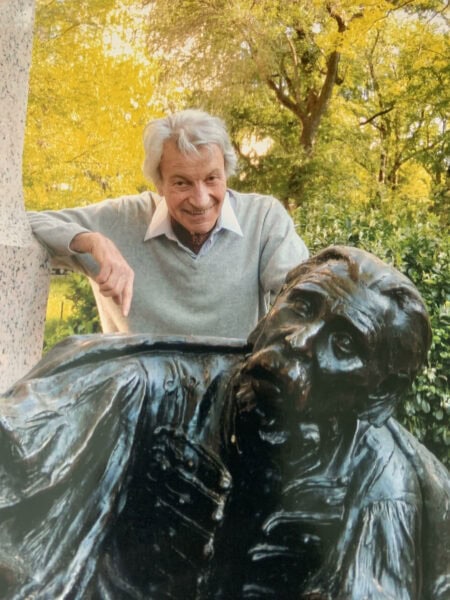

István Deák. Photo courtesy Éva Peck

I thought my name was Stefano!” was one of the most ridiculous sentences István Deák ever threw at me. About 20 years ago, I forwarded him an email, and being the careful reader he was, he immediately noticed I had written “Deák thinks” instead of “István thinks.” He relished that I, his “Italy student,” usually called him by the Italian version of his name, Stefano. The offense he felt at being referred to as Deák was the flip side of that coin: he felt boxed in to being a figure instead of a person. “I thought we were friends! Am I just politics for you?”

Stefano was not just a friend, and I want to use this space to write an obituary that he would want to read. He hated when academic historians wrote only for academics. He declared many times that he learned his craft not from his beloved dissertation advisor at Columbia University, Fritz Stern, but instead from his New York Review of Books editor, Rob Silvers. He thought of history as something that happened in real time. That’s how he taught his graduate classes: Oxford debates that ended with a vote on which historian had been most convincing. (I won three times, lost once.)

Why did so many students at activist Columbia flock to his classes during the 1970s–90s culture wars, even though he taught and wrote almost exclusively about white, mostly male Europe? The answer is simple: Stefano abhorred convenient histories and paid notice to uncomfortable truths. He focused on the human experience and seduced readers to take note through his lively prose. His first book on left-wing Weimar intellectuals was good. Every book thereafter was better, and his last three are masterpieces. I think my favorite is Beyond Nationalism: A Social and Political History of the Habsburg Officer Corps, 1848–1918 (Oxford Univ. Press, 1990), in which he deftly re-created the social, cultural, political, and economic worlds of Habsburg military officers from the Italian Alps to the Carpathian Mountains. I teach his last book, Europe on Trial: The Story of Collaboration, Resistance, and Retribution during World War II (Westview Press, 2015), most. In it, Deák pushed for writing carefully researched history that engaged with the largest of moral questions about personal responsibility, while simultaneously avoiding the pitfalls of heroizing, villainizing, scapegoating, overabstraction, and overindividualization.

The avalanche of memorials in the works are in part a response to his publications. But I think it was his inclusive sociality that built the broad network so eager to commemorate him. István knit together people of every age, gender, denomination, ethnicity, and standing in formal and informal ways: through collaborative projects like The Politics of Retribution in Europe: World War II and Its Aftermath (Princeton Univ. Press, 2000), co-edited with Tony Judt and Jan T. Gross; his visiting professorship with Norman Naimark at Stanford University; deep engagement with the Central European University; and his always packed, always classy cocktail and dinner parties. His wife, Gloria, once quipped that they had probably hosted half of Hungary and a sizable chunk of eastern Europe in their Riverside apartment. His daughter, Éva, remembers the incessant click-clacking of her parents working away at their respective manuscripts, while a rotating door of kind Europeans sifted through, whispering in a Babylonian collection of languages.

The last time we had lunch together in his kitchen, he said, “I wish I had done what Tony [Judt] did. I failed.” I just laughed, and I argued back in the familiar tones he responded to most, “Babe, you made a world where we don’t need to bow to master narratives. You let us have the oxygen to debate, to wonder, to never take any story as more important than another—and yet to not feel useless in our relativism.” He smiled and then offered me some more horseradish.

There are scores of historians in and outside central Europe who attribute their work to Deák. Many of these acolytes virulently disagree with one another. That’s the horizon he opened: history is about the challenge, the care, the empathy, the fight, and writing so people know that it’s explosive matter. You succeeded too, Stefano. And because of you, our vision of the past and present will never be the same. Stefano was a cherished friend who I mourn—but Deák remains a teacher for us all.

Dominique Kirchner Reill

University of Miami

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.