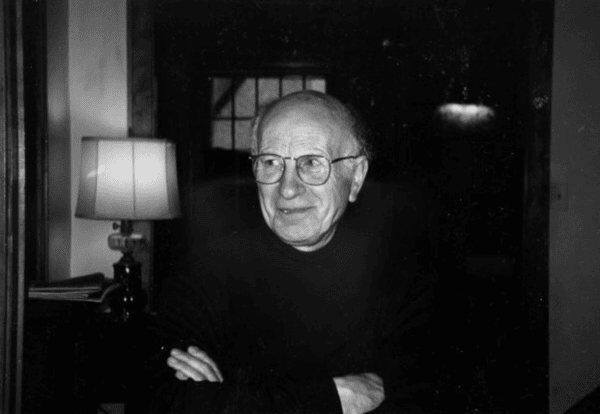

Paul Jeffrey Meyvaert. Courtesy of the Meyvaert family

At the end of his autobiography, Jeffrey’s Story (2005), Paul Jeffrey Meyvaert explained that he no longer believed in a life after death: “If I am proved to be wrong I shall be delighted, and immediately seek out my dear Bede to begin a long chat with him. But even without belief in an immortal soul I find that life remains wonderful, and human love and friendship the gifts I treasure most while I continue living on this very, very old and fragile globe.” When Paul Meyvaert died suddenly, at home, on October 6, 2015, he passed away as he would have wished: still deeply absorbed by his endless curiosity about the world around him, still engaged and interested in the scholarly problems that had preoccupied him during his long career, and still buoyed and enriched by the many friendships he cultivated.

Jeffrey Meyvaert was born on November 12, 1921, in the United Kingdom, to a British mother and a Belgian father. He barely knew his father and was raised in England, Belgium, and Ireland by a deeply religious mother who pushed him toward a religious vocation. He took on the name Paul when he first entered the Benedictine order. Most of Paul’s life as a monk was spent at Quarr Abbey on the Isle of Wight. There Paul became a scholar, largely teaching himself the languages, technical skills, and historiography of a medievalist. His first scholarly article appeared in 1955, setting off a long train of essays. He started with problems of Benedictine history, before widening his focus to other issues of textual identification and religious history. For instance, he made a significant discovery vindicating a key witness to the mission to the Slavs of Saints Cyril-Constantine and Methodius. In 1959, Paul followed this with his important examination of the supposed autograph manuscript of the Rule of Saint Benedict. In these early years, Paul produced studies of two figures who would continue to dominate his scholarship throughout his life: Bede and Gregory the Great, both monks, and both with deep ties to England.

Paul’s life changed fundamentally in May 1957, when a young American medievalist named Ann Freeman visited Quarr Abbey to discuss her research with a senior monk and scholar whom Paul assisted. Paul and Ann began an intense epistolary correspondence that developed into a great romance. In 1965, Paul left Quarr Abbey, and after he had received a papal dispensation from his monastic vows, he and Ann were married in Pittsburgh on February 4, 1967. After a quarter century as a monk, essentially his entire adult life to that point, Paul had to learn how to live in a radically new world. With no formal academic training, he nonetheless made a career as an important scholar and editor, and started his new life as a husband, and eventually as father to Jenny, the daughter he and Ann adopted.

The first formal academic position Paul Meyvaert held was as an art history librarian and lecturer at Duke University. In 1970, Paul was offered a tenured professorship in medieval studies at Duke, as well as the positions of executive director of the Medieval Academy of America and editor of its flagship journal, Speculum. After much soul-searching, Paul and Ann moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1971 and bought the house on Hawthorne Park where Paul spent the rest of his life. At the Medieval Academy, Paul came to play a guiding role in medieval studies in the United States, through his careful advocacy for medieval studies as a whole and his inspired editing of Speculum. Paul spent 10 years editing Speculum and overseeing the Medieval Academy, years as productive for him as they were for the institution. He continued to be involved at the academy, if only on regular visits to the offices, until his death.

A master of the form of the journal article, Paul Meyvaert produced over 70 scholarly studies during his lifetime. His primary subjects were medieval ideas of authorship (forgery, publication, and so on), iconography, textual criticism based on careful manuscript analysis, and the nature of medieval monastic life. He was an early adopter of computerized philology, which he used to resolve a number of contested identifications of authorship. He collaborated with Ann on a new critical edition of the Libri Carolini, an extraordinary treatise on images and their role in Christian practice prepared for Charlemagne. Now known by the more accurate title Paul and Ann bestowed on it, the Opus Caroli (“Work of Charlemagne”), the new edition definitively established its main author as Theodulf of Orléans, not Alcuin, as others had held. In his last years, Paul contributed many new insights into the imagery in the chapel Theodulf built and a damaged Anglo-Saxon monument, the Ruthwell Cross. Visitors to Hawthorne Park of late would often be treated to his 3-D paper model of the Ruthwell Cross and his printouts of idiosyncratic vocabulary in the writings of Theodulf. A precise and careful scholar, Paul had a gift for extracting just the key detail from his reams of painstaking research to shed light into a corner of the medieval past.

Paul lost his beloved Ann in 2008. He is survived by his daughter, Jenny, and her partner, Janie Cron, as well as by the legions of friends he made across the globe and the scholars whose work was enhanced by his insight and his generosity. Donations in memory of Paul may be made to the Paul J. Meyvaert and Ann Freeman Meyvaert Fund at the Medieval Academy of America.

Jennifer R. Davis

Catholic University of America

Michael McCormick

Harvard University

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.