On Friday, June 6, 2025, demonstrators took to the streets of Los Angeles to protest the recent Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids targeting undocumented immigrants. The protests began peacefully, with crowds gathering to rally against the government’s aggressive tactics. But as night fell, the scene shifted. Groups of mostly young, non-Mexican antifascist protesters smashed walls, looted local businesses, and vandalized cars. The next day, raids continued throughout Los Angeles County, and the unrest spread and escalated, reaching Compton, located 15 miles south of downtown Los Angeles. Amid the chaos, photojournalists, YouTubers, and TikTok influencers filmed the fiery scenes. The resulting images captured global attention, showing burning buildings, shattered windows, motorcycle riders around a burning car, and a Mexican flag waving through the smoke.

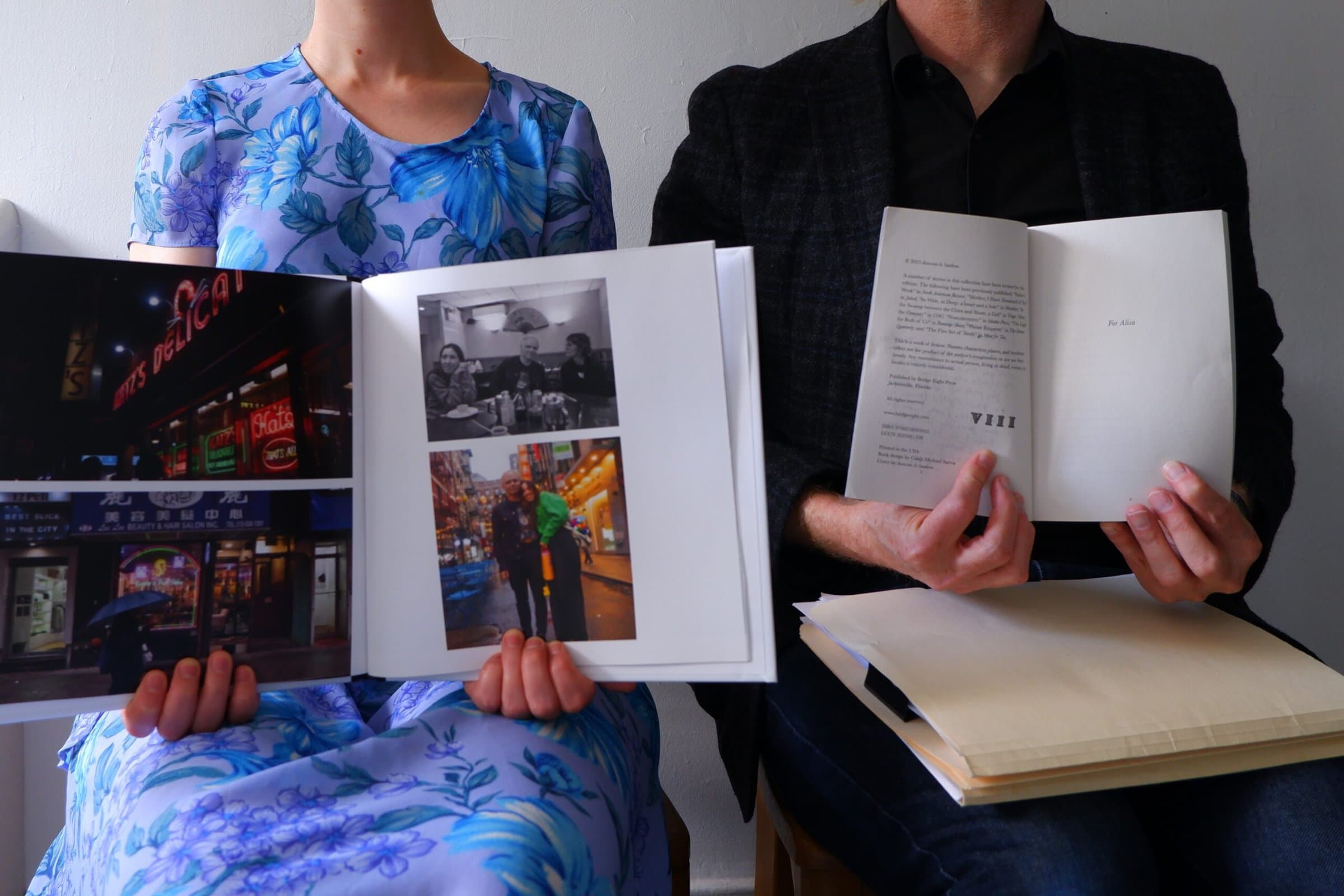

The Catholic identity of Mexican and Mexican Americans infused the protests against immigration raids in summer 2025. Courtesy José Luis Castro Padilla

ICE raids have continued throughout the summer across cities in Los Angeles County and beyond, reaching into towns with significant Hispanic populations as far north as Ventura County, where many ethnic Mexican farmworkers live and work. These operations have been aggressive and indiscriminate. People detained in Home Depot parking lots, at bus stops, and while buying coffee are mostly brown and Hispanic, including legal residents and US citizens. These raids are not simply recent events but reflect a deeper historical pattern of social injustice against ethnic Mexicans in Southern California.

These aggressive government actions are not isolated incidents. For more than a century, this community has been scapegoated, segregated, and pushed to the margins of American society. Yet amid this oppression, progressive Catholic voices have at times offered a powerful counternarrative, one that champions dignity over forced assimilation and honors culture instead of erasing it. Given that most ethnic Mexicans identify as Catholic, it is crucial to examine how non-Hispanic Catholic activists have supported and fought for immigrant communities in Los Angeles. This long-standing solidarity between Catholic activists and immigrant communities is now being tested, as even churches, once considered sanctuaries, are no longer immune to the reach of immigration enforcement.

