To be perfectly honest, my course The Cold War and the Spy Novel grew out of a juvenile obsession with James Bond films that lasted well into adulthood. I once shared my interest in teaching how Ian Fleming’s novels became films with my mentor Richard Stites of Georgetown University (in a bar), and he thought it was a great idea but suggested expanding the source base. It seemed for a while during the 1990s that this would remain an interesting, but purely academic project.

In the late 1990s, I noticed how effortlessly Russian and American politicians dusted off and redeployed Cold War stereotypes when it suited their needs. Then 9/11 happened and then the war in Iraq. In this “war on terror,” with intelligence advisers claiming that uncertainties like the existence of Iraqi WMD were actually “slam-dunk cases,” it was clear that public opinion formation, social mobilization, and fiction making were again deciding the fates of millions. There is something much deeper than history in stereotyping, I thought; there’s something profoundly human about it. My juvenile obsession matured into a serious research interest.

When I gave The Cold War and the Spy Novel its first try in the spring of 2010, it proved to be wildly successful and has become an annual ritual at American University in Washington, DC. I follow a structure of one lecture and one seminar per week. The lectures set the historical context for the novels, which gives even the most pedestrian page-turners surprising depth and educational value while keeping the students entertained and engaged.

Student feedback has been encouraging. AU alumna Sarah Adler noted, “Using spy novels not only makes the material more entertaining and sometimes easier to read than a monograph, but also demonstrates to students that there is more to history than analyzing traditional academic works.” Alex Keene corroborated her thoughts: “Spy fiction provides a unique perspective on the Cold War, precisely because it offers a common man’s perspective on important events, at the time of their occurrence.” Indeed, espionage novels double as primary and secondary sources.

Using works from both sides of the Iron Curtain, my course explores the process of constructing stereotypes, the social role that espionage fiction played in the West and the East, its accuracy in terms of depicting the espionage community, and the relationship between literary fiction and what I term Cold War epistemology—politicized intelligence and public opinion formation. I change the syllabus every year because the course doubles as research for my second book project, provisionally titled Superpower Subconscious: The Cold War and the Spy Novel.

Teaching about the Cold War in Washington is an added blessing, given that so much of it unfolded on this city’s streets, which are littered with Cold War landmarks. To give just one example, AU’s student shuttle runs right past 4100 Nebraska Avenue, the house in which Kim Philby lived while he was stationed in Washington. I love to hear the gasps of surprise when I finish the story of the Cambridge Five and then show my students the house that every single one of them has passed hundreds of times.

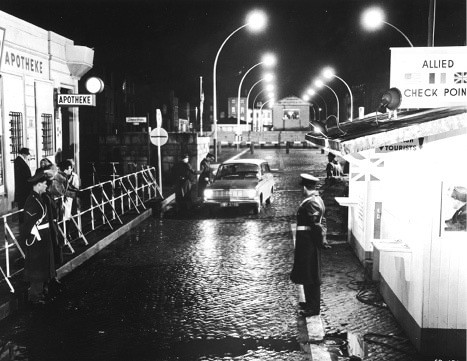

Courtesy of The Criterion Collection (www.criterion.com)

Checkpoint Charlie in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965). The Berlin Wall provides a clear line between East and West for John le Carré’s characters to cross as they discard loyalties or run for safety. Less clear are the moral distinctions between the rival intelligence services.

Various scholars have hinted at the importance of espionage fiction to the history of the Cold War. And yet the history of intelligence and the spy novel remain poorly integrated into Cold War studies and the broader history of the 20th century. Some scholars have compared the intelligence community’s files to a “nation’s unconscious.” If you buy this argument, then the espionage genre functioned as a form of psychoanalysis, with novels as parables loaded with collective wishes, hopes, fears, and unarticulated anxieties. For historians, these works can yield rich veins of primary source material because in addition to being entertaining, spy novels have also documented their era by reflecting geopolitical realities and the evolution of national identities.

