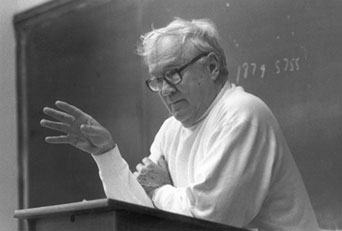

James Patrick Shenton

James Patrick Shenton, a legendary teacher at Columbia University for more than 40 years, died on July 25, 2003, at the age of 78, a few days after undergoing heart surgery. Between 1951, when he began teaching at Columbia, and his retirement in 1996, Shenton’s lecture classes on 19th-century American history, World War II, and the history of immigration and ethnicity in the United States attracted thousands of students. Some, like myself, Sean Wilentz, Thomas Sugrue, and others, were inspired by his teaching to become historians. Many others imbibed a lifelong love of history, and an enduring affection for Shenton. He also regularly taught “Contemporary Civilization,” the central course in Columbia’s “core curriculum.” He supervised graduate students, but his heart lay in undergraduate teaching.

Shenton demonstrated that what makes a great teacher is a genuine passion for his subject and the ability to convey that passion to students. Throughout his Columbia career, he also offered history classes at Montclair College, the Manhattan School of Music, and the Katherine Gibbs secretarial school, not for the money, but because he loved teaching. He was a pioneer in bringing history to television, delivering in the 1960s a lengthy course of lectures on New York’s Channel 13.

Shenton published his doctoral dissertation as Robert John Walker: A Politician from Jackson to Lincoln (1960), as well as a collection of documents on Reconstruction and a number of U.S. history surveys. Teaching, not academic scholarship, was his passion. However, his lectures always reflected the most up-to-date scholarship. He read voraciously, mostly on the daily bus rides to and from Passaic, New Jersey, where he lived with his mother. Long before it became fashionable, his classes offered sympathetic accounts of America’s underdogs and visionaries. His treatment of slavery and Reconstruction was far ahead of its time. For example, in the 1950s, he once invited W. E. B. Du Bois to his Civil War seminar for a discussion of Du Bois’s work, Black Reconstruction in America, then ignored by most historians.

Shenton won every award possible for a Columbia teacher, including the Mark Van Doren Award given out by students (1971), the Great Teacher Award of the Society of Columbia Graduates (1976), and the Presidential Award for Outstanding Teaching (1996). He was also the co-winner of the AHA’s Eugene Asher Distinguished Teaching Award in 1995. His popularity did not derive from lax requirements or easy grading. The length of his reading lists was legendary and he continued to give C pluses and B minuses long after these grades had disappeared from the repertoire of other teachers. He never relied on teaching assistants, grading all the papers and exams himself. He had the amazing ability to remember his students. I recall seeing him encounter a student from a lecture course 20 years earlier and instantly recalling his name.

For many years, Shenton stood out as the conscience of the Columbia faculty. His was a personal radicalism, resting on the primacy of individual conscience and abhorrence of violence rather than membership in any political organization. During the 1930s, he became estranged from the Catholic Church when his parish priest collected funds for Franco’s fascist rebellion in Spain. He refused to bear arms in World War II on pacifist grounds, serving instead in a medical unit. He was part of a group flown ahead of the lines to liberate the Buchenwald concentration camp. What he saw there greatly reinforced his hatred of violence and racism.

During his career, Shenton helped organize Columbia students for a voter registration drive in South Carolina, supported those demonstrating for the university to “divest” from South Africa, and aided clerical workers seeking union recognition from the Columbia administration. In the early 1970s, he flew to Sweden for the weekend to counsel a former student who had gone AWOL from the army for fear of being sent to Vietnam.

During the crisis at Columbia in 1968, he was one of the few faculty members who maintained sympathetic ties with the protesting students, and who was trusted by both white and black demonstrators. With a few other teachers, he positioned himself outside one of the occupied buildings to prevent violence. When the police assaulted demonstrators and bystanders, Shenton was severely injured. The next day, his arm in a sling and his head bandaged, he appeared on NBC Nightly News. In the midst of recounting what he had seen, he stopped and began crying. That moment, broadcast across the country, stripped the last shred of legitimacy from the administration of Columbia president Grayson Kirk.

Shenton was also renowned for leading walking tours of New York City neighborhoods, and for his culinary expertise. He was constantly taking students out to meals at one or another of New York’s ethnic restaurants. Among his publications was an Italian cookbook.

Despite his middle name and being born on St. Patrick’s Day (March 17, 1925), Shenton was of English and Slavic background. He first visited Ireland with his nephew and myself in 1973. He loved the country, but found the food wanting. In the small town of Newport, we chanced upon an inn where several cars with French license plates were parked. “Let’s eat there,” he exclaimed, “the French aren’t having boiled potatoes for dinner.” Sure enough, it was the best meal of our trip.

Shenton was an inspiring teacher, wise mentor, loyal friend, and model of committed scholarship. He probably influenced more Columbia students over the past half century than any other teacher. He will be sorely missed.