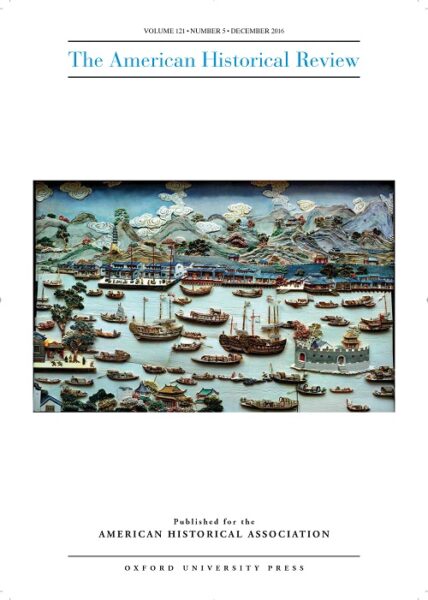

Located in Guangdong province, Canton (Guangzhou) was for many years the only port in China that was open to foreign traders. It was also the site of the events that led to the first Opium War. The city and its tiny but highly cosmopolitan foreign enclave provide one of the primary settings for Amitav Ghosh’s historical novels Sea of Poppies, River of Smoke, and Flood of Fire. Collectively known as the Ibis Trilogy, the books and their author are the subject of this issue’s AHR Roundtable, titled “History Meets Fiction in the Indian Ocean: On Amitav Ghosh’s Ibis Trilogy.” View of Canton, late eighteenth century. Ivory, paint, and gilt. Peabody Essex Museum, AE82856. Photo by M. Sexton, 2006. From “Rise & Fall of the Canton Trade System,” MIT Visualizing Cultures.

Transnational approaches to history have long been a hallmark of the American Historical Review, and this is especially prominent in the December issue. It features an AHR Forum on the metropolitan histories of empire; an AHR Roundtable on Amitav Ghosh’s Ibis Trilogy (including an essay by the novelist himself); and an AHR Conversation in which seven prominent historians share their assessments of the 20th century. “In Back Issues” calls attention to our extensive inventory of articles, going back 121 years. The issue also contains nine featured reviews along with our regular book review section. We continue to alert readers to potential digital resources for research and teaching in the “Digital Primary Sources” section.

Cultures of Colonialism in the Metropole

The AHR Forum, “Cultures of Colonialism in the Metropole,” brings together three articles on colonial elements or experiences in the European metropole. As Marc Matera notes in his introduction, “Metropolitan Cultures of Empire and the Long Moment of Decolonization,” empire abroad shaped the development of metropolitan imperial cultures and identities, and these essays reflect the growing interest among historians in the final decades of colonial rule. Matera’s introductory essay situates the three articles within broader historiographical trends and highlights lessons they offer to historians on the metropolitan reverberations and afterlives of imperialism.

In the first article in the forum, “The Capital of the Men without a Country: Migrants and Anticolonialism in Interwar Paris,” Michael Goebel combines urban and global history by situating the early intellectual history of liberation movements in the everyday lives of migrants in the metropole. Goebel pays particular attention to immigrants from across the French Empire who became leaders in their ethnic communities in Paris. Their politicization owed much to the fact that the global disparities of the imperial order were becoming increasingly visible from a Parisian vantage point. Cross-community exchanges further highlighted these disparities and fueled the spread of anticolonial ideas. Anti-imperialist activists from beyond the empire thus helped transform Paris into a productive center of anticolonialism.

From Paris we go to London, specifically the London Zoo. In “Murder at London Zoo: Late Colonial Sympathy in Interwar Britain,” Jonathan Saha takes up the tragic case of San Dwe, a young Karen man from Burma who was employed as one of the zoo’s elephant-drivers. In 1928, his roommate Said Ali, a famous mahout, was murdered in his bed, bludgeoned with a sledgehammer. Dwe claimed that a group of white men had attacked Ali. The police, however, swiftly dismissed his explanation of events. Even though Dwe was the prime suspect in this brutal crime, his case garnered public sympathy, particularly from loyalist Karen nationalists, London Baptists, and retired colonial officials. While all three groups campaigned for his release, the petitions and letters they sent to the Home Office on his behalf deployed normative imperial understandings of race, gender, and sexuality. Saha’s article historicizes the sympathy expressed by Dwe’s varied supporters to demonstrate how emotion, imperialism, and justice were entangled in interwar Britain.

The Smithsonian Institution on the Mall in Washington, DC, provides the setting for the next article. In “Decolonizing the Smithsonian: Museums as Microcosms of Political Encounter,” Claire Wintle explores the curation of the Asian and African collections at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History between 1950 and 1970. Wintle performs a close analysis of museum archives to reveal the diversity, dynamism, and occasionally progressive nature of museum anthropology during a period that is often considered uninteresting or even moribund. Wintle finds entanglements between museums and US government policy, as well as evidence that cultural representations in US museums were influenced by the specificities of colonization and independence in different regions of the Global South.

