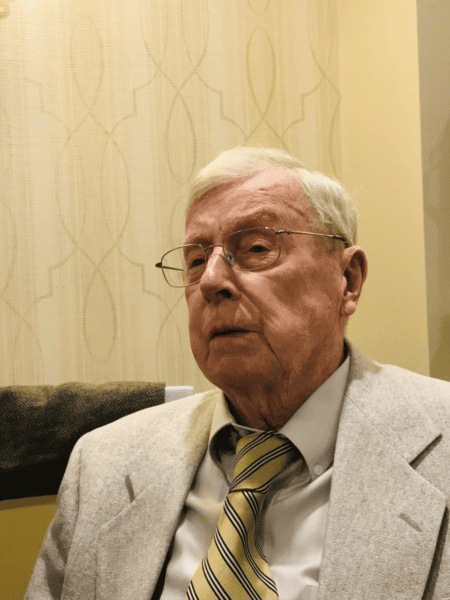

Mack Walker. Photo courtesy Walker family

Mack Walker, one of the most distinguished German historians in the postwar era, died of complications from COVID-19 on February 10, 2021.

Born in 1929 near Springfield, Massachusetts, Walker had the persona of a no-nonsense New Englander. His liberal arts education at Bowdoin College gave his scholarly writing a rich literary quality and a vigorous personal voice. Earning his BA in 1950, he enlisted the next year in the US Army. A tour of duty in southern Germany was a hinge in his life. He began thinking there about the themes of his later scholarship, and he pondered the question that has baffled so many Americans: How could the country with the legacy of Goethe and Schiller, Bach and Beethoven, also have produced the Nazis? In Germany, he also met his beloved wife, Irma.

After returning to the United States, Walker earned a PhD in 1959 at Harvard University, where he worked with William L. Langer and Franklin Ford. He taught at the Rhode Island School of Design for two years, before returning to teach at Harvard. In 1966, he joined the history department at Cornell University. His respect for skilled manual labor found expression in the hard work he and Irma devoted to turning a neglected farmhouse outside Ithaca into a lovely home. In 1969, under the combined heat of antiwar protests and the Civil Rights Movement, Cornell nearly boiled over into a major scene of violence. Mack was one of the few who tried to mediate between the hardline majority among his history colleagues, who opposed the students’ actions, and the progressive minority. It was a thankless task.

In 1974, Walker moved to Johns Hopkins University. There he was among a cohort of early modern Europeanists who shaped generations of graduate students. He was a model of constructive engagement with students’ research and writing, taking their ideas seriously while pushing them to refine arguments and keep details in focus. He retired in 1999.

Walker’s scholarship approached major issues in German history from a variety of productive angles. His first book, Germany and the Emigration, 1816–1885 (Harvard Univ. Press, 1964), anticipated the current emphasis on transnational history by exploring the impact of emigration on German politics. Walker then turned his attention to the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation, which sprawled across western and central Europe until 1806. Arguably, he was unrivaled in his mastery of the political culture and the institutional and legal intricacies of the empire. His second book, German Home Towns: Community, State, and General Estate, 1648–1871 (Cornell Univ. Press, 1971), was hailed immediately as a classic. It told the story of the guild artisans, at once democratic, hierarchical, and fiercely exclusive, who operated under the umbrella of a federally constituted empire. His next book, Johann Jakob Moser and the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1981), used the career of one bureaucrat and jurist to map the empire with unprecedented density. Moser anticipated recent trends in biography, using the life as a point of radiation out into an entire world. The Salzburg Transaction: Expulsion and Redemption in Eighteenth-Century Germany (Cornell Univ. Press, 1992) completed Walker’s trilogy on the empire.

Through his work with the AHA’s Conference Group for Central European History (now the Central European History Society), the German Historical Institute in Washington, DC, the Johns Hopkins graduate student exchange program with the University of Bielefeld, and fellowships at the Max Planck Institute for History in Göttingen and the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin, Walker contributed to the evolution of history as a discipline in West Germany and to transatlantic cooperation among historians. He was quick to spot academic sham and pretense, perhaps because integrity seemed to have been hewn into him, although it was casual, without self-righteousness. Despite his brusque Yankee manner, he was caring and kind to students and colleagues.

Mack Walker was not simply a uniquely gifted scholar; he was a person of singular character. In addition to his wife Irma, his children Barbara, Gilbert, and Benjamin and five grandchildren survive him.

Anthony LaVopa

North Carolina State University (emeritus)

Tanya Kevorkian

Millersville University

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.