As one of my senior history majors was working on his capstone thesis paper, he shared with me that he never felt comfortable writing an argument. He could easily research and write on a topic, but he still felt intimidated by asserting an interpretation of the sources and committing to a claim. He is not alone. I have often seen advanced undergraduate students struggle with this limitation. They understood how to find and analyze sources but were daunted by the prospect of asserting a clear argument and carrying it through the research and revising process.

With immediate feedback, Elizabeth George sees immediate results in students’ improved work and their learning.

I recognized that the time to address this student’s concern was not senior year but in lower-level classes where there was more room to fail. Of course, students in my survey classes make arguments on exams or in papers, but they don’t have the pressure of sticking with and developing an argument over the course of repeated revisions and additional research like seniors do with a capstone. A student in a survey class might lose points for a weak argument, but do I require them to revise a midterm exam for another round of feedback? No.

I wanted to move even one step further back from the comprehensive assessment of an essay or paper and help my students become comfortable with wandering an archive—as ShawnaKim Lowey-Ball explains in “History by Text and Thing” (Perspectives on History, March 2020)—developing an argument, and then receiving critical feedback and revising, all in a low-stakes setting. I therefore developed an in-class activity and process for giving immediate feedback. Not only did this increase active learning in class, but it had the added benefit of reducing my grading load.

I targeted in-class assignments where students wrote paragraph-length responses that included an argument and a brief analysis of evidence. These writing assignments were short enough that I could give feedback immediately, especially if students worked in groups. Image analyses or comparisons, evaluations of grouped thematic sources, film or museum exhibit responses, and similar evidence analysis assignments all worked well. As Alison Burke has recommended, students work in groups of three or four, with clearly defined group roles such as leader, writer, and researcher, before digging into the sources. The assignment instructions outlined several clear steps in the research process and then provided a prompt to make an argument derived from the investigation. Typically, this assignment would take about 20 minutes for a group to complete.

Image analyses or comparisons, evaluations of grouped thematic sources, and film or museum exhibit responses all worked well.

As students completed the prompt, I circulated the room to read their draft responses on the group leader’s computer screen. These drafts needed to include a clear argument and brief analytical discussion of either specific sources or groups of sources. I read the paragraphs quickly, focusing on the argument’s clarity and persuasiveness, and how effectively students supported arguments with robust source analysis. I then would talk through specific feedback with the group, without assigning a grade. I could push them to develop the argument by making it more specific or significant or by connecting it more closely to their source analysis. Students would then revise their answers. I might ask them to show it to me again for another round of feedback if the original was particularly weak. Finally, the group would submit their final response for a grade. Usually, I could complete the grading in just a few minutes, with most groups receiving full credit.

As I developed this assignment, I realized several parameters were necessary for the immediate feedback approach to run smoothly. First, the prompt must be both clear and thorough. This would allow me to evaluate the response quickly and focus only on the effectiveness of the argument and evidence, not on whether students understood the task. The prompt also needed specific instructions about using sources to support the claim.

