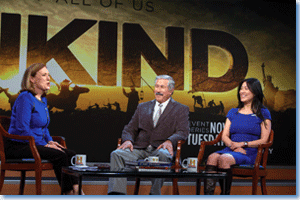

Albert Camarillo and Hzin-Mei Hsu join host Libby O’Connell to discuss UNESCO world heritage sites as part of the History Channel’s Mankind: A Global Teach-In event. Photo courtesy of the History Channel.

The History Channel recently sponsored a global teach-in to address the tendency of textbooks to avoid a global approach to American history—a perspective that often leads students to conclude that America’s story is largely separate from the broader history of humanity. The teach-in brought together historians Albert Camarillo and Hsin-Mei Agnes Hsu with students from across the globe to discuss key events in world history that link nation-states in a shared history.

The panel focused on UNESCO heritage sites because, as Hsu points out: “World heritage sites are not just beautiful things, beautiful places, they tell very powerful stories.” From the slave trading forts in Ghana to the Great Wall of China to the remnants of Auschwitz, UNESCO sites draw millions of people each year, and serve as the primary source for national histories for many of these visitors. There are 962 world heritage sites, including 745 cultural, 188 natural, and 29 mixed.

The participants offered some valuable teaching tips, including how teachers can integrate world heritage sites into their curricula, and how these sites demonstrate to students how national histories often interconnect.

Integrating UNESCO Heritage Sites into Curricula

Like a historical event, highlighting a physical landmark in class discussions offers several useful dimensions for analysis for students. Eric Langhorse, a history teacher in Missouri, described how he brought UNESCO sites—including Monticello and Independence Hall—to the forefront of his teaching curriculum. Likening a UNESCO site to a microhistory, this strategy allows teachers like Langhorse to discuss a wide variety of themes central to American history within a narrow field in which students can focus.

Furthermore, integrating UNESCO sites into curricula is a gateway to approaching issues of preservation with students, and the ways in which younger generations can help preserve world heritage sites. According to Camarillo, preservation and activism is closely tied to an understanding of history. “First they have to do a little history. An appreciation of the history tied to the site … that’s when things begin to change, and you get the attention of others.”

A Global Approach to National Histories

Finally, looking at heritage sites helps students recognize the many ways in which history is a series of exchanges between disparate groups and cultures. As Camarillo noted, “Whether it is the Valparaíso of Chile, whether the slave ports in Ghana, or the Sahr-i-Bahlol parks in Pakistan, the students as they learn this realize it’s not just people from localities, these are the intersecting points where people, cultures from all over the world come together.”

What Camarillo suggests, then, is a much more significant shift in the way history professionals approach the education of landmarks and heritage sites. The Statue of Liberty, one of the most popular heritage sites in the United States, is a quintessential vista in American textbooks and yet its story is a global one—mingling with the stories of millions of immigrants greeted by the statue as they entered New York harbor. Links like these demonstrate that American history does not begin or end in the United States, and approaching these global strands through heritage sites is one way to broach comparative history with K–12 students.