Given our inheritance of a “mutilated world,” as poet Adam Zagajewski so evocatively invoked, the idea of nonviolence and its practical uses continue to fascinate, intrigue, influence, inspire, and encourage across age, race, and political demographics. As an educator, a historian, a person of South Asian origin, and an immigrant in the United States, I have always been deeply interested in the study of nonviolence as an intellectual, political, and historical idea. The driving force behind my pedagogy is to teach and learn about nonviolence in the context of a world in crisis and how to navigate this world and meet it with compassion and care. That there might be a gentler and more ethical approach to our lives and to our world, and that it might be achieved through nonviolent action, seems to be a vital question that needs to be urgently and comprehensively debated and answered.

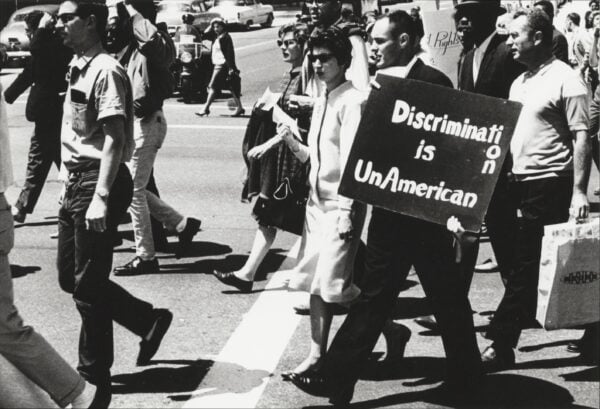

In the 1960s, CORE activists marched in Madison, Wisconsin, in support of racial equality. Gerald Marwell/University of Wisconsin–Madison Archives Collections

Since coming to the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 2019, I have therefore focused my pedagogy on how to effectively teach the histories of diverse nonviolent ideologies in the American classroom. Both educators and students engage with these issues in and outside the classroom, and they have questions that need to be answered from a global historical perspective. It is with this need in mind that I proposed a comprehensive digital repository in 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, for which I received generous support from the Board of Visitors of the UW-Madison Department of History. This became the Nonviolence Project (NVP).

An example of what bell hooks called “engaged pedagogy,” the NVP uses the tools of public history and digital humanities to prioritize student learning and research through internships. For teachers, our engagement with students begins with reflection: Who makes history? What are the perspectives that shape our understanding of our past? Today, history, memory, and mythmaking about nonviolence are in contest with one another worldwide, in the public sphere and in academia. What students lack is an understanding of the contexts of such resistance, the ethical debates surrounding such action, and the political controversies engendered by these ideologies. I teach them that history is fundamentally an act of reckoning with the past, of questioning the structural nature of inequities, and of engaging critically with the contexts of power relations through which knowledge is generated. The NVP was created, in part, to highlight how nonviolence has remained one of the most popular, important, and effective weapons of political resistance for those who are underrepresented, minoritized, and oppressed.

I designed the NVP in keeping with the Wisconsin Idea, that UW-Madison and its students work to benefit every person associated with the state of Wisconsin. Since the civil rights era, UW-Madison has been a significant space for civil disobedience and nonviolent protest. Unfortunately, over the last decade, there have been concerted efforts to erase this history and mission. The NVP therefore consciously revives this memory and carries forward this legacy, training students to be active collaborators in shaping the future of democracy in the United States and the world. Given the university’s diversity, the concerns of the NVP are global as well. I am keenly aware, however, that UW-Madison is a Research 1 university with all the resources that make an experimental pedagogical project like the NVP possible, and my students and I are conscious about navigating our privilege in this regard with all due care.

History, memory, and mythmaking about nonviolence are in contest with one another worldwide.

