Is the Cold War a distant, indistinct memory, of significance only to specialist historians? Not at all. Interest in the Cold War and its many legacies is alive and flourishing throughout the United States and elsewhere. For example, in New York, State Parks Commissioner Bernadette Castro is responding enthusiastically to veterans’ calls to establish a Long Island Cold War Heritage Trail. In Florida, another group of veterans is lobbying to place surface-to-air Nike nuclear missile sites they once manned in the Everglades on the National Register of Historic Places. In West Virginia, since 1995 more than 200,000 visitors have plopped down $25 each to tour the 153-room concrete bunker where Congress might have reconvened had Soviet ICBMs incinerated the Capitol. The success of atomic tours across the American West too numerous to list here has encouraged a broad coalition of Nevadans to create the Nevada Test Site Historical Foundation. Early next year, their Atomic Testing Museum will open just off the Strip in Las Vegas. Begun as a way to honor his father, Francis Gary Powers Jr., son of the famous U-2 pilot, is drumming up support for a permanent museum site. In Washington, D.C., new legislation in the pipeline is seeking to direct the National Park Service to conduct a study on Cold War sites and is calling for the publication of an interpretative handbook, as well as the establishment of an advisory board to consult on the study.

Is the Cold War a distant, indistinct memory, of significance only to specialist historians? Not at all. Interest in the Cold War and its many legacies is alive and flourishing throughout the United States and elsewhere. For example, in New York, State Parks Commissioner Bernadette Castro is responding enthusiastically to veterans’ calls to establish a Long Island Cold War Heritage Trail. In Florida, another group of veterans is lobbying to place surface-to-air Nike nuclear missile sites they once manned in the Everglades on the National Register of Historic Places. In West Virginia, since 1995 more than 200,000 visitors have plopped down $25 each to tour the 153-room concrete bunker where Congress might have reconvened had Soviet ICBMs incinerated the Capitol. The success of atomic tours across the American West too numerous to list here has encouraged a broad coalition of Nevadans to create the Nevada Test Site Historical Foundation. Early next year, their Atomic Testing Museum will open just off the Strip in Las Vegas. Begun as a way to honor his father, Francis Gary Powers Jr., son of the famous U-2 pilot, is drumming up support for a permanent museum site. In Washington, D.C., new legislation in the pipeline is seeking to direct the National Park Service to conduct a study on Cold War sites and is calling for the publication of an interpretative handbook, as well as the establishment of an advisory board to consult on the study.

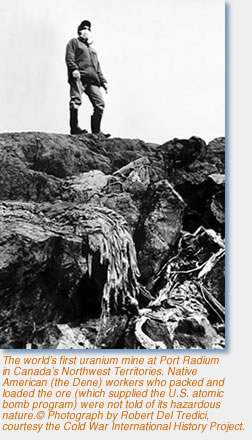

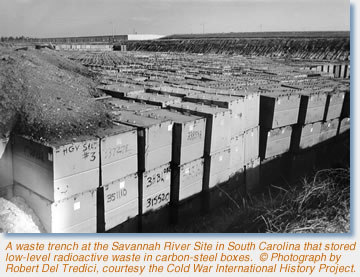

It is in the context of such a widespread and deep interest in the Cold War that 90 museum directors and curators, scholars, historic preservation professionals, veterans' advocates, government officials, media and foundation representatives, and others met in an international conference on September 8–9, 2003, in Washington, D.C., to consider the legacy of the Cold War. The conference participants discussed the most recent historical scholarship; explored how U.S. government agencies are determining the significance of Cold War properties; examined how the Cold War matters to veterans, scholars, and those charged with the preservation of the conflict's documents, artifacts, and places; and assessed museum treatments of the Cold War in the United States and abroad. A special exhibit, Capturing the Bomb: The Nuclear Weapons Photography of Paul Shambroom and Robert Del Tredici, provided a visual backdrop for the conference.

The conference had two objectives: to facilitate interaction among those engaged in interpreting the Cold War and to explore the international dimensions of the struggle. As University of Virginia historian Melvin Leffler pointed out, an outpouring of new archival materials during the past decade has led to new interpretations of the numerous global dimensions of the Cold War, ranging from the Marshall Plan and its impact on the Kremlin to Soviet embroilment in Afghanistan, and from new understandings of the Korean War and the Cuban Missile Crisis to the Cuban role in Africa.

Despite these global ramifications and the worldwide efforts to remember the Cold War (see box on this page for a sampling of these), the conference focused—for practical reasons—mostly on interpretations and expressions of Cold War consciousness in the United States, especially the complexities of balancing numerous factors involved in preserving the physical legacies of the Cold War.

