A colleague of ours teaches an introductory geography course. Much of its early content deals with ocean currents, and he informs his class that the first exam will contain a map exercise in which students will have to draw the major Pacific and Atlantic currents, briefly describe their essential physical features, and explain their primary effects. After one such exam a half-dozen distressed undergraduates clustered around his desk to complain about the “unfair” map question. “What,” he asked in genuine bewilderment, “was unfair? I told you there would be a map question. I even told you exactly what you would have to know in order to answer it.” “No,” they replied. “you only told us we had to be able to draw the currents and describe them.” “So,” he said, “that’s just what I asked. I even labelled all the continents on the map.” “That’s just it,” the students said. “You labelled the continents, but not the oceans.”

How could students living in Massachusetts, several for all of their lives, be unable to find the Atlantic? Our colleague asked them just this. Their reply is worth pondering. “We didn’t know that we had to know it for the test,” they explained. They had studied what they knew they had to know and, presumably, nothing else. Further, we hypothesize, they were so used to dealing with course work in terms of information that they had difficulty figuring out where the Atlantic Ocean was on a standard two-dimensional world map. They could not, for example, find Massachusetts even though North America was clearly marked. If they could have done so, at least those who summered on Cape Cod might have been able to infer the Atlantic’s location.

This story has at least three morals: students do have amazing gaps in their fund of knowledge; these gaps can incapacitate (i.e., it does one no good to know all about ocean currents if one cannot find the ocean); a teacher’s emphasis upon the mastery of information may as often cause as cure these gaps.

Information overload is the all-too-common, if ironic, outcome of such an emphasis. Carrie Foster and Connie Rickert-Epstein provide a useful description in their review of college textbooks in The History Teacher 22:46: ”Beginning students are frequently overwhelmed by an inundation of facts—who, what, when, where, why, how. They panic and flounder accordingly, convinced early on that there is no way to assemble these facts and gain mastery over them.” Overload is a problem endemic to introductory-level and other survey courses. Virtually all seek to “cover” large amounts of material. In the process they introduce very large quantities of information, at least some of which instructors expect students to remember and even understand. Students often see matters differently. They define their own tasks within such courses in terms of this flood of information. The courses become, for them, exercises in the “quick recall of specific fact,” to use the phrase of the old “College Bowl” television program. This, of course, is rarely if ever the primary emphasis of instructors, who are frequently frustrated by how little understanding of factual material students dis play. More distressing still is our awareness that within a few months many students will have for gotten most of the information they labored so intensely to memorize. Worst of all is the certainty that instructors will receive the blame when these same students prove unable to place the American Civil War in the correct century or to distinguish “Churchill’s words from Stalin’s,” to use two examples cited by National Endowment for the Humanities Chair Lynne V. Cheney in her 1989 report, 50 Hours: A Core Curriculum for College Students.

This student proclivity to define introductory courses in terms of their own informational content has yet another unhappy consequence. Stu dents tend to reduce those portions of the course intended to introduce them to the classic issues in the discipline to exercises in information mastery as well. So, for example, they treat a question about the consequences of the 1820 Missouri Compromise in the same way they treat one concerning the provisions of the Compromise. The second of these questions actually is a matter of information retrieval, but the first involves interpretation; it cannot yield a single, definitive answer. However, students often treat it as though their task were to compile a list of consequences, drawn from the textbook, and then to commit the list to memory.

When the history department at Assumption College decided to create a new introductory course combining western European and American history since 1450, we were deeply concerned with these issues. We knew that, regardless of what particular topics our course included, it would be rich in information. We knew too that the college’s new core requirement in history presumed as much. And we were convinced that some historical information is well worth knowing. We did, that is, want students to know what the Edict of Nantes was and what role Otto von Bismarck played in German unification. As Cheney sardonically noted in 50 Hours, “students who approach the end of their college years without knowing the basic landmarks of history and thought are unlikely to have reflected upon their meaning.” However, as she also argued, “education aims at more than acquaintance with dates and places, names and titles.”

We wanted our students to be familiar with some of the classic problems in the historical study of the West so they could discuss the causes of religious turmoil in the sixteenth century as well as identify the Edict of Nantes, analyze the sources of nineteenth-century nationalist movements as well as know who Bismarck was. We did not want them to turn standard answers to these problems, as found in textbooks, into lists of “factors” to be memorized as though they were so many provisions of a treaty. We did not want them, in short, to be able to map the currents but be unable to find the ocean.