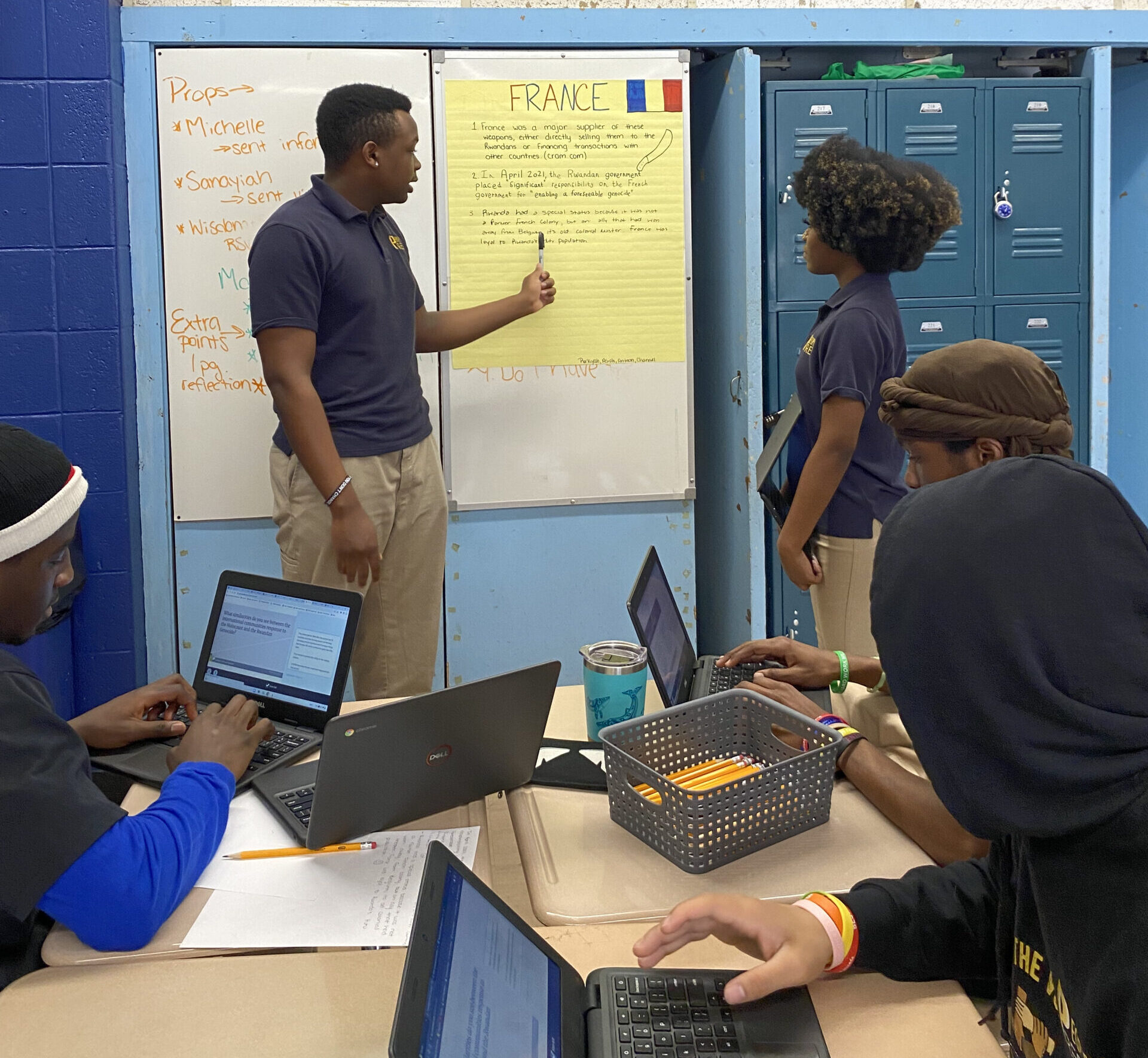

In order to engage a wider audience in keeping with the Wisconsin Idea, students needed a platform to communicate academic research in a public-facing manner. The form that the NVP takes, as a digital repository of research articles, biographies, and social network mapping, helps us to disseminate in an accessible and legible manner information about how the intellectual concept of nonviolence spread from South Asia to the United States to South Africa. Student interns create self-directed scholarly works, discovering the history of nonviolent activism for themselves and then sharing their rigorous academic research with a nonacademic audience via the website. So far, 24 undergraduate students and three graduate students have worked with NVP, and six new undergraduate interns joined us in the fall, producing fantastic scholarship on civil rights activism in diverse areas such as law, public policy, environmentalism, antiwar demonstrations, and gender rights in a global context.