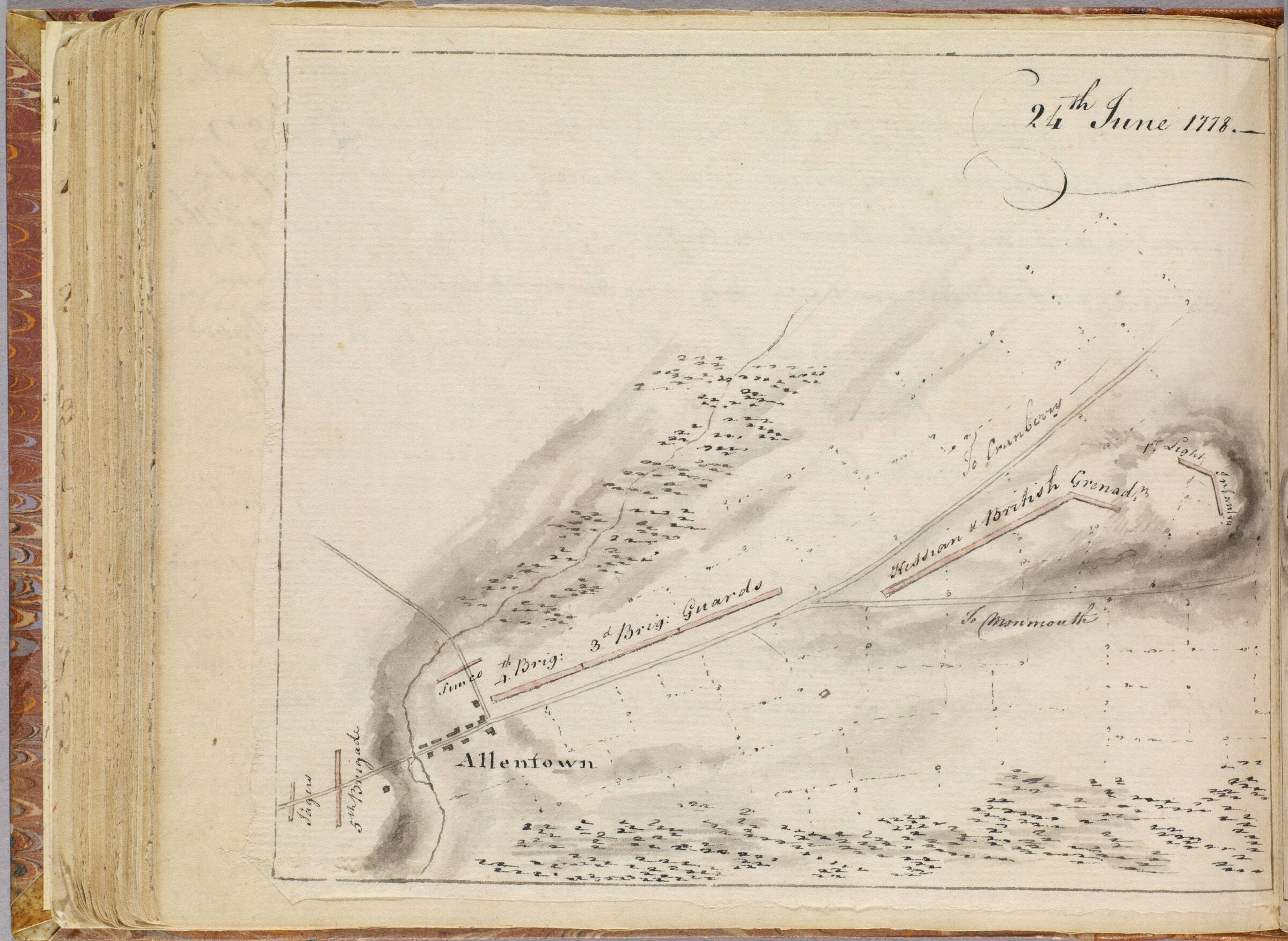

For example, in a lower-level class that examined the journals of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s Corps of Discovery (1804–06), the prompt could be “Read all the journal entries for one month of the expedition. Based on the journal entries, to what extent was the expedition an assertion of power over the new territories?” In a more advanced class, the prompt might be more open-ended, such as “Read all the journal entries for one month of the expedition. Based on the journal entries, how did the members of the corps interpret their mission? Support your response through an analysis of the journals.”

With immediate feedback, I observe in real time as my students move from simply trying to complete the assignment with little care for the quality to realizing that a successful argument convinces the reader. I could show students why their argument wasn’t convincing and allow them to reframe or search for new evidence. As we worked through these immediate feedback sessions, students were excited to see whether their initial argument would make the cut. As they watched me reading their answers on their computer screen, they would read along and sometimes try to make changes further along in the paragraph as they spotted potential weaknesses. Often there would be high fives among the group when their argument was accepted. The process was enriching for students as they worked to fully complete the assignment, and it was revitalizing for me as the instructor as I could see students responding to my feedback.

While there are useful benefits to this approach, there are also potential drawbacks. Positively, I found this method easy to deploy for single assignments or in classes for which I did not want to overhaul the whole course’s grading structure. In addition, as students saw that their responses were evaluated in real time and as they perceived my method in evaluating their work, they took the assignment more seriously. In the past, I gave feedback through the learning management system that students might never look at. With immediate feedback, I could see right away how well students achieved the learning goal, and I could redirect and reteach in class as needed. I found that more students received full credit for the assignment and that the grade reflected the reworking and communicating that happened in class. Finally, I enjoyed the opportunity for direct, in-class instruction with individuals or groups. These types of low-stakes interactions helped me build rapport with my students and helped them become comfortable with seeking and receiving feedback.

Students were excited to see whether their initial argument would make the cut.

However, though immediate feedback moves quickly, especially with clear instructions, I learned that there was a limit to how many responses I could evaluate. In a 50-minute class session, it was best if there were no more than 8 to 10 groups. If I had a teaching assistant, that would have easily doubled the number of evaluations I could give. I found that this approach works best in multistep assignments, so that all groups do not seek evaluation at the same time. This process also required substantial energy from me. The flurry of giving a lot of feedback in a short period of time may not work well with some teachers’ styles, although others will feel supremely energized.

Giving immediate feedback is more difficult in classes larger than 35 students but not impossible. In larger classes, the instructor could lead the whole class through a review and evaluation of several samples, perhaps with a rubric. Then teachers could outline a process for either peer or individual feedback, with the goal of rewriting. In this case, students might submit both their original and revised answers. However, while students would have the benefit of feedback and revision, the goal of reducing instructor grading might not be fully achieved in a larger class.

College teachers have long noted the benefits of providing feedback for the purpose of revision, as well as of inviting students to join both the research and assessment process. In Super Courses, Ken Bain discusses the benefits of peer instruction in group problem-solving, while Carla Vecchiola’s “Digging in the Digital Archives” examines how giving students freedom in archival research at the introductory survey level results in deeper student engagement. Other instructors might opt for an “ungrading” system, giving students the option to revise and resubmit tests or paper drafts; specifications grading, in which students work to meet certain thresholds; or specific tools such as the Immediate Feedback Assessment Technique, used for objective assessments. The development of various AI-enhanced grading tools might alleviate the grading load; however, in my experience, the mere presence of the feedback does not necessarily mean students will look at it, reflect on it, and adjust their future work. Using immediate feedback a few times each semester brought the proven benefits of revision or of proficiency-based grading to lower-stakes assessments. I hope that these early interventions will help students feel more confident in their argumentative skills as they progress through the curriculum.

While student learning improved, so did my own satisfaction with the lesson’s effectiveness. I felt more fulfilled when I spent my time giving feedback that students actively responded to. I left the room feeling confident that I had communicated well with my students and guided them toward deeper understanding, with the added bonus of leaving with very little to grade. I enjoyed creating meaningful connections with my students as we went back and forth over their responses, and especially valued the opportunity to connect with students who might not otherwise speak up. And when these students reach their senior capstone thesis, I hope they feel better prepared to make their own intervention in their field of choice.

Elizabeth George is professor of history at Taylor University and author of Engaging the Past: Action and Interaction in the History Classroom (Rowman & Littlefield, 2024).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.