Bibliophiles who see Greta Gerwig’s 2019 film adaptation of Little Women by Louisa May Alcott will have ample reason to drool. Aunt March’s house is filled with books in period-appropriate bindings. Jo March (played by Saoirse Ronan) drafts her manuscripts in a marbled-cover journal identical to an original owned by Alcott. A first edition of the novel stands in for the title card.

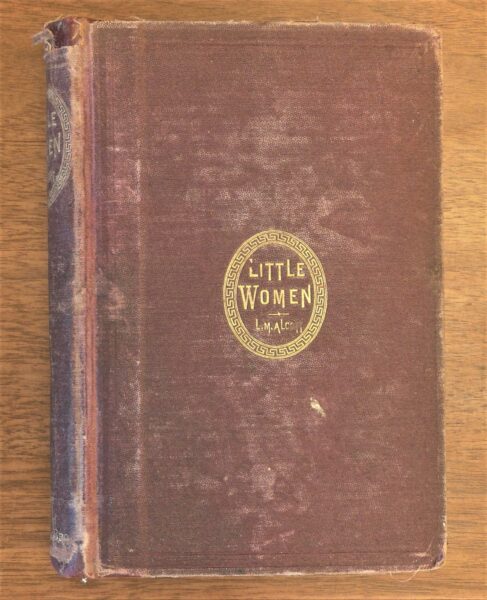

A first edition of Little Women shows just how closely the film hewed to the real production of the book. Louisa May Alcott, Little Women. AC85.Aℓ194L.1868 pt.1 (A), Houghton Library, Harvard University (printed with permission)

Gerwig’s love for the novel is evinced at the film’s conclusion with a montage of the book’s production. Jo watches from the sidelines as a printer sets her words in type and prints the novel on a beautiful iron handpress. A binder takes the freshly printed signatures and sews them into a text block, rounds and backs the spine with a hammer, and binds the text in red leather. In the final moments of the film, he lovingly stamps the title on the cover in gold: Little Women by Jo March. Brushing off the extra gilt shavings, he hands the first copy to the proud author. Book lovers swoon; the credits roll.

Gerwig’s interest in the novel’s creation extends beyond the physical book to the world of publishers, editors, and even copyright. Readers who haven’t seen Little Women may wonder at a Hollywood film that would let such dry topics take up valuable screen time, but the results are surprisingly cinematic. It’s thrilling to see the historic Roberts Brothers publishing house richly imagined in the film’s first scene and to watch Jo spar with her editor over the rights to her novel and its ending. In these scenes, Gerwig references Alcott’s own experience bringing out her novel in the competitive 19th-century American literary market. In fact, Gerwig has stated in multiple interviews that she drew inspiration from both the novel and Alcott’s life, creating a meta-narrative of a novel that is already quite self-referential. In many ways, Alcott’s road to publishing was more extraordinary than Jo’s, and it’s worth unpacking Gerwig’s decisions, which draw from the literary experiences of the two women.

In 1867, Thomas Niles of Roberts Brothers wrote to Alcott encouraging her to write a “girl’s book.” At the time, Alcott wasn’t an obvious choice for a marketable children’s author. Though she had recently assumed the role of children’s magazine editor, she was best known for Hospital Sketches, an epistolary account of her experience as a volunteer nurse in the Civil War. (Mr. March goes off to war in Little Women, but Alcott was actually the veteran of her family.) The path from death and disease to popovers and petticoats can’t have been readily apparent to anyone—least of all to Alcott herself; unlike Ronan’s determined Jo, marching with bluster into her publisher’s office, Alcott initially balked at Niles’s suggestion.

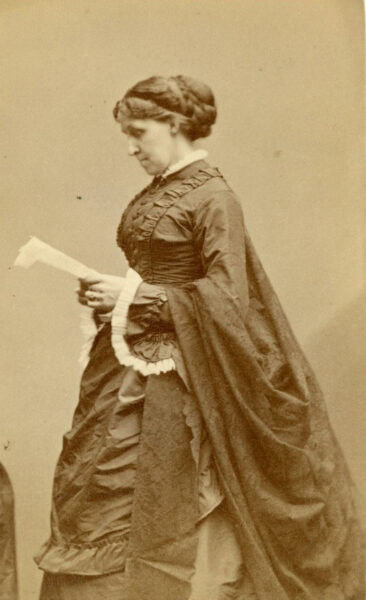

In 1867, Alcott wasn’t an obvious choice for a marketable children’s author.

Moreover, betting on a budding author like Alcott was especially risky in this period of American publishing. Publishers in the 19th century were also booksellers, printers, and distributors, and as a result, they had considerable overhead costs. To generate capital, many American publishers churned out pirated editions of popular British novels, such as those by Charles Dickens or Wilkie Collins, to whom the firms did not have to pay any royalties. (The United States did not recognize the rights of foreign creators to their works until the shockingly late date of 1891.) Most successful publishing houses used these easily gained profits to subsidize risks on new American authors like Alcott.