These student interns receive from librarians, archivists, public historians, and oral historians professional training in archival research techniques, public-facing scholarship, and writing. They learn to use UW-Madison’s libraries and their extensive holdings and gain experience working with the university’s treasure trove of oral history interviews. Some work for the groundbreaking Center for Campus History. The essays students produce are academically rigorous but written in jargon-free and accessible prose. Interns also consult regularly with archivists at the Wisconsin Historical Society, producing important research on topics including CORE and women’s activism.

Students learn to form opinions based on rigorous archival work and to combat misinformation. Their research helps them to develop an empathetic relationship with the world, based on collaboration and intercultural understanding. They learn to envision themselves as creators of narratives that can lead to consequential political, social, and legal changes in the world. And from an educational point of view, they actively develop a particular kind of critical understanding of the many ways that history can be made and articulated from archival sources.

They communicate that history across many topics and using many mediums. Students have produced a Spotify playlist of protest songs; a syllabus for learning about nonviolence; an Instagram account that highlights civil resistance movements; and a GIS map of Madison, highlighting the locations of some of the most famous civil disobedience events student researchers have worked on. Others have produced wonderfully detailed research on civil resistance in Hong Kong and written biographies of activists in Latin America, using untranslated records and documents. There has also been a series of articles on the uses of nonviolent civil activism by students on UW-Madison’s campus, including protests of the Vietnam War, LGBTQ+ activism, and the gay purges in 1962. Students have also written about environmentalism, Earth Day, and the activism of Aldo Leopold and Senator Gaylord Nelson. There are now multiple digital projects that K–12 educators might use on our website. Such research, based on local events with global significance, grounds our students’ understanding of nonviolence within their experiences at UW-Madison and within their own world.

As an educator, I hope that this engagement also creates cultural competency, enhances compassion and empathy, and teaches them to be inclusive and socially conscious and ethical in their worldview. And in fact, my colleagues and I have noticed that NVP student interns emerge with better research and writing skills, better critical understanding of complex historical processes globally, and, ultimately, a more empathetic understanding of suffering and resilience.

NVP student interns emerge with a more empathetic understanding of suffering and resilience.

Students bring their own perspectives and interests to the NVP and integrate them in their research. One researcher focused on the development of harm reduction and strategies like hunger strikes in US prisons. Another explored how Indigenous and Afro-Caribbean communities in Latin America have resisted human rights abuses. As a third student intern graduated and headed to law school, he said that this research had been “uniquely inspiring and even life-changing. . . . Nonviolence is not merely a source of pacifism but can be a profoundly strategic and impactful tool.”

Above all, students have conveyed that participating in the NVP changes their perception of nonviolence from an abstract concept to a conscientious practice often performed daily. As one of our student interns said, “This project encourages people who may feel helpless in matters happening worldwide feel as if they have a voice and feel empowered. Understanding that there is power in knowledge, power in empathy and understanding, as well as in solidarity.” Another student commented, “It’s heartening to see how many people care about nonviolence . . . it gives them hope for the future and what the future can be!”

The NVP is a pedagogical model that can be adapted at other institutions that want to combine history education with practical training for students in research, writing, and digital content creation. Such training enables students to demonstrate that their liberal arts education is adaptable to a wide range of practical uses. Our project, by practicing connective and collaborative research, trains students to develop civic responsibility toward the communities they inhabit. We welcome other institutions to use our modules for resources and syllabi, and we would be happy to help others develop similar programs.

When I teach my students about the civil rights movement, we often discuss Martin Luther King Jr.’s poignant piece “Unfulfilled Dreams.” There is enduring tragedy and discord in our world, and yet there is also an element of indomitable faith and hope that we can contribute to building a better future. Whether we live to see that future realized or not is perhaps immaterial, but the will to do so is profoundly necessary. King said, “We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope.” Infinite hope and empathy are radical political actions, and the most important components of nonviolent action. Cultivating these attributes in the face of setbacks requires patience and perseverance, and an understanding of the political genealogies of global civil rights activism. The NVP trains students to understand, research, practice, and disseminate this history in the world beyond the university for the hopes of a more just society.

Mou Banerjee is assistant professor at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and director of the Nonviolence Project.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.