The December issue of the American Historical Review features two articles: one on astrology in 18th-century Russia, the other on the place of Jerusalem’s Western Wall in Zionist iconography. We also have an AHR Roundtable commissioned by the previous editor, Robert Schneider, on the ever-pressing question of how civil wars come to an end. The issue also contains five featured reviews and our regular book review section.

Articles

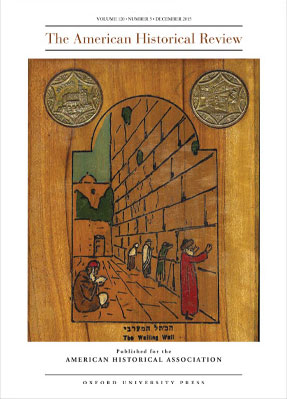

A site of Jewish prayer for more than a thousand years, the Western Wall (or “Wailing Wall”) in the Old City of Jerusalem became a popular subject in 19th-century art and travelogues, reflecting Europeans’ and Americans’ growing interest in Palestine and in the Jewish connection to it. Into the 1920s, the “Jews’ Wailing Place” remained an evocative symbol of this bond, although the modern Zionist movement was often ambivalent about the site. With the rise in Jewish-Muslim tensions, however, the site began to reflect the fundamental changes in a nation that was now turning to it as a place not only for prayer, but for a range of civil rituals and political demonstrations. With its new imagery of sacrality and strength, the wall became a powerful symbol for the budding nation. In “Wailing Walls and Iron Walls: The Western Wall as Sacred Symbol in Zionist National Iconography,” Arieh Bruce Saposnik explores how the wall was transformed as both site and symbol, providing a new perspective on nationalism and its complex relationship with religious traditions. Passover Haggadah, 1926, with artwork by Ze’ev Raban. The medallions at the top show the Tower of David (left) and the wall.

In “On the Cusp: Astrology, Politics, and Life-Writing in Early Imperial Russia,” Ernest A. Zitser and Robert Collis offer a rare, microhistorical glimpse into a complex and still-misunderstood past. Analyzing the profound faith in astrological projection held by a top-ranking member of 18th-century Russia’s ruling nobility, Zitser and Collis throw into sharp relief that elite’s claim on belonging to the modern world. As the authors demonstrate, the ancient belief in mystical connections between macrocosm and microcosm persisted among the top ranks of imperial Russian society into the age of Enlightenment. This is seen in the practical concerns of a recently ennobled royal servitor just as Russia’s political institutions, publishing industry, and scientific community reached a turning point. The life experience of one individual, as well as the ideas, encounters, and practices that shaped political behavior at this moment, allow Zitser and Collis to reassess the role of Peter the Great in modernizing Russian life and political culture. This analysis helps reframe the debate about the temporal and geographical origins of “Enlightenment” and integrates the study of Petrine Russia into a transcultural history of science and subjectivity.

Arieh Bruce Saposnik’s timely “Wailing Walls and Iron Walls: The Western Wall as Sacred Symbol in Zionist National Iconography” examines another important site of the interplay between the traditional and the modern. Jewish nationalists first viewed the wall as a symbol of exile and the destruction of a people. During the 1920s, however, the wall as site and symbol became a national icon and focal point of a national-religious conflict in Palestine. This moment of transformation offers an unusual vantage from which to explore the workings of conflicting representations, religious sentiments, efforts to create a national liturgy, international diplomacy, and internal competition between factions of a national movement. As a study of the metamorphosis of a traditional symbol, the article offers fresh insights into the relationship between nationalism and religiosity, secularization and resacralization. Examining one component of a broader Zionist effort to create a secularized, national version of the sacred, Saposnik advances new perspectives on nationalism and its complex relationship with religious traditions in a secular age.

As a companion to Saposnik’s article, the editor’s “In Back Issues” essay examines how the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has been treated in past issues of the AHR.

AHR Roundtable

The AHR Roundtable “Ending Civil Wars” takes up what appears to be a ubiquitous topic from a novel angle. Though civil wars capture the attention of historians in virtually every field, we prove far more alert to their causes, dynamics, and consequences than we do to how they are brought to a conclusion. Victors and vanquished in a civil war must learn to live together again as neighbors and fellow citizens. To explain how this has occurred, from classical Rome to modern Afghanistan, 10 historians each provide a short essay on civil wars in their area of expertise. The result is a wide-ranging discussion about the nature of civil conflict and the myriad ways human beings have made an almost always fragile peace.

In “Ending Civil War at Rome: Rhetoric and Reality (88 BCE–197 CE),” Josiah Osgood considers how the major civil wars of classical Roman history (c. 100 BCE–200 CE) ended. He concludes that the emergence of Rome’s first emperor, Augustus, came to represent the rhetorical opposite of—and safeguard against—civil war. Comparative study of civil wars in imperial Rome, Osgood maintains, can explain the centrality and endurance of the myth of Augustus as an “ender of war” in Roman historical memory.

