The 21st century is deficient in many things, not least of all the opportunity to join together joyously and genuinely in song, free of guile and cynicism.

Faculty members from across the University of Pittsburgh joined together to form a United Steelworkers local. Courtesy United Steelworkers

My initial experience with such a collaborative chorus came during my first semester at the University of Pittsburgh in the fall of 2019. I sat in a circle with my colleagues from across job classes, departments, and schools. We shared perspectives, listened to one another’s problems, and considered how we could collectively address our issues. At the end of our discussion, we sang, a cappella, “Solidarity Forever,” Ralph Chaplin’s 1915 labor anthem. And as I sang, somewhat abashedly, I looked around at these new friends I was making, and my voice grew louder. I felt growing confidence in my heart that “we can break their haughty power” and gain our freedom now that we’d learned that the “union makes us strong.”

Being an academic historian has been in many ways an isolating existence for me. Many of my professional tasks are solitary. I read books. I prepare lectures and PowerPoint presentations. I request archival documents. Even when collaborating on research and writing, I perform much of the actual work in the company of only myself. The constant dislocations of the academic job market—moving among postdoctoral fellowships, one-year positions, and other temporary work—leave little time for socializing and building lasting friendships. Teaching responsibilities and publishing requirements allow scant free time to forge connections in other departments or build broad campus communities. In other ways, academics are in constant competition for a diminishing number of jobs, for fellowships, for space in publications, and for research money. We are constantly reminded of and divided by our status, which allocates both resources and respect. Universities attempt to remedy inequalities linguistically rather than structurally, as though renaming “non-tenure track” as “appointment stream” or “clinical” faculty will address the material basis of the hierarchy.

We are the union, we told our colleagues.

But I will not expand here on grievances with the system—those have been well established. There is no shortage of criticism of the ways in which the university is increasingly a moneymaking machine rather than a center of teaching and intellectual inquiry working for the public good. I have spent hours hearing, reading, and speaking about these concerns, bewailing the fate of our profession. This is not to say that critiques are not valid or worthwhile—they are. We must identify the problem before we can solve it, and criticism is a necessary first step. The problem lies in doing nothing tangible to move beyond criticism.

Working collectively to establish a union showed me concrete ways to move forward. The effort began in 2015, when a group of Pitt faculty decided to work with the United Steelworkers, an international union based out of Pittsburgh with several academic locals, on a unionization campaign. Our faculty joined a wave of unionization efforts among faculty and graduate students in the past 10 years at universities across the country. Despite laws in many states that limit the power of public employees to unionize, faculty have worked with a variety of international unions to form locals. Though faculty unions date back to the early 20th century, their numbers are increasing and their functions are changing as faculty face the corporatization of the university system and widespread funding cuts. This trend suggests that higher education is a key sector for new labor organizing. Through unions, faculty want the power of collective bargaining to improve their working conditions and students’ learning conditions. Through collective bargaining and a legally enforceable contract, they can address both local issues, such as pay, and the broader concerns of many in higher education, such as academic freedom and precarious employment contracts.

I became involved with the Union of Pitt Faculty Organizing Committee when, on my first day of teaching, a labor organizer and a gender studies professor visited my office and asked whether I would be interested in learning more about the efforts to form a union. They explained that the union, which included faculty of all job classes, had already collected authorization cards. By the time I arrived in 2019, they were just waiting on a faculty-wide vote on whether to unionize. As they waited for the Pennsylvania Labor Relations Board to set a date for the vote, organizers continued to reach out to colleagues and hear their points of view.

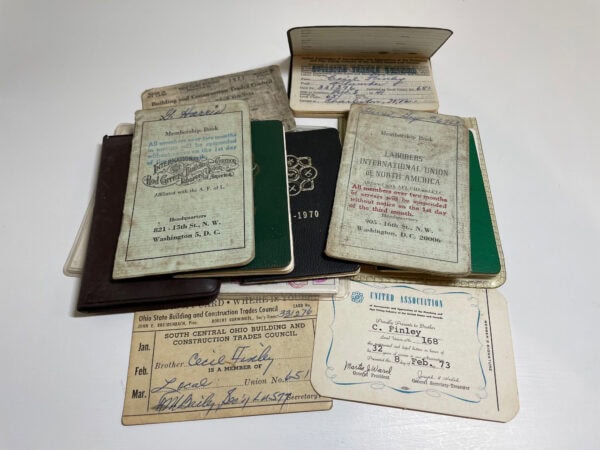

In joining the Pitt Faculty Union, Alexandra J. Finley becomes a fourth-generation union member.