The Mexican American community is unified not only by heritage but by a shared experience of marginalization in their own country that stretches over the last century. Since 1910, when immigrants first fled the violence of the Mexican Revolution and arrived in Los Angeles, they entered a city that had already seen its original Mexican population become a minority due to mass migration from the east after the Civil War. New arrivals found a city that spoke a different language, practiced a different religion, and often met them with hostility. Yet the predominantly Catholic Mexican community played a vital role in growing the local church, helping it become the largest Catholic diocese in the United States.

Progressive Catholic voices have at times offered a powerful counternarrative, one that champions dignity over forced assimilation and honors culture instead of erasing it.

Yet by 1919, Bishop Joseph J. Cantwell of the Diocese of Monterey–Los Angeles launched an Americanization campaign, pressuring ethnic Mexican Catholics to abandon their language and cultural traditions in favor of English and assimilation. Some white Catholics opposed his approach, including activist Mary J. Workman, who insisted that true integration should come not through cultural erasure but by showing immigrants the promise of American life and encouraging them to pursue it through shared Christian values. For Workman, Americanization wasn’t about erasing identity but fostering mutual understanding, encouraging immigrants to learn American values while also sharing their own rich traditions. She championed the right to speak Spanish and celebrate Mexican culture—both at home and within the church—including Indigenous forms of honoring saints, a practice the local diocese often rejected.

Like Workman, Father Thomas J. O’Dwyer offered a vision of integration rooted in dignity and cultural respect. In the National Conference of Catholic Charities, O’Dwyer argued that Mexican immigrants did not abandon their identity at the border; instead, they brought with them a vibrant culture—fiestas, music, dancing, and the cherished tradition of sharing coffee and conversation on the sidewalk. Their arrival also marked the strengthening of a deep sense of community and brotherhood.

O’Dwyer and Workman witnessed firsthand the harsh realities these immigrants faced: meager wages, overcrowded and substandard housing, segregated schools with inadequate resources, and authorities who routinely ignored their rights. Yet Mexicans came in pursuit of happiness. Their children, born in this land, may grow up indifferent to the injustices their parents faced. But the foundation their parents laid by working hard and adapting to hardship spoke volumes.