In “Ending the French Wars of Religion,” Allan A. Tulchin uses political science literature to gain insight on how these recurrent 16th-century sectarian wars finally ended. Tulchin argues that a “learning curve” eventually made peace possible after the Edict of Nantes (1598). Not only was the edict enforced by a decisive military victory, but Henri IV’s previous experience as a leader of an insurgent party led him to adopt a more open leadership style.

A similar conflict broke out across the English Channel during the next century. In “From Peacemaking to Peacebuilding: The Multiple Endings of England’s Long Civil Wars,” Matthew Neufeld contends that the 17th-century English civil wars ended only when former combatants or their descendants decided they could work together. Lasting civil peace was not built in England until the 1690s, as a direct consequence of the 1688–89 revolution. The war to defend the revolution from its foreign enemies, Neufeld argues, finally bridged partisan and denominational lines.

Three essays consider 19th-century civil wars. In “Where the War Ended: Violence, Community, and Commemoration in China’s 19th-Century Civil War,” Tobie Meyer-Fong describes how messianic visions and social dislocation inspired civil war in the central and southern provinces of Qing China. Militarily, the war ended when the capital was reoccupied by regional armies loyal to the dynasty. Yet conflict between rebels and loyalists continued through commemorations and deliberate acts of erasure by provincial governors, local elites, and the imperial court. Meyer-Fong illuminates a common theme: the long-lasting efforts to impose narrative and commemorative closure on civil war, which thereby paper over its lingering physical, political, and emotional effects.

In “Diminished Sovereignty and the Impossibility of ‘Civil War’ in the Modern Middle East,” Ussama Makdisi explores the apparent resolution of the great sectarian crisis between Muslim and non-Muslim that unfolded in the Ottoman Empire, suggesting that much can be gained from juxtaposing it with the resolution to the far better known American Civil War. In each, the quintessentially 19th-century problem of shifting from a system of overt discrimination to one emphasizing equal citizenship was critical. Makdisi observes that in the Ottoman context the transformation was cast in religious terms, while in the United States the discourse was racialized. A major difference was the enduring role Western imperialism played in shaping politics in the modern Middle East.

Turning directly to the United States, in “Finding the Ending of America’s Civil War,” William A. Blair argues that in contrast to contemporary conflict resolutions, the American Civil War featured no third-party intervention, no negotiated settlement, and no discussion of human rights resulting in either reparations or punishment in civil courts. Finding the ending of the Civil War in the United States can be difficult, leading to the unfortunate conclusion that force rather than reason is more effective in holding fractious countries together.

The remaining Roundtable essays take up the lingering aftereffects of civil wars in the 20th and 21st centuries. In “How Did the Spanish Civil War End? . . . Not So Well,” Sandie Holguín argues that Spanish Republicans’ surrender in April 1939 did not end this conflict. Instead, Francisco Franco’s Nationalists initiated a decades-long war of violent occupation and terror against the losing side. This conflict demonstrates that although a war might be officially over, violent purging to maintain the victor’s power and legitimacy can seriously prolong a civil war. Memories of atrocities and postwar terror induced a collective shell shock that would end only after Franco’s death in 1975. Even today, those who claim to be the guardians of the war’s memory deploy that memory rhetorically in the Spanish public sphere.

Looking at another conflict pitting left against right, in “How Did the Civil War in El Salvador End?” Joaquín Chávez reconsiders the peace negotiations that ended the 12-year war between the government of El Salvador and the insurgent Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) in 1992. According to Chávez, the transformation of the FMLN from one of the most powerful insurgencies in recent Latin American history into a legal political party ultimately enabled a political settlement that ended the war and ushered in liberal democracy. Paradoxically, the erstwhile leftist insurgents also facilitated the neoliberal restructuring promoted by the former right-wing government and multilateral financial institutions in the 1990s.

The last two essays address conflicts far less explicable with the coherent political narratives of left and right shaping many 20th-century civil wars. In “Lost in Transition: Civil War Termination in Sub-Saharan Africa,” William Reno identifies competing narratives of “liberation war” and “criminal war” in the region, with no clear boundaries between peace and war and no decisive end to civil wars. As a case study, Reno analyzes Liberia’s early 1990s civil war; as he argues, the National Patriotic Front of Liberia asserted a “liberation war” narrative just as international support for a “criminal war” narrative gained strength. The latter, Reno contends, impeded a decisive civil war termination.

Concluding the Roundtable with a civil war that recurs to this day, Abdulkader Sinno’s “Partisan Intervention and the Transformation of Afghanistan’s Civil War” points out that the US-led coalition’s intervention in Afghanistan raises fundamental questions about the nature of civil war in an age of increased globalization. As the US-led occupation shows, contradictions within outside interventions limit their ability to build robust state institutions and defeat resistance. Like Reno, Sinno concludes that such partisan interventions tend to transform and extend civil wars rather than bring them to a peaceful resolution.

The Roundtable closes with a general meditation on the phenomenon of civil wars by David Armitage. As Armitage writes, many observers have claimed that “of all wars, they are the worst, and that they are so terrible because they seem interminable.” Armitage concludes that civil wars are indeed the most resistant to a lasting peace, leave the deepest wounds on the body politic, and linger the longest in social memory, as many of the contributions to this stimulating Roundtable indeed suggest.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.