One striking example of such complexity was provided in the report presented by David Berwick, Army affairs coordinator for the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, on the question of preserving the army’s stock of Cold War housing. About 19,000 Capehart and Wherry family units constructed between 1949 and 1962 to house new career soldiers were, according to a 2002 review by the council, designated for renovation or to be sold as the Army deems necessary. Aside from the considerable expense in conducting a preservation review of each building, Berwick claimed that the housing failed to qualify for protection because the expansion of the military’s housing stock would have occurred whether there had been a Cold War or not.

Social and cultural historians will want to know more about the crabgrass frontier of Capehart and Wherry housing that the Advisory Council has decided need not be preserved. For Berwick and many others, the overriding concern is that in establishing priorities among resources, the current mission takes precedence. Navy Cultural Resource Officer Jay Thomas indicated that site managers rarely have the luxury or the inclination to go beyond the requirements of legal compliance, focusing their attention on properties built 50 years ago, or, more important, current needs of the facilities. Sites such as the Washington Navy Yard have multiple historical contexts, forcing managers to balance the interests—and interest groups—of different historical eras. Much of what the Navy has done historically—such as building ships and housing sailors—is now outsourced. Larger ships require bigger, more elaborate piers, making preservation less practical. Base closures, new fleet distributions, and the problems of public access after September 11 add to the woes of the site manager. Finally, striking a chord resonant with Berwick’s analysis, he asserted that knowing what’s special about historic properties, even assuming one had full access to available documentation, is no easy matter, as the Navy’s historical relevance lies at the bottom of the sea.

Social and cultural historians will want to know more about the crabgrass frontier of Capehart and Wherry housing that the Advisory Council has decided need not be preserved. For Berwick and many others, the overriding concern is that in establishing priorities among resources, the current mission takes precedence. Navy Cultural Resource Officer Jay Thomas indicated that site managers rarely have the luxury or the inclination to go beyond the requirements of legal compliance, focusing their attention on properties built 50 years ago, or, more important, current needs of the facilities. Sites such as the Washington Navy Yard have multiple historical contexts, forcing managers to balance the interests—and interest groups—of different historical eras. Much of what the Navy has done historically—such as building ships and housing sailors—is now outsourced. Larger ships require bigger, more elaborate piers, making preservation less practical. Base closures, new fleet distributions, and the problems of public access after September 11 add to the woes of the site manager. Finally, striking a chord resonant with Berwick’s analysis, he asserted that knowing what’s special about historic properties, even assuming one had full access to available documentation, is no easy matter, as the Navy’s historical relevance lies at the bottom of the sea.

Although the Cold War has barely ended for historians, the tug-of-war between mission, preservation, and interpretation is anything but new. While the controversies surrounding the 1995 Enola Gay exhibit at the Smithsonian Institution's National Air and Space Museum have become legendary, few are aware that as early as 1991 Congress directed the Department of Defense to establish a Legacy Resource Management Program to "inventory, protect, and conserve the physical and literary property and relics of the Department of Defense" associated with the Cold War. This "Legacy Project," according to Rebecca Welch, a historian in the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the project's second task manager, was one that the department did not ask for or want. Initially her project staff visited installations in the continental United States and Alaska, Asia, and Europe, consulted with counterparts within the government and historical experts, examined existing federal and state laws and regulations, and began drafting the mandated report to Congress. Welch's objective—to take guidelines developed by Paul Green, preservation officer at the Air Force Combat Command, and extend them to all installations of the Department of Defense—remained unfulfilled, though she deserves much credit for encouraging the Army and Navy to move toward servicewide guidelines on Cold War properties. Beyond the report submitted to Congress, Welch and her team of contractors authored a series of multi-service studies, as well as a database of Cold War material culture assets. Uniting civilian preservationists and military operators, the services, as well as headquarters and the field, and finally scholars in a common effort to define the significance of Cold War places and things was difficult for Welch and will no doubt challenge others as well. Any serious American effort to record the manifestations of the Cold War should draw inspiration from the superb fieldwork conducted by English Heritage and published in 2003 under the title, Cold War: Building for Nuclear Confrontation, 1946–1989.

Notwithstanding the differences of opinion and approach the meeting brought to the fore, one of the most striking aspects of our discussions was the uniform recognition of the evocative power of Cold War places and artifacts. In thinking about the Cold War, one site to which the mind almost invariably races is Berlin. While George Washington University historian Hope Harrison demonstrated how the building of the Berlin Wall was more a product of East German leaders' desire to shape their own destiny than a calculated move on the part of the Soviet leadership in a larger struggle against the West, archaeologist Axel Klausmeier of the Technical University at Cottbus showed us what is now being done, nearly a decade and a half after its fall to identify and possibly conserve the wall as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, featuring Europe's quintessential Cold War relic.

