The Scottsville Museum is housed in an 1846 building that was formerly a Disciples of Christ church. Courtesy of Connie Geary, Scottsville Museum.

As a historian of medieval cartography, I thought the last thing I would ever do was get involved with the local museum in my town, Scottsville, Virginia. Many small towns have one: a museum of local history founded by patriotic citizens and run on a shoestring by a legion of unpaid volunteers. Having studiously avoided American history in college and graduate school, I knew myself to be supremely unqualified. But my neighbors felt differently. Often I’ve heard, “You’re a history teacher; why don’t you join the museum board?” Or, even more confounding, “Why don’t you join the United Daughters of the Confederacy?” Finally, on retirement, I had run out of excuses. So a few years ago I found myself president of the board of trustees of the Scottsville Museum.

Scottsville, a town on the James River founded in 1744, started its museum in 1969 in a Disciples of Christ church (1846) whose congregation had melted away. It is a beautiful building, located on a steep hillside with several flights of brick steps leading up to it. But since it is a listed building, it has proved impossible to retrofit for people with disabilities. Other small towns have other historic buildings suitable for museums: the jail (no longer in use), the school (long since consolidated into a larger one), or a historic house (willed to the town by its owner). These are wonderful artifacts in themselves but come with a burden of expenses for repair and modernization (air conditioning, electric outlets, plumbing, wireless).

Our museum, while a great source for local history, has a few problems. I won’t go into the joys of fundraising, the roof repairs, the search for grants, the management of wonderful but sometimes unreliable volunteers. I will instead focus on three issues: objects, objectivity, and small museums as resources for historians.

Material objects, or stuff. Small-town museums are the targets of numerous bequests. We receive the contents of neighborhood basements and attics; at the Scottsville Museum, recent examples include a vase once belonging to Edith Bolling Wilson, a framed certificate presented to the winner of a high school essay contest (1935), a spy novel by a deceased resident, the post office window and boxes from a nearby defunct town, a butter mold, a chair made by a former slave, a paperweight made out of a World War I shell casing, and a button from Robert E. Lee’s uniform turned into a bracelet. How to make a coherent exhibit out of all this? And how do we preserve and store it? And how do we catalog it so we know what we have and can find it again? We seldom purchase anything, though occasionally a devoted board member will buy something. Many of our exhibits consist of loans, the advantage of which is that they return to their owners when the exhibit closes.

Because our collection comes from residents, their sharp eyes watch what we do. Why isn’t my great-grandmother’s ostrich feather fan on display? Or, I’ve changed my mind—I want Great-Uncle George’s Confederate flag back. We do sometimes turn things down—regretfully, a floor-length raccoon coat, which we knew we would never be able to store properly. And yet another World War II uniform.

No matter how informative the texts one mounts on the wall, people come to museums to see stuff. Letting schoolchildren pass a Native American spearhead from hand to hand is far more riveting than seeing it behind glass (“Wow! It’s sharp!”) and way more interesting than reading about it. So we definitely need our stuff, although it takes considerable ingenuity to manage it.

Objectivity. As historians, we are trained to deal with the facts as objectively as possible, trying not to inject our personal opinions or prejudices. While this is hard enough to do when studying the Middle Ages, it is much more challenging when the history is local. Our town has had its share of problems, including slavery, racial tensions, civic disputes, family feuds, adulterous relationships, even a few murders, embezzlement, and arson. There are many silences. When putting together an exhibit on World War II (Small Town/Big War), I found information about a local man serving in North Africa who had received a medal for heroically rescuing a comrade under fire. When I tried to include him in our show, I was told, “We don’t talk about him. He met up with some German fräulein and never returned to his wife and children.” Oops. At a board meeting, when we were discussing the history of race relations, one of our members exclaimed, “I don’t want to hear anyone running down Scottsville! Our job is to promote our town.” Is that it? The Smithsonian thinks it has problems!