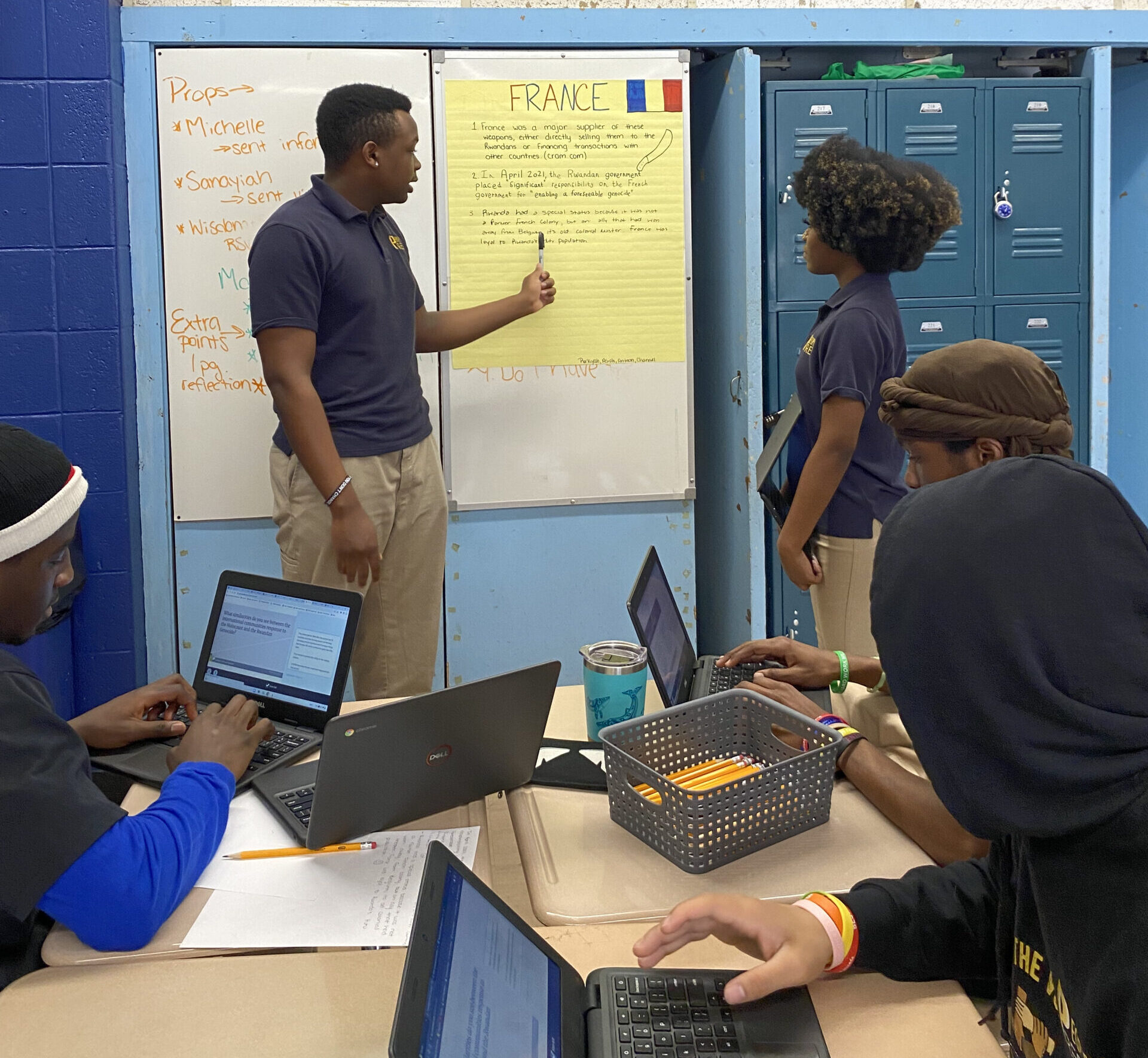

Our experience with freshman students demonstrates that, even in courses with oceans of facts, it is nonetheless possible to engage them in a dialogue over what information is important, why it is important, and how practitioners in the discipline define satisfactory answers to such questions. One approach we have adopted has worked well enough to make it of potential general interest. At its heart is a weekly exercise in which our students select eight specific events germane to the course material then being covered and write a single paragraph for each. Arguing for the centrality of that particular event for understanding either that week’s material or the course as a whole. The idea is to have them use information in a historically meaningful way. We chose for them to argue for eight events, rather than seven or nine, say, so that when combined with an opening and a closing event chosen by us, the number of events discussed adds up to ten. The actual number is unimportant, provided that it is small enough for students to complete the assignment. Moreover, the fundamentally arbitrary character of choosing any number can itself serve useful pedagogical ends—as we shall argue further.