While all participants acknowledged that the Cold War was much more than merely a military struggle restricted to any nation's borders, no one explicitly addressed the thoughtful questions raised by Craig Manson, assistant secretary of the interior: How much preservation is too much, and what should the balance be? Dan Holt, director of the Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum, pointed out, for instance, that as the civil rights movement is embedded in the story of international ideological competition, his museum's new exhibit on the Eisenhower presidency considers Little Rock alongside containment. University of North Carolina historian Roger Lotchin argued that California cities, companies, and congressional representatives have to be put in the display cases as well, because broad municipal coalitions there coalesced around successful drives to secure Cold War manufacturing and research assets.

But preserving land- and cityscapes is often unrealistic, and the wind may, in fact, be blowing in the opposite direction. Other types of documentation, such as oral history testimonies, video documentation, or museum exhibits that feature these and other media may substitute for lost sites and structures, though exactly how these sources might convey the atmospherics of the Cold War remains unclear. One view is that whatever is kept, and certainly whatever is exhibited, should connect personal stories and places to global developments. A forerunner in this regard is the Norwegian Aviation Museum, located in Bodø, a town some 100 miles north of the Arctic Circle, where, we learned from curator Karl Kleve, museum professionals and historians are seeking to explain community change and international politics through large, complicated objects like radars and airplanes. Cold War scholars, too, are increasingly working at the intersection of localities and transnational developments: a conference (“Lives and Consequences: The Local Impact of the Cold War”) organized in April 2003 by historian Jeffrey Engel showed that the interdynamics of high politics and localities is now becoming a focus of scholarly research. Describing these interconnections in popular and academic histories will, as Kleve indicated, require practitioners to make intelligible to the public the arcane languages of science, arms, and preservation; to address the power of stereotypes; to draw together civilian participants and military veterans; and, last but not least, to come to terms with the subjects of Cold War secrecy and document declassification.

But preserving land- and cityscapes is often unrealistic, and the wind may, in fact, be blowing in the opposite direction. Other types of documentation, such as oral history testimonies, video documentation, or museum exhibits that feature these and other media may substitute for lost sites and structures, though exactly how these sources might convey the atmospherics of the Cold War remains unclear. One view is that whatever is kept, and certainly whatever is exhibited, should connect personal stories and places to global developments. A forerunner in this regard is the Norwegian Aviation Museum, located in Bodø, a town some 100 miles north of the Arctic Circle, where, we learned from curator Karl Kleve, museum professionals and historians are seeking to explain community change and international politics through large, complicated objects like radars and airplanes. Cold War scholars, too, are increasingly working at the intersection of localities and transnational developments: a conference (“Lives and Consequences: The Local Impact of the Cold War”) organized in April 2003 by historian Jeffrey Engel showed that the interdynamics of high politics and localities is now becoming a focus of scholarly research. Describing these interconnections in popular and academic histories will, as Kleve indicated, require practitioners to make intelligible to the public the arcane languages of science, arms, and preservation; to address the power of stereotypes; to draw together civilian participants and military veterans; and, last but not least, to come to terms with the subjects of Cold War secrecy and document declassification.

Few places in the United States are more secret than the Cold War "signature facilities"—the phrase comes from the agency's chief historian and preservation officer—of the Department of Energy, and arguably few places deserve more the status of Cold War emblems. These physical sites range from the monumentally stunning to mere holes in the ground (such as the Sedan Crater, the product of an experiment to develop engineering uses for nuclear explosives) and the curiously strange, such as the Pantex Plant near Amarillo, Texas, where for over a quarter century all U.S. nuclear weapons have been assembled and disassembled. Although unlikely to become a Cold War museum, Pantex's relevance to any scientific, economic, and cultural understanding of the Cold War is indisputable.

Preservation of the Cold War's physical legacy is thus caught up in an arena of contention where public memory, emotions, agendas, and scholarly arguments collide with concerns over representation, community economic development, life-and-death environmental issues, as well as a host of governmental regulations from design codes to property rights to preservation requirements. Much like the Cold War, these battles are waged simultaneously on different continents, all too often with the chief protagonists unaware of experiences in other places. Respected for our knowledge of the past, in the business of Cold War memory, historians will ultimately be judged by their ability to engage thoughtfully with unfamiliar professional questions. We hope the conference has contributed to this process.

—Keith R. Allen is a senior historian at History Associates Incorporated. Christian Ostermann is director of the Cold War International History Project at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.