Recently, Scottsville came in for its small share in the Virginia Sesquicentennial of the Civil War. Although many of our citizens served in the Confederate army, war did not come to Scottsville physically until March 6, 1865. General Philip Sheridan, having defeated Jubal Early in Waynesboro, crossed the mountains and marched east along the James River, destroying railroads and the James River and Kanawha Canal. Once in town, the army commandeered food, livestock, and other movable goods, and set fire to warehouses and factories. Then the soldiers marched out, followed by a significant number of slaves, and leaving a smoldering scene of destruction behind.1 So how does one celebrate a raid? We formed a committee in late 2013 to think about this. One of our members got in touch with a troop of Union cavalry reenactors and invited them to ride into town on the anniversary. While generally greeted as an exciting idea, the prospect of being invaded once again by the dam’ Yankees raised the ire of certain unreconstructed Confederates. We received some hate mail. Our argument, that this was our history, was not convincing to everyone. The irony was that in late February and early March of 2015 the eastern part of the country was visited by snowfalls, especially Pennsylvania, from whence our cavalry was to come, and the march was canceled. We were left with the other events we had planned: the Virginia HistoryMobile (a traveling Civil War museum), a refurbished museum exhibit, a walking tour of Civil War sites in town, and a program of lectures on different aspects of the war. Included in this program were two talks on the African American population during and immediately after the war.2 A local group of Confederate reenactors was happy to set up shop across from the museum and go through its paces.

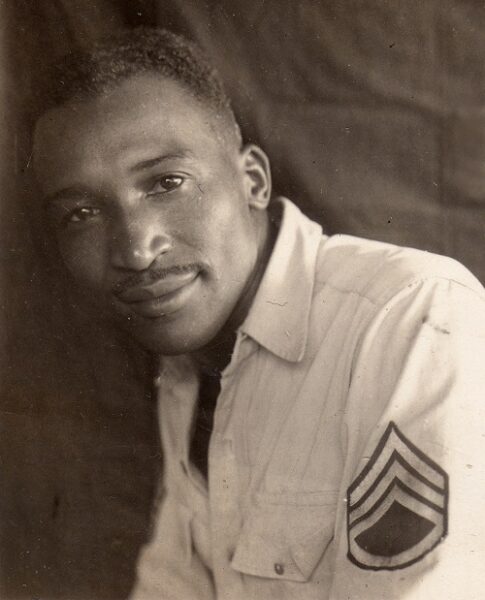

Scottsville resident Allen C. Gooden, staff sergeant in the US Army Air Corps from 1942 to 1946. From the Scottsville Museum exhibit Small Town/Big War: Scottsville in World War II

Resources. Small-town museums are treasure troves of information and artifacts seldom used by academic historians. Our 2006 exhibit Small Town/Big War was based on almost 100 oral history interviews with local veterans. Ten percent of our town population served in the war, and some, who probably would have traveled no farther than Richmond, Virginia, in their lifetimes, found themselves in New Guinea, Japan, Italy, and on the beaches of Normandy. I have recently read several laments on the passing of World War II veterans with their history unrecorded. I am sure Scottsville is not alone in collecting this material. We also interviewed women, children, industrial workers, and other noncombatants about conditions on the home front.3 One woman, in the absence of her husband, took over the family farm. “My husband said he worried more about me driving the tractor on those steep slopes than he did about himself facing enemy fire in Italy,” she told us.

These reminiscences—listening to the radio, planting a Victory Garden, hoarding ration stamps, waiting for letters on transparent V-mail stationery—give texture to the wartime lives of our citizens. We reconstructed a 1940s kitchen in a corner of the museum. It stopped some visitors in their tracks. Seeing the “Hoosier” cabinet, the oilcloth-covered table, the flap-open toaster, they exclaimed, “It’s just like my grandmother’s kitchen!”

From the lofty vantage point of my new career as a public historian, I urge my colleagues to use our small-town museums as a resource, both for yourselves and for your students. You may be surprised at what you find.

Notes

1. Richard Nicholas, Sheridan’s James River Campaign of 1865 through Central Virginia (Charlottesville, VA: Historic Albemarle, 2012). Copies available from the Scottsville Museum.

2. Regina Rush, “The Rushes of Chestnut Grove: One Family’s Journey from Slavery to Freedom,” Scottsville Museum Newsletter, no. 25 (Spring 2015): 4–8.

3. Including John R. McNeill, “Veterans and Remembrance: Before It’s Too Late,” Perspectives on History, October 2012. For texts and pictures of the World War II interviews, go to the Scottsville Museum website: scottsvillemuseum.org.

Evelyn Edson is professor emerita of history at Piedmont Virginia Community College. She is author of several books on medieval cartography, including The World Map, 1300–1492: The Persistence of Tradition and Transformation (Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2007) and Mapping Time and Space: How Medieval Mapmakers Viewed Their World (British Library, 1997). You can visit the Scottsville Museum online at scottsvillemuseum.org.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.