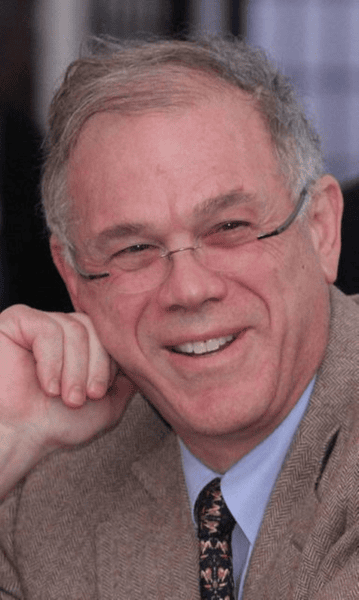

Jonathan K. Ocko

Jonathan K. Ocko, professor of modern Chinese history and head of the department of history at North Carolina State University, died suddenly and unexpectedly at age 68 on January 22, 2015, in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Born in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, Ocko grew up in New York and in the San Francisco Bay Area. He returned east for college and graduate school, receiving his BA in history from Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, and his MA and PhD from Yale, where he studied under the renowned historians of China Mary Wright and Jonathan Spence. Ocko began his professional career at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, and then Wellesley College, before coming to North Carolina State University in 1977. He was made full professor in 1992 and had been department head since August 2002. At North Carolina State, Ocko was involved in a variety of campus-wide initiatives, serving on the Administrative Process Review Committee and the Digital Assets Management Task Force. Ocko was instrumental in securing the grant that started Chinese language instruction at NC State University, and he negotiated several institutional affiliations with China. In 1983, Ocko began his affiliation with Duke Law School, where he was an adjunct professor of legal history. At Duke, Ocko taught courses in Chinese legal history and Chinese law and society. A co-convener of the Triangle Legal History Seminar, he had an insatiable interest in both his own specialty and legal history in general. An outstanding scholar, Ocko received a National Humanities Center Fellowship, a Fulbright-Hays Faculty Research Abroad Grant, a Chang Ching-Kuo Foundation Grant, a Rockefeller Foundation Fellowship in the Humanities, and a Henry Luce Foundation Grant. Along with numerous articles on Chinese law and society, Ocko’s written work included Bureaucratic Reform in Provincial China (1983) and an edited volume (with others) entitled Contract and Property in Early Modern China (2004). At the time of his death, he was completing a study on concepts of justice in late-imperial China and was actively conducting research for a second project on legal consciousness in late-imperial and contemporary China. Fluent in Mandarin, he traveled to China frequently and developed close relationships and friendships with many Chinese academics and scholars. He was a founder and director of both the International Society for Chinese Law and History, and the Duke Law-Shanghai Jiao Tong University KoGuan School of Law Financial Law Forum. Along with bringing so many people together, Ocko was a selfless mentor to innumerable young scholars of Chinese legal history on both sides of the Pacific.

Ocko loved North Carolina State University and sought both to promote and guide the university wherever possible. He was a passionate advocate for the importance of history and the humanities more generally within a land-grant university. His great mission was to grow the history department; he succeeded in increasing the number of faculty within the department and oversaw the expansion of the graduate program to include a PhD in public history. Ocko was an advocate for his colleagues, taking special interest in junior faculty, adjuncts, and graduate students. He helped many young scholars within the department further their careers, and his enthusiasm for history and the humanities in general brought him many adoring students and innumerable thankful colleagues.

Having rowed for the varsity team at Trinity College, Ocko continued to enjoy playing sports throughout his life, although most of his recent athletic endeavors were with his four grandchildren. Like many readers of this magazine, he rooted for his university’s teams with a passion, knowing the students and the hours of hard work they had put into their training. He savored every Wolfpack victory in every sport, especially when they came against neighboring North Carolina or Duke University, but had no desire for North Carolina State to win at all costs.

To his colleagues in the history department and throughout the university, Jonathan was a leader, a thinker, and a friend. And like any close friend, he brought joy to those who knew him. He was famous for poking his head into colleagues’ offices, ostensibly for a business-related issue, but then staying to chat about sports, politics, or a bottle of wine that had brought him and his wife, Aggie, transcendent pleasure. Likewise, any trip to his office (his door was almost always open when he was in) could be a fabulous adventure in time management. How many times have I and others walked into his office with a quick question, the answer to which became the prelude to a story about rowing on the icy Connecticut River, the perils of Yale grad school in the 1960s and ’70s, his grandson’s jump shot, a hilarious cultural misunderstanding on his last trip to China, his triumphs and failures in the classroom, or the successes of a colleague or former student? Almost invariably, these stories were interrupted by a telephone call (his phone rang incessantly), but any attempt to excuse oneself at this point was rejected with an enthusiastic insistence, a beaming smile, and a wagging index finger held aloft to indicate that the interruption would be only one minute. There was nothing heavy-handed about this method; indeed, I almost always chose to stay. The stories were too funny, the political analysis too insightful, and the laugh so infectious that, waiting aside, it was clearly the best possible use of my time. He wanted to make the world a better place, and on the personal, family, institutional, and societal levels he succeeded in doing so. He will be missed.

Ocko is survived by his beloved wife, Aggie; his sons, Peter and Matthew; their wives; and four adoring grandchildren.

Charles C. Ludington

North Carolina State University

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.