-as-usual approach. According to the Western Interstate Commission of Higher Education’s report, Knocking at the College Door, high school graduating class sizes are shrinking. At the same time, the very same populations that are least likely to enroll and succeed in college—underrepresented minority, first-generation, and low-income students—will constitute larger percentages of high school graduates and beginning college students.2 While they might not lack the cognitive wherewithal to learn and succeed, they often lack the cultural capital and sense of social belonging their more advantaged counterparts possess. A single failure can confirm preexisting attitudes that “I’m just not college material” or that “I don’t belong here.”

But there is hope: methods and means that can help counter these trends. Such methods include increasing expectations for our students, engaging with them, and directing them to available academic support.

Our knowledge about what works in postsecondary teaching and learning has advanced significantly since the end of the 20th century. New approaches include the use of evidence-based, active-learning strategies in college courses of various sizes. These strategies improve outcomes for all students, especially those from the least advantaged backgrounds.3 Also showing great promise is the use of embedded (therefore required) support for all students—since, as the higher education researcher Kay McClenny notes, “at-risk students don’t do optional.”4 And providing early and frequent feedback in courses—increasingly by using predictive analytics and intervention mechanisms—also has benefits.5

So now that you know this, what will you do? Will you examine data from your institution to see if comparable trends exist in the courses you teach? If you find them, will you explore the resources available to you and use them to redesign your courses—both their structure and the way you teach them? Will you reach out to students? Will you explore professional development activities provided through your institution’s center for teaching excellence or through entities like the American Historical Association’s Teaching Division or the International Society for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in History?

In an era of “alternative facts” and “extreme vetting,” it is easy to feel powerless. But the issues in introductory history courses—a form of vetting, too—existed long before the atmosphere following the 2016 election. That is not an alternative fact. If inequity in the United States concerns you, and inequitable outcomes exist in the courses you and your colleagues teach, then it is important to remember that you have agency to address this.

As historians, we know that we are agents of history acting in history to shape it. Therefore, I encourage you to shape history by reshaping the history courses you teach. In the process, you may very well be creating a much more hopeful and “prettier” story.

This article is a companion piece to David Pace’s article, “The History Classroom in an Era of Crisis: A Change of Course is Needed.”

Notes

- Clifford Adelman, “Answers in the Toolbox: Academic Intensity, Attendance Patterns, and Bachelor’s Degree Attainment,” Office of Educational Research and Improvement, US Department of Education (1999), https://www2.ed.gov/pubs/Toolbox/toolbox.html and “The Toolbox Revisited: Paths to Degree Completion from High School through College,” Office of Educational Research and Improvement, US Department of Education (2006), https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/research/pubs/toolboxrevisit/. [↩]

- Brian T. Prescott and Peace Bransberger, “Knocking at the College Door: Projections of High School Graduates,” Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (2012), https://knocking.wiche.edu/. [↩]

- Scott Freeman, Sarah L. Eddy, Miles McDonough, Michelle K. Smith, Nnadozie Okoroafor, Hannah Jordt, and Mary Pat Wenderoth, “Active Learning Increases Student Performance in Science, Engineering, and Mathematics,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, no. 23 (2014): 8410–15. J. Patrick McCarthy and Liam Anderson, “Active Learning Techniques versus Traditional Teaching Styles: Two Experiments from History and Political Science,” Innovative Higher Education 24, no. 4 (2000): 279–94. [↩]

- Jim Henry, Holly Bruland, and Jennifer Sano-Franchini, “Course-Embedded Mentoring for First-Year Students: Melding Academic Subject Support with Role Modeling, Psycho-Social Support, and Goal Setting-TA,” International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 5, no. 2 (2011): 16. [↩]

- Kimberly E. Arnold and Matthew D. Pistilli, “Course Signals at Purdue: Using Learning Analytics to Increase Student Success,” in Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Learning Analytics and Knowledge, ACM (2012), 267–70. [↩]

Andrew K. Koch, PhD, is chief operating officer of the John N. Gardner Institute for Excellence in Undergraduate Education. The data informing this analysis will be the subject of a further Gardner Institute report, by Koch and Brent Drake, on introductory courses in multiple subjects and student outcomes.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.