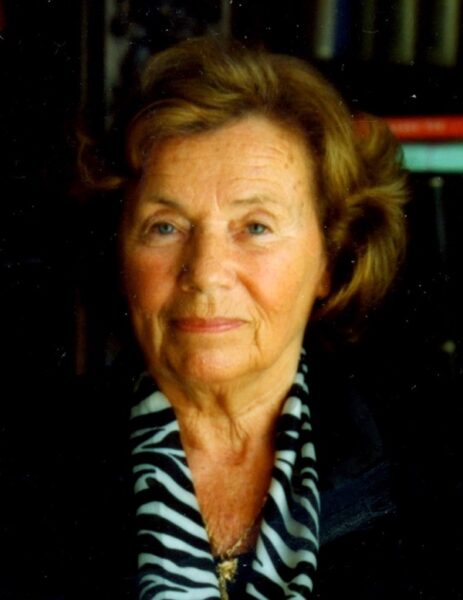

Magda Ádám

Magda Ádám, one of Hungary’s foremost diplomatic historians, died on January 27, 2017. Despite having experienced the past century’s darkest times, she lived a remarkable life of courage, generosity, and professional accomplishment.

Magda was born in a large, close-knit Jewish family in the tiny village of Turi Remety in Subcarpathian Ruthenia, the legendary 4,500-square-mile region ruled by five different states in the 20th century. Her idyllic youth ended abruptly in the spring of 1944, after German troops invaded Hungary. Except for her brother, who had been conscripted into a labor unit, Magda and her entire family were deported to Auschwitz, and only she and two sisters survived captivity as slave laborers.

After liberation, Magda went to Budapest, where she married her childhood sweetheart, György Ádám. Like many returnees, she joined the Communist Party, which had promised protection in the new Hungary, but even before 1956, she had become disillusioned with Soviet control and repression.

Magda was trained at Lóránd Eötvös University in Budapest, where she received her MA and PhD. In 1955, she was appointed to the Institute of History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, where she remained until her retirement.

Magda’s principal focus was on interwar east central Europe, which had been a highly sensitive subject in Hungary before 1956. Not only had the official government line been hostile toward the Western powers, but communist solidarity had restrained Hungarian scholars from critiquing their neighbors’ policies toward each other.

By the time Magda entered the profession, equipped with six languages and a zest for archival research, the political atmosphere had grown less repressive. She quickly moved into the vanguard of Hungarian scholars of the Paris Peace Conference; British, French, and US diplomacy toward east central Europe; the Little Entente; and the minority problems in the region. Magda also braved the regime’s lingering ideological constraints by investigating Hungarian foreign policy in the interwar period, one that shifted between nationalist irredentism and pragmatism.

Scrupulous in weighing evidence and evaluating the existing historiography, Magda became an exceptionally productive historian, producing eight books, among them The Versailles System and Central Europe; 15 edited volumes, including the magisterial 5-volume Documents diplomatiques français sur l’histoire du bassin des carpates; and some 50 articles in Hungarian, French, German, and English on complex issues such as ethnicity and nationalism in the successor states, and the Munich Crisis and Hungary.

Behind her remarkable grasp of the essential details and the larger picture along with her clear and objective prose, there was Magda’s passion for justice: to rehabilitate those who had been maligned by ideologically driven scholars and to revise those who had received undeserved praise based on political motives. Among her numerous scholarly honors were fellowships at St. Hilda’s College, Oxford; the École Pratique des Haute Études in Paris; the Consiglio Nazionale della Ricerche in Rome; and the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, DC.

Magda Ádám was also a master teacher. Beginning in 1983, she began directing a small seminar for advanced students of the Loránd Eötvös University, which, according to one her students, opened their gateway to international history, teaching them to analyze documents in their original language and context, scrutinize every diplomatic actor, recognize the interplay between strong and weak powers, and resist the allure of dogmas.

Magda Ádám was a deeply refined and elegant woman who was also an avid tennis player. Devoted to her family and her friends, she was a graceful conversationalist, displaying wit, wisdom, and compassion. An inveterate traveler, she also loved her large and comfortable apartment in the Buda hills, where she enjoyed preparing delicacies for her students and visitors. Magda’s devotion to her country and its future were eloquently displayed in June 1989, when, at a conference dinner in Washington, she led a toast on the occasion of Imre Nagy’s reburial in Budapest.

Magda is survived by her daughter, grandson, and three great-grandchildren. Her memory will also be cherished by her grateful former students and her friends and colleagues.

László Borhi

Indiana University

Carole Fink

The Ohio State University

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.