Thinking about Historical Fiction

Commissioned by the AHR editor in April 2015, “History Meets Fiction in the Indian Ocean: On Amitav Ghosh’s Ibis Trilogy” gathers four historians to reflect on Amitav Ghosh’s series of historical novels commonly known as the Ibis Trilogy.Sea of Poppies (2008), River of Smoke (2011), and Flood of Fire (2015) are set in India and China around the time of the first Opium War (1839–42). The roundtable concludes with a response by Ghosh.

In the first essay, “Empire and Exile: Reflections on the Ibis Trilogy,” Clare Anderson explores the relationship between “history” and “fiction” in Ghosh’s trilogy. For Anderson, the novels constitute a means of exploring the relationship between the local and the global in the making of the modern world. She describes how Ghosh uses opium as a narrative device to articulate the many degrading effects of imperialism and connects them to the history of forced labor mobility. Despite a shared political project that seeks to give dignity to subaltern people in history, Anderson argues, the novels’ literary representation of the lives of men, women, and children is in some ways more nuanced than historians’ empirical constructions, which are necessarily pieced together from fragmented colonial archives. Thus, she writes, the line between Indian Ocean “history” and “fiction” becomes unquestionably blurred.

In “The Novelist as Linkister,” Gaurav Desai contextualizes the three novels as part of a growing scholarly interest in oceanic narratives of the colonial encounter. He suggests that Ghosh’s earlier writings on transoceanic and transnational connections provide a useful frame for reading the trilogy, and highlights the materiality of the ocean and nonhuman agency as important features of the narrative. His article concludes with a consideration of how postcolonial scholarship, developed in the context of British colonialism and its aftermath in South Asia and Africa, might usefully engage with the work of sinologists and vice versa.

In “Amitav Ghosh and the Art of Thick Description: History in the Ibis Trilogy,” Mark R. Frost considers the three novels as works of microhistory in which the author’s devotion to thick description produces numerous fresh understandings. He highlights Ghosh’s recreations of historical spaces and historical languages, both of which provide invaluable insights for readers. This essay also addresses Ghosh’s credentials as a historian. Frost suggests that one weakness of Ghosh’s first installment in the trilogy, Sea of Poppies, was his failure to read Victorian primary sources with a sufficiently critical eye. He concludes, however, that overall Ghosh remains a historiographical torchbearer who for much of his career has been well ahead of the academic curve in exploring the past connections and convergences of the Indian Ocean world.

In the last comment, “Views from Other Boats: On Amitav Ghosh’s Indian Ocean ‘Worlds,’” Pedro Machado suggests that bringing fiction and history into relation with one another can produce a mutually beneficial dialogue about the nature of sources, archives, and the methodologies we use in producing accounts of the past. This is especially true for stories involving individuals at the “margins” of history, whose voices are difficult to recover. But Machado challenges the trilogy’s vision of the ocean as a British lake whose dynamics were defined by the logics of empire and driven by the force of capital. Rather, he underscores the continued significance of South Asian vernacular mercantile networks in maintaining commercial interests.

In “Storytelling and the Spectrum of the Past,” Amitav Ghosh responds to these four essays. He argues that historical fiction is one of several modes of discourse about the past, and that while academic history is certainly the most authoritative of these discursive fields, it also shares certain commonalities with historical fiction. There are, for example, some areas of overlap between historical fiction and such branches of academic history as microhistory and military history, especially in their envisaging of time. There are areas of overlap with histories of affect and emotion as well. Ghosh also touches on the expansion of India-China studies in recent years, and the rich possibilities that have been opened up because of this development.

History after the End of History

This year’s AHR Conversation takes up the theme “History after the End of History: Reconceptualizing the 20th Century.” The interchange was moderated by Alex Lichtenstein, interim editor in 2015–16, and the discussants are Manu Goswami, a historian of South Asia; Gabrielle Hecht, a specialist in the history of technology and African history; Adeeb Khalid, a scholar of modern Central Asian history; Anna Krylova, a historian of modern Russia who is also interested in questions of the theory and methodology of historical writing; Elizabeth Thompson, a historian of the Middle East; Jonathan Zatlin, a scholar of modern Germany; and Andrew Zimmerman, a scholar of 19th-century transnational and comparative history with a strong theoretical bent.

The February 2017 issue will include the presidential address by Patrick Manning and articles on Atlantic slavery, capitalism and the American West, and religion in early 20th-century China, as well as a review essay on a history website.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.