We devote a full class session each week to a debate over which of the twenty-five or thirty events proposed by the students are most “crucial” to grasping the central themes of the course. We provide students in advance with a brief written discussion of six or so themes for each unit of the course, and we supplement them with a set of “focus questions” students can use while working their way through that week’s assigned primary and secondary materials. In our unit concerning ‘The Political Response to Change: Reaction, Reform, and Revolution, 1815–1848,” for instance, one theme defines why we chose the Congress of Vienna as our opening event. “Led by men like Prince Klemens von Metternich of Austria, conservatives sought to capitalize upon their victory in the Napoleonic Wars to restore the prerevolutionary political system (the ‘Ancien Regime’), to revive aristocratic and clerical privilege, and to resist middle-class demands for greater power. The Congress of Vienna (1815) saw a formal beginning of this campaign.” Our focus questions similarily seek to highlight central themes of the course by suggesting to students what it is they should be reading. One for this same unit asks: ”In what ways did nationalist aspirations become entwined with liberal demands before 1848?” We instruct students to “indicate in your own words (no paraphrases of secondary materials allowed) why the particular event in question is crucial to the story. Use the unit themes and focus questions as guides to what this unit’s story is. Each event you choose should normally relate to one or another of these themes and questions.”

Unit themes constrain but do not coerce stu dent choice in selecting events. This means we cannot guarantee in advance what students will nominate, but we do define the set of possible events from which they will make their selections.

The eight for which (in the instructor’s view) the most cogent arguments have been made are placed, along with the opening and closing events we chose, onto a master list of “crucial events” that we compile week by week. At the end of the semester we test our students’ understanding of the events on the master list by selecting twenty-five and asking students to write a paragraph for each, arguing for its importance in terms of the central themes of our course. The score on this quiz constitutes one-tenth of their semester grade.

The students are also graded on this exercise each week, and their averaged weekly score constitutes another one-tenth of their total grade. We grade each paragraph of argumentation on its own merits, whether or not the event concerned has been selected for the master list. We keep a separate tally of the number of times a student’s proposed “crucial event” makes it onto the master list. The student with the highest number of successful nominations is awarded an automatic 100 for the quiz at semester’s end and exempted from having to take it. This element of competition and reward adds considerably to the zest with which students argue each week for the importance of the events they have selected.

In all, the “crucial events” component of our course constitutes one-fifth of a student’s grade. A weekly written exercise on primary materials counts for another tenth. Three interpretive es says combine for another two-fifths. The remaining 30 percent reflects a joint evaluation by student and instructor of the student’s preparation for, and participation in, class discussions. Our aim is for “crucial events” to count for just enough for students to take them seriously.

A key goal is to force students beyond their repertoire of information retrieval techniques. They cannot succeed by simply describing an event. They must explain why it is important. And they cannot simply rehearse the textbook’s analysis, since we insist they make their case for an event’s centrality in terms of our course’s themes.

Sometimes the textbook discussion will bear directly upon our themes and questions, and when it does, students happily parrot it. Fortunately, this strategy of getting the textbook authors to ghostwrite one’s assignment only works about half the time; students realize they cannot afford a string of 50s if they want to pass. So they are forced into reading the textbook and other secondary works more critically and selecting from them only material that actually bears upon the task at hand. We insist in our syllabus that “the course is not designed to follow any particular textbook in a chapter sequence. You should think of your textbook as a reference work.” We also seek in our unit themes to make students aware of competing schools of historical interpretation; and we encourage them to notice the tendency of textbook authors to seek safe and non-controversial formulations. It is the exercise itself, however, which does the most to bring these ideas home to students because it systematically refuses to reward them for simply locating information or rehashing judgments, in short for being uncritical readers.

Our “crucial events” approach is based, albeit loosely, upon the work of David Perkins, a cognitive psychologist at the Harvard School of Education. Perkins distinguishes four thinking “frames” that practitioners employ and students encounter in any discipline. One is “informational” thinking, the body of fact without reference to which one cannot do any work. One must know, for example, when the French Revolution began if one is to have any chance of understanding the way historians seek to explain it. A second frame Perkins calls “problem-solving.” What he means is familiarity with the classic problems in a discipline, such as why the Industrial Revolution began in Great Britain. Discourse among historians is largely organized around such core questions and around the issue of whether some new or previously undervalued set of questions ought to attain canonical status. Perkins’ third frame is the “epistemic.” This refers to the ways of evaluating and explaining peculiar to each discipline, such as periodization in history. Finally, there is “independent inquiry,” not usually a goal, and properly not, of introductory courses.