An Anglo-Saxon phenomenon, the espionage genre branched off from detective novels in the late 1890s when rising literacy, a vibrant press, and cheap books created a feedback loop affecting state policies. England’s first professional spy writer, William Le Queux, contributed to the spy mania that led to the establishment of the Secret Service Bureau (the predecessor of MI5 and MI6) in 1909. Some of the evidence heard by the government committee that suggested its creation came from his books. The first British spy novels were actually about counterespionage because it was morally justifiable (British gentlemen don’t spy, but do catch foreign spies). It was also closest to standard detective work, which was already popular as the subject of fiction in Britain. The anxieties of imperial overreach contributed to the genre’s popularity, but the Great War made it a literary staple. The enemies changed—the French in the 1890s, then the Germans, then the Bolsheviks and the Nazis—but the basic idea of defending home and hearth remained the same. With the Bolsheviks, however, a new relentless global struggle ensued without front lines, without rules, and with an enemy who infiltrated societies and undermined them from within.

The Soviets developed their own espionage genre in the 1920s, with writers such as Marietta Shaginian, but the genre’s creativity came to an end during the 1930s, when depicting Soviet agents unmasking foreign plots against the Soviet Union settled into a predictable and formulaic pattern. One would think that the Soviets would have developed a vibrant espionage novel tradition, but they did not because writing about the NKVD and then the KGB was prohibited, while probing a closed society’s secrets was quite simply discouraged. Although the Soviets published spy novels, they were chronologically stuck in the era of the civil war, the 1920s, and then the Second World War. One exception to this rule was Yulian Semyonov, who wrote espionage fiction actually set in the time of his books’ publication. But too few of them have been translated into English, although they offer a fascinating flip side of the Cold War struggle.

The Cold War reinvigorated the espionage genre and pulled American authors into it. Discussing these books with students always brings us back to the current debate about the extent of the security state. Could it be that the moral and ethical compartmentalization between the tools of the Cold War and the freedoms they aimed to protect may have been illusory? The Cold War’s global peacetime espionage conflict corrupted even the most open societies by forcing them to compromise the civil liberties they championed. Fought with propaganda and fear, the Cold War empowered state-sponsored fictions to influence reality on an unprecedented scale. And as the Edward Snowden affair recently demonstrated, the end of the Cold War did not mean that espionage was over as a trade or a subject of popular fiction.

The Cold War’s global peacetime espionage conflict corrupted even the most open societies by forcing them to compromise the civil liberties they championed. Fought with propaganda and fear, the Cold War empowered state-sponsored fictions to influence reality on an unprecedented scale.

Film is an integral part of the course, and I always assign movies based on the spy novels to demonstrate how scripts politicized (and sometimes even reversed) the original material. For example, Graham Greene’s The Quiet American (1954) was critical of US support for the French colonial war in Indochina. Together with Lederer and Burdick’s The Ugly American (1958), it registered the dawning struggle of the superpowers to coopt decolonization. Reflecting the rising stakes in this game, Joseph Mankiewicz’s 1958 film The Quiet American turned Greene’s plot on its head by making the novel’s protagonist, Thomas Fowler, a dupe of a Viet Minh disinformation campaign that unjustly accused Alden Pyle of being a US government agent. It worked the other way, too. Alastair Maclean’s Ice Station Zebra (1963) was anti-Soviet, but the 1968 film reflected the dawn of détente and ended on a much more positive note.

American presidents have enjoyed a lengthy love affair with espionage fiction. FDR enjoyed British spy novels. John F. Kennedy included Ian Fleming’s From Russia with Love in a list of his 10 favorite books. And Ronald Reagan called Tom Clancy’s TheHunt for Red October “unputdownable.” During a Christmas shopping trip in December 2013, President Obama purchased a copy of Jason Matthews’s new spy thriller Red Sparrow. Drawing on a rich legacy of Cold War stereotypes, the novel rebrands Vladimir Putin’s Russia as the new Soviet Union. Written before the Ukrainian crisis, the novel fully mirrors the current interpretation of the Kremlin’s policy inside the Beltway and offers an insight into why the Obama administration “reads” Russia the way it does.

The world may not be entering a new cold war, but Matthews demonstrates the persistence of Cold War epistemology as a form of policy-driven intelligence and knowledge production that reflects the interests of its customers more so than reality. Indeed, both the West and Russia are once again entering a historical stretch when espionage fiction reflects and even contributes to imaginary narratives about national identities, geopolitical intentions, and even “facts on the ground.” Welcome back to the wilderness of mirrors. Here’s to job security.

is assistant professor of history at American University in Washington, DC, and executive director of AU’s Initiative for Russian Culture.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.

The American Historical Association welcomes comments in the discussion area below, at AHA Communities, and in letters to the editor. Please read our commenting and letters policy before submitting.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.