In the 1930s, President Herbert Hoover’s administration turned Mexicans into convenient scapegoats for the economic collapse of the Great Depression, resulting in the mass deportation of over a million people, many of them US citizens. It is a period where racial segregation shaped both housing and education, forcing Mexican immigrants to live in slums under deplorable conditions and sending their children to separate schools. These schools operated with underqualified teachers and poorly equipped facilities. It was not until 1945 when a legal battle over school segregation reached the desk of federal judge Paul J. McCormick, a Catholic layman, in Los Angeles. The ruling in Mendez v. Westminster (1947) marked a critical step toward desegregation, but it did little to dismantle the persistent discrimination Hispanic students faced in Los Angeles schools.

Young Chicano activists organized, raised their voices, and stood in solidarity, demonstrating that resistance could be heard. By 1968, amid national civil unrest, Chicano students marched through the streets of East Los Angeles to demand educational reform. They protested policies that banned Spanish in classrooms and funneled Mexican American students into curricula meant for those with learning disabilities. Instead of addressing these injustices, the government responded with violence, leading to the arrest of at least 13 organizers. Meanwhile, the church hierarchy remained silent. On Christmas Eve 1969, a group of young activists, the Catolicos por la Raza, gathered outside St. Basil’s Church, condemning the church’s lack of support for the farmworker movement led by Cesar Chavez and its indifference toward the Chicano student walkouts.

These young Catholics demanded the clergy’s support because Catholicism holds deep importance in the Mexican community, intertwined into cultural identity and values across generations. Yet, these same values were gravely violated in the 1970s, when unauthorized sterilizations were performed on Mexican women at the Los Angeles County–USC Medical Center. Ten women came forward to sue the hospital, but in 1978, the United States District Court of the Central District Court of California ruled in favor of the institution, citing that the women had signed consent forms—forms written in English, a language they did not understand. These women, stripped of their reproductive rights without true consent, became victims of a system that failed to protect them.

Although the church hierarchy neglected to support its community, Hispanic Catholic priests began to get involved in social struggles. In the 1980s, influenced by the liberation theology, Father Luis Olivares led the sanctuary movement in Los Angeles from the historic Placita Church. According to historian Mario T. Garcia, Catholic activist and priest Richard Estrada recalled, “Olivares, by listening to the refugees, in a sense became a refugee himself, or at least envisioned himself as one, to better appreciate what he was hearing.” Father Olivares inspired Father Estrada’s own activism. Until his death on March 31 of this year, Father Estrada was a passionate advocate for the immigrant community, including LGBTQ+ migrant rights, and continued the tradition of social justice rooted in faith and solidarity.

Those holding the Mexican flag during demonstrations in Los Angeles are young people tired of the systematic abuse we have suffered throughout the history of this city.

After years of social injustice and adversity, today’s Mexican Americans enlist in the military, contribute to this country, have families, participate in Catholic communities, and are proud to be American, but we are also proud of our Mexican roots and culture. Those holding the Mexican flag during demonstrations in Los Angeles are young people tired of the systematic abuse we have suffered throughout the history of this city, and the flag represents not only pride in their place of origin but also discontent in a system that has failed us. Historically, profound social inequalities in education, healthcare, and employment have confined ethnic Mexicans to the bottom of the social ladder, reducing us to the stereotype of cheap labor. Today, these injustices go hand-in-hand with the fear of going to work, attending school, even church, and being kidnapped by ICE and never seeing our family again.

The City of Angels has failed the Latino community, and they demand to be seen, heard, and treated with dignity. The Catholic dioceses in southern California have announced assistance for families affected by ICE raids and aid with immigration court appearances. On the streets, interfaith organizations such as LA Voice, formed by the Catholic Church and Evangelical, Methodist, Muslim, and other religious communities, are joining the peaceful protests. Sadly, as long as the raids and arrests continue in our Latino communities, the churches will remain nearly empty. The hope of finding peace and returning to normal life remains present on the streets of this city.

José Luis Castro Padilla is a PhD student in Chicano/a and Central American studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. As a historian, he focuses on Catholicism in Mexican immigrant and Mexican American communities of California.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.