We found this typology of frames helpful in thinking about what we wanted our students to do and in describing what they most often did in stead. Specifically, it helped us see how readily students transform problem-solving tasks into in formational ones by, for example, treating the causes of the English Civil War as a list of five or six discrete facts. This is their default mode, to use a computer analogy. Further, Perkins’ theory gave us an insight into the ways in which we sanction such student reductionism even as we bemoan it. What had actually happened in our courses, the theory encouraged us to ask, when students supplied informational answers to problem-solving or epistemic questions? The fact was that we had let such answers pass. We did not give As or Bs for them, but we did give Cs or C+s. And for the many students who did not expect to do A work in the first place, this was good enough.

Our “crucial events” assignment is designed to change their behavior—and ours. It requires students to formulate arguments rather than simply compile information. These arguments must relate specific pieces of information to classic problems in the discipline, what Perkins calls problem-solving. And it also requires students to use historical patterns of explanation and argumentation. This is Perkins’ epistemic “frame.”

The assignment requires us to change grading practices. We grade each paragraph on whether it fulfills the assignment. If it does, the student receives full credit even if the paragraph includes a minor factual error or two. (Gross factual mistakes invalidate a paragraph no matter how cogent its argument) If the paragraph does not show the event’s relevance for our course, the student receives no credit. There is no middle between these two outcomes, no way for us to “reward” the student who compiles a lot of information but fails to make a case for its salience.

Despite the importance it attaches to historical analysis, the exercise does not seek to downplay the importance of information. It does not entail a trade-off between “content” and “process.” Instead, it insists that historical information only makes sense in terms of historical questions and styles of analysis.

Making students choose and argue for the crucial importance of particular events has the further benefit of forcing them to think about how the course fits together. This is what we meant when we said that the very arbitrariness of forcing students to choose eight events had pedagogical value. It is immediately apparent to students that there are innumerable events for which arguments might be made. The necessity of nonetheless choosing eight, and only eight, makes them compare events and hypothesize some relation ship among them. Otherwise they find themselves unable to argue why one should be considered more important than another. The fact that they inevitably disagree, and that their grade depends not upon selecting the “right” event but upon the cogency of their argument for their choice, highlights for them the crucial role of interpretation in organizing and making sense of information.

This effect emerges with special clarity in student course evaluations. More than half (51.5 percent) cited the crucial events assignment as the “greatest strength” of the course. One student commented: “These make you think and concentrate on what you read. It helps you to understand the significance of the event and the time period.” Another said of the assignment “(it) makes the class unique and interesting, and keeps yo? honest as to whether or not you are really doing the reading.” A third wrote that the crucial events make “us go through the reading, and pick out the most important people and events to write about. Though this is a long process, you don’t forget the crucial events once you’ve done them.”

Students also have complaints, especially about the amount of work required to complete this and a second weekly writing assignment (on primary materials). They also complain about the difficulty of the assignments. What is gratifying is the large number of them who see the direct connection between work and learning. As one student put it, “because there is so much work and required reading, you can’t do nothing in this class. Therefore, everyone must learn something.”

Indeed, students learn much in the course starting with a good deal of information. One measure of this is their performance on the final quiz. Most do very well, and very few make the sort of bonehead mistakes (confusing Henry IV of France with Henry VIII of England, say) that makes instructors wonder if anything they said penetrated.

A related test comes in the three interpretive essays they must write over the course of the semester. These do not require students to recall specific events but to find relevant information to support their analyses. Their initial efforts, turned in a month or so into the course, show only the most rudimentary understanding of the historians’ responsibility to support their interpretations with relevant evidence. By their third essays, handed in at semester’s end, virtually all students have learned to provide specific examples of their main points, and a healthy minority have begun to develop a measure of real sophistication in the use of historical information.

Students also learn much about the classic problems of causation, periodization, and influence that largely define historical discourse, because the course themes, to which they must relate their crucial events, bear upon just these is sues. Further, because they must construct arguments rather than simply describe events, they receive regular practice in what Perkins calls the “epistemic” dimension of historical study.

Finally, students, despite complaints about the amount of material covered, do not feel lost, overwhelmed, or inundated. Quite the contrary. As one wrote, “I was able to get a feel for how the world today came about from things and happenings of the past.” A second common response emphasized: ”The greatest strength is that this course makes you think about what is being taught.” A third student also spoke for many: “The crucial events helped me evaluate my studies Even though the course was difficult, I can honestly say I learned the most in this course.”

John F. McClymer and Paul R. Ziegler teach history at Assumption College. An earlier version of this essay was presented at the Ninth Lilly Conference on College Teaching, November 1989. The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of colleagues Kenneth J. Moynihan, Raymond J. Marion, and Louis Silveri. The development of this course was underwritten in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.