Before I knew it, I had signed up to go and speak with my new coworkers about the union campaign. Despite being a naturally reticent person, my long family history of union membership pushed me into action. I found myself knocking on office doors, flagging folks down after their classes, and calling coworkers on the phone. I learned my way around campus through this process. I had to find Benedum Hall so I could visit a class there. I learned that I share a building with the political science department after speaking to faculty in their offices. I met chemists, linguists, astronomers, engineers, and psychologists. I listened to the experiences of longtime adjuncts, distinguished professors, and first-time lecturers. These new ties helped break through the typical isolation of academic work.

By and large, what I found through these discussions was commonality. Most faculty worried about job security, lack of administrative transparency, the need for greater shared governance, academic freedom, growing workloads, and funding. These worries played out differently in different job classes and departments. Adjuncts had to prepare syllabi on the day the semester began, as they had not been informed of their teaching responsibilities until that very morning. Assistant professors worried about increasing research requirements for tenure. Tenured faculty had witnessed a decline in shared governance. Part-time faculty hated to tell inquiring students that they didn’t know when or whether they would be teaching next semester. When the COVID-19 pandemic started in the winter of 2020, three new concerns came to the fore: health and safety, family and dependent care, and intellectual property rights for online teaching material. Some faculty felt completely out of touch with the university; they hadn’t spoken to a colleague in months, even before the pandemic limited campus visits.

Rather than our fretting aimlessly, unionization gave us a route to having our needs addressed. We are the union, we told our colleagues. The union isn’t an outside party or an administrator; the union is us. When we have a union, our voices have to be heard; the administration has to offer us a seat at the bargaining table. When negotiating a union contract, we can introduce legally enforceable language that addresses job security, academic freedom, intellectual property rights, equity, pay, and family leave, among other key issues.

Unionization takes the genuine despair and anger behind our grievances and turns them into something positive.

Overall, the faculty at Pitt saw the positive change that could come from forming a union. We realized that, regardless of job class or department, we had a great deal in common—we all labor in the same ecosystem. In October 2021, 71 percent of faculty voted in favor of a union. The outside support we received from the greater Pittsburgh community, local politicians, and the Pitt student body made the decision that much clearer. At the time of writing, the Pitt faculty are in the process of electing a Committee of Representatives and a Bargaining Committee. These individuals will represent faculty proportionally, according to school, division, and job class. They will be assisted by a Communications and Actions Team, which acts as a resource for their colleagues, conveying information back and forth from representatives to faculty throughout the negotiation process. The Bargaining Committee, with the legal support of United Steelworkers, will meet with administration representatives and begin to bargain a contract in the spring term of 2022. It is a democratic process throughout; the resulting contract must be approved by faculty vote. The University of Pittsburgh faculty were the largest new faculty union to form in 2021, so the negotiations will take longer than on a smaller campus, but we look forward to bargaining a contract that will best serve all of those represented.

I would like to suggest that inclusive faculty unions are academic historians’ best hope for remedying the many ills we see in our professional lives. As academics, we excel at identifying problems, pushing back on ideas, and critiquing everything around us, but we often stumble when asked to find workable solutions or to apply those same analyses of power to ourselves. Unionization is a way to take the genuine despair and anger behind our grievances and turn them into something positive. It is not a magic fix but a powerful way for faculty to fight for the changes we want to see.

We write alone, we read alone, and we research alone. But we don’t have to fight alone. It’s time to fight not just for our own interests but for those of all our colleagues and, in turn, our students, nonfaculty employees, and our broader communities. Without faculty, there would be no universities, but we must come together for our influence to be felt. One voice singing alone will not draw as much attention as a chorus of many. Singing “Solidarity Forever” to myself, I feel inspired but not particularly powerful. Surrounded by colleagues, our voices blending in a resounding chorus, I feel like change is possible. As part of a union, I feel the alienation and the cynicism fade away, and as naive as it may sound, I truly believe that “we can bring to birth a new world from the ashes of the old.”

Alexandra J. Finley is an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

Related Articles

Sorry, we couldn't find any articles.