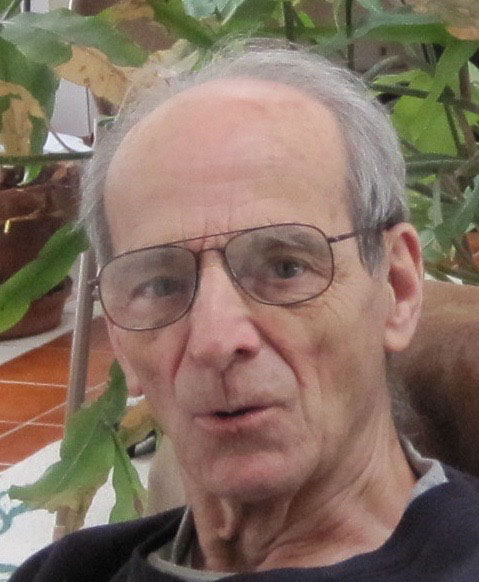

Jan Vansina

Jan Vansina, one of the world’s foremost historians of Africa, died peacefully in Madison, Wisconsin, on February 8, 2017. He was surrounded by his wife, Claudine, and his son, Bruno.

A pioneering figure in the study of Africa, Vansina is considered one of the founders of the field of African history. His insistence that it was possible to study Africa in the era prior to European contact, and his development of rigorous historical methods for doing so, played a major role in countering the idea that cultures without texts had no history.

Born in 1929 in Antwerp, Belgium, Vansina trained as a medievalist before accepting a position in 1952 as an anthropologist in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, then a Belgian colony. After conducting field research and working at the Institute for Scientific Research in Central Africa (IRSAC) in Rwanda, Vansina returned to Belgium to earn a licence (BA) and a PhD at the Catholic University of Leuven, submitting his thesis, “The Historical Value of Oral Tradition: Application to Kuba History,” in 1957. He also spent a few months at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London, getting to know the work of Nigerian historians Kenneth Dike and Jacob Ajayi. Along with them and British scholars Roland Oliver and John Fage, Vansina participated in three major conferences on African history at SOAS. This collaboration helped forge networks that culminated in the publication of the UNESCO History of Africa (1964–99). In 1960, Vansina accepted an invitation from Philip Curtin to join the history department at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Vansina and Curtin created the first program in African history in the United States and trained the first and second generations of specialists in the field. Vansina quickly became a towering figure, writing over 200 articles and 20 books. He combined an encyclopedic knowledge of linguistics, anthropology, and history with a steadfast commitment to rigorous historical research, and a unique talent to recover intricate historical changes in places where few traces of the past could be retrieved.

Beginning with the publication of La tradition orale (1960, English translation 1965), his work led to the acceptance of oral traditions as valid sources of history. Oral Tradition as History (1985), a complete reworking of La tradition orale, subsequently became his best-known book. He promoted the use of interdisciplinary tools, especially historical linguistics, archaeology, and art history, to recover the African past.

Vansina was the first historian to tackle the challenge of reconstructing the past of societies in the rainforest over several millennia. His magisterial Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa (1990) covered more than 2,000 years of history. Several major books followed, including Living with Africa (1994), When Societies Are Born (2003), Antecedents to Modern Rwanda: The Nyiginya Kingdom (2004), Being Colonized (2010), and Through the Day, Through the Night: A Flemish Belgian Boyhood and World War II (2014).

Vansina twice won the African Studies Association’s Melville Herskovits Prize for the best book in African studies and received the association’s Distinguished Africanist Award. In 2014, he won the AHA’s Award for Scholarly Distinction. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1982, from which he quietly resigned when the group failed to denounce the use of torture during the presidency of George W. Bush, and to the American Philosophical Society in 2000.

Vansina retired in 1994 at the age of 65. Living near campus, he remained a generous presence for African historians, students, friends, and many visiting scholars. Every year, he offered the inaugural seminar at the African Studies Program at UW. In his last few months, he worked on a joint article on Bantu languages for the Journal of African History.

Vansina rarely went to conferences and cared little about the social fineries of academia. His creative energy fueled a primary goal: debating with his peers about the meaning of the past, tirelessly searching for new knowledge and new methods, and transmitting his expertise to the public. He was committed to promoting the writing of African history for African audiences. He hoped the younger generation of Central Africans could read rich, up-to-date, and accessible histories of their region. A sense of pride in their past, he believed, could help them to deal with the challenges of the present.

Editor’s note: A version of this essay appears at https://janvansina.africa.wisc.edu/about-jan/. Used with permission of the author.

Florence Bernault

University of Wisconsin–Madison (emerita)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.