However, Alcott’s publisher, Roberts Brothers, forged a different path to solvency. Founded in Boston by bookbinder Lewis A. Roberts and his two younger brothers in 1857, the firm made its profits selling photograph albums, which were wildly popular among soldiers and their families after the Civil War. After a few years stockpiling capital, the brothers waded into literary publications and brought Thomas Niles into the fold.

Niles’s foil in the novel and in Gerwig’s adaptation is Mr. Dashwood. Though played with spunk and a twinkle in his eye by Tracy Letts, Dashwood in the film is not half as encouraging and supportive an editor as Niles was to Alcott. Said to have been a “Bostonian by birth and by instinct,” Niles could be found in his cozy rooms at the Roberts Brothers offices at all hours of the day or night, corresponding or chatting with his impressive roster of New England authors. Alcott and Niles wrote to one another often, and much of their correspondence is kept at Harvard University’s Houghton Library. In a letter dated June 16, 1868, one learns that Niles supplied the novel’s title after reading the first completed draft of part one. Niles wrote, “What do you say to this for a title?

Little Women

Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy

The story of their lives

By

Louisa May Alcott”

As a curator at Houghton Library, I love to show this letter to Alcott fans. It reveals a gifted literary publisher at work and also demonstrates Niles’s dedication to Alcott’s work.

In contrast, Gerwig’s Jo must advocate for herself and for her novel before the incredulous and calculating Mr. Dashwood. In a pivotal scene, Jo quarrels with Mr. Dashwood for the copyright to her story and haggles over her percentage of the book’s royalties. Mr. Dashwood insists she won’t see a cent until his costs of producing the book are recouped. This system of payment was known as the “half-profits system,” and many American authors suffered under it for the better part of the century. In reality, Niles was honest to a fault with his authors and paid them fairly for their work. In fact, Niles encouraged Louisa May Alcott to keep the copyright to Little Women. Writing in her journal, Alcott described the two of them as “an honest publisher and a lucky author, for the copyright made her fortune”—more than $200,000 over the course of her life.

Carte de visite of Louisa May Alcott. Louisa May Alcott. Portrait File, Houghton Library, Harvard University (printed with permission))

Considering the Roberts Brothers’ partnership with Alcott and its contribution to the American literary canon, it is a little painful for this Bostonian to see Gerwig move the publisher to New York City. While audiences may be quicker to recognize New York as the literary capital of the United States, Boston was indisputably the center of American literary publishing in the second half of the 19th century. (Curiously, Jo’s publisher is also moved to New York in the 1994 film adaptation. Adding insult to injury, Jo’s novel in that film is published by James T. Fields, a man who once told Alcott: “Stick to your teaching; you can’t write.”) Because Jo’s publisher is never named in the novel, Gerwig’s decision to grant Roberts Brothers a starring role in the film reads as a deliberate and affectionate homage. However, by making Jo fight for her story, her compensation, and the ownership of Little Women’s copyright, Gerwig ensures that Jo’s success belongs solely to her. If these elements eschew Alcott’s experience, they do right by Jo March. To underscore Jo’s pride in her success as an author, Gerwig ends the film not with a promise of marriage (over which a lot of ink has been spilled) or with the rosy family garden party at Plumfield, but with Jo holding the first printed copy of Little Women in her hands.

This ending and the printing montage that precedes it are heart-stirring. However, despite the romance of the scene, it caused some consternation among librarians and book historians (mainly, benignly, on Twitter). The popularity of the novel in the second half of the 19th century is widely attributed to the industrialization of book production. Thanks to the advent of machine-made paper and stereotype printing (in which text could be reproduced from plates rather than painstakingly typeset by hand), books became affordable goods. But this montage is notable for its emphasis on the parts of the book done by hand—there isn’t a single machine in sight. But Gerwig did her homework. To ensure period accuracy, she enlisted the help of printer David Wolfe and binder Devon Eastland. They not only consulted on the film and sourced period-appropriate equipment, but appear as the printer and binder in the film (with Eastland costumed as a man).

By making Jo fight for her story, her compensation, and her copyright, Gerwig ensures that Jo’s success belongs solely to her.

In a recent encounter with Eastland on Twitter, I asked her about the dearth of machines in the sequence. She explained that though some rudimentary machines for binding tasks had been invented by 1871, machine-trade binding was still in its infancy. Many books were still bound by hand, including Little Women. In fact, Eastland bought a defective copy of the novel’s second edition and disassembled it to learn precisely how it was bound. The only difference between the binding she creates on-screen and the original is the material—the first edition of Little Women was cased in cloth; Jo March’s book is bound in leather. Content to imagine the machine-made paper and the stereoplate process that took place off-screen, I allowed myself to revel in the beauty of the craftsmanship in this scene on my second and third viewings.

It is these considered decisions that make Gerwig’s Little Women much more than just the ninth film adaptation of this popular American novel. It is also a love letter to bibliophiles, Louisa May Alcott, her fans, her publisher, her book-and its binder.

Christine Jacobson is assistant curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts at Harvard University’s Houghton Library. She tweets @internetstine.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.