Discovery,” historian Steven Lubar argued in a blog post on how the digital environment is changing historical research, “is perhaps the stage of scholarship that’s seen the largest change.” Historians now have a vast array of searchable primary sources available to them by just turning on their computers. Archives and libraries across the world publish catalogs and primary sources that have transformed how we do research.

At first glance, discovery appears easy. Google has made us think that finding things on the web is a straightforward process. But every user of Google knows the difficulty of filtering; how do I decide if what I’m finding is worthwhile and relevant? What is missing from my search? While an experienced researcher should have the tools and skills to find her way, there are real issues around discovery of sources and new kinds of research practices for finding things in the digital realm.

One problem is related to how the World Wide Web works. The web was conceived as a network of pages—discrete documents that are connected to others through links. The web is set up to exchange these documents, and most search engines are set up to find them. But when researchers look for things on the web, we are looking for information rather than merely documents. Beyond the formatting, there is very little structure to web pages because the web was designed to be readable by people, not machines. And so while search engines are great at finding keywords, the design of the web itself makes it hard for a researcher to search by subject or utilize the thematic categories that are often the key to how humanists think about their research topics.

The solution to this problem is the Semantic Web, a concept pioneered by web inventor Tim Berners-Lee that has become central to a movement led by the World Wide Web Consortium (the main international standards organization for the web). This movement is nothing less than an attempt to reconceive the web’s underlying structures as a “web of data” rather than a network of pages. Just as hyperlinks are used to connect web pages, the Semantic Web has structures that connect disparate data from many different sources and allow searches to extract information from within websites much more systematically.

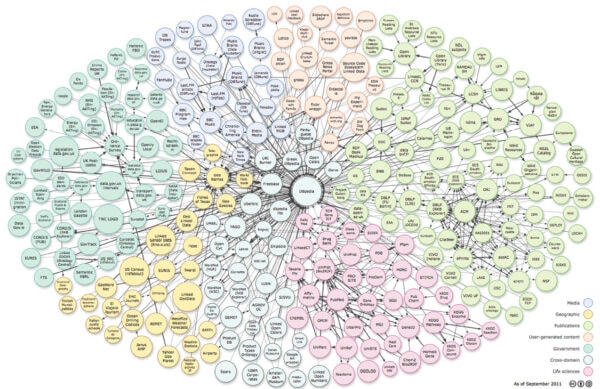

Linked open data cloud diagram as of September 2011 by Anja Jentzsch. CC-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons (for full-size image: bit.ly/1BqiQ5h).

“Linked data” promises to create the web of data by relying on two basic principles: first, that the data is presented according to an agreed model, and second, that it links to a vocabulary that provides an authoritative reference for the data. These vocabularies can be any standard, widely used source for organizing information. These are often familiar classification systems, published, for example, by organizations such as the Library of Congress, the BBC, and the New York Times, and also by newer, web-based organizations, including the Wikimedia Foundation (the organization that runs Wikipedia, among other projects).

One example of this sort of ontology is the Library of Congress Name Authority File (NAF). This resource, according to the library, “provides authoritative data for names of persons, organizations, events, places, and titles. Its purpose is the identification of these entities and, through the use of such controlled vocabulary, to provide uniform access to bibliographic resources.”

If I’m reading a digitized political tract from the 1740s and it mentions the Earl of Orford, then as a reader I know this is a reference to England’s first prime minister, Robert Walpole, but a computer has no way of knowing this, or of knowing whether it refers instead to First Lord of the Admiralty Edward Russell, who died in 1727 and was unrelated to Walpole, or Robert’s son Horace, who didn’t obtain the title until 1791. But if the data that underlies a website containing the name is linked to the appropriate entry in the NAF, search engines become better at finding the historical figure the user is looking for. The other problem alleviated by this sort of structure is that any number of titles, alternate spellings, and pseudonyms can be linked to a single individual. The entry for Horace Walpole in the NAF demonstrates this problem, listing honorifics and pseudonyms: 4th Earl of Orford, William Marshall, Onuphrio Muralto, Horatio Walpole, and many others. For other historical figures, especially those known by a nom de guerre or nom de plume, the problem is even more acute. For example, the NAF lists over 40 variants for “Lenin.”

For less prominent historical figures, the existence of authority files can be even more valuable. Assigning an authoritative name to an individual who was tried at the Old Bailey, mentioned in a newspaper published in 18th-century London, and ultimately transported to Australia on the “First Fleet” allows us to trace the individual through his encounter with the British penal system and to link all the digitized records of these events, enhancing the researcher’s ability to discover new connections.

This kind of linkage also helps alleviate some of the limitations of keyword searching. While it’s easy to find lots of information on the web about the life and career of Sir John Soane, it’s much more difficult to find all the architects who were active in London during the late 18th century. The structure of the web does not support subject searching, but a growing number of projects—Wikidata, Geonames, Freebase, BBC Music, and many others—are changing this. In August, the Getty Research Institute announced that it has released the Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Names as linked data. This resource of over 2 million names lists “current and historical places, including cities, archaeological sites, nations, and physical features.” There is even a nascent NEH-funded project called PeriodO that aims to create linked data for historical periods.

This web of data is growing rapidly. The potential for transforming the kinds of historical research that can be done using web-based sources is huge. As information is increasingly published on the web using linked data standards, the possibilities of discovering connections between disparate sources grow, giving historians better tools for interpretation of the past.

is the AHA’s director of scholarly communication and digital initiatives.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.