The September 2024 issue of the American Historical Review features articles and forums that rethink approaches to environmental, humanitarian, and welfare history, and includes pieces on historical fiction, archives and libraries, and history education.

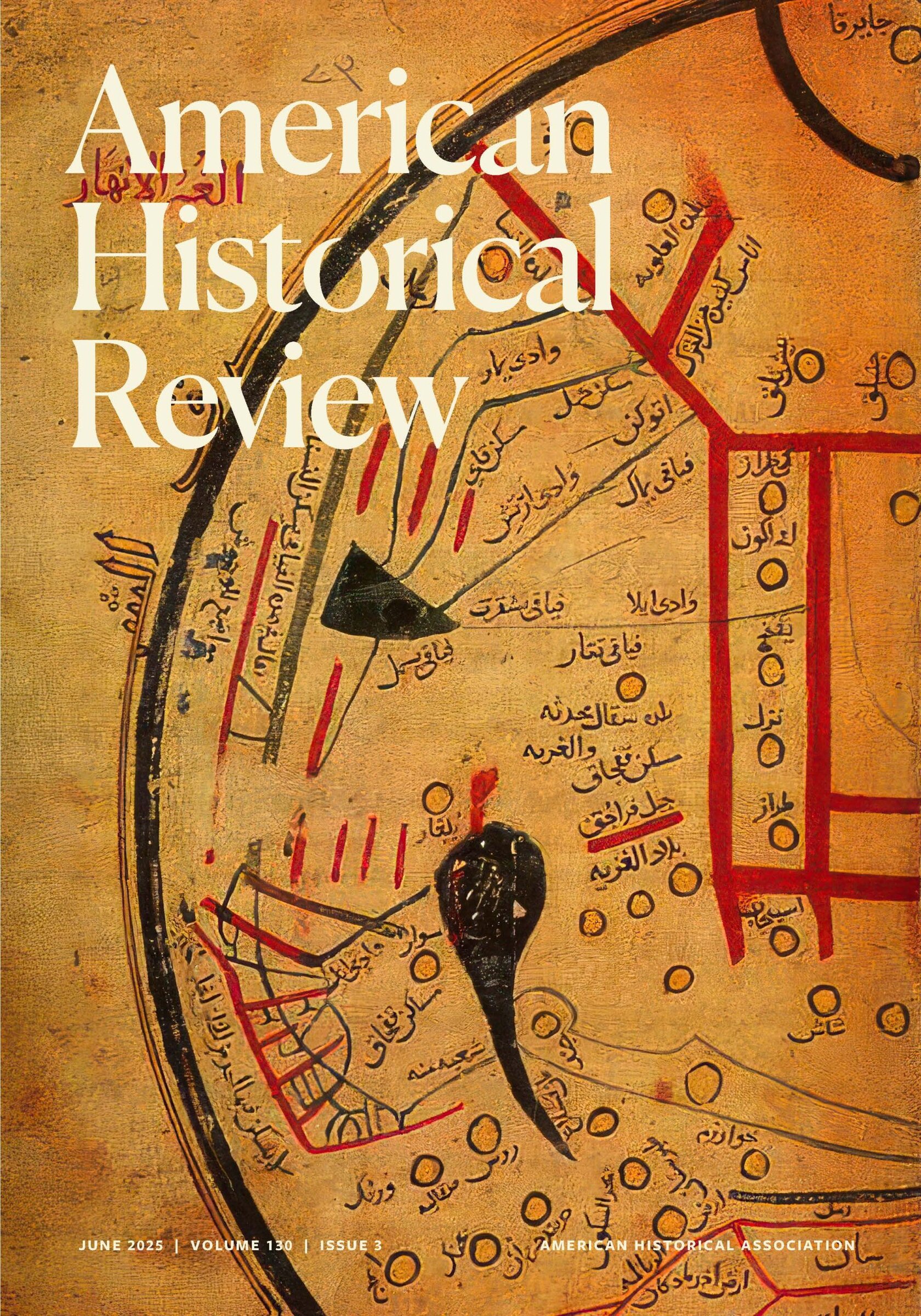

The late 19th-century cotton dress that floats across the cover of the September AHR offers a marvelous illustration of the diversity of histories and methods that make up this issue of the AHR. In the #AHRSyllabus module “A Case for Objects: Material Culture in the History Classroom,” Sarah Jones Weicksel introduces an object analysis worksheet to help students create a biography of a single object and ask historical questions about the object’s life cycle. She offers a short biography of the dress on the cover of this issue of the AHR to illustrate the kinds of stories objects can tell. Image: Dress, 1872, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Acc. No. 2003.426a, b.

In “Looking for the Soul in Environmental Lament: Civil Religion, Political Emotion, and the Handling of the Earth in the New Deal Era,” Michael G. Thompson (independent scholar) and Clare Monagle (Macquarie Univ.) explore the history of New Deal environmental policy and practice, in particular the use of biblical language and imagery in the New Deal soil jeremiad. Thompson and Monagle frame the environmental “sins” of this lament, namely land overuse and soil erosion, against the backdrop of the growing convergence of ecumenical missionaries and conservation efforts. They argue New Deal environmentalism defies typical categorization used in environmental politics and invite an interfield discussion of religious and environmental methodologies.

Melanie Schulze Tanielian’s (Univ. of Michigan) “‘We Found Her at the River’: German Humanitarian Fantasies and Child Sponsorship in the Eastern Mediterranean in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries” discusses German humanitarian work in the late 19th century. She challenges previous scholarship that focused on Anglo-American humanitarianism and traces the influence of pious German efforts, particularly its openness to international and ecumenical collaboration and the promotion of individual development, on modern humanitarianism’s ideologies and practices. She highlights the success of the Armenisches Hilfswerk (Armenian Relief Works) one-to-one child sponsorship program to promote an imagined humanitarian community among the evangelical moral counterpublic and traces its contribution to interwar international humanitarian practices.

In “Carceral Recycling: Zero Waste and Imperial Extraction in Nazi Germany,” Anne Berg (Univ. of Pennsylvania) investigates the use of carceral recycling—camp-based waste labor—in the Nazi regime. She traces connections between Nazi paranoia about resource limitations and ideas about cleanliness and order, and demonstrates how waste utilization lay at the heart of the system that exploited camp and prison labor in the service of racial purification and imperial expansion. Such framing, Berg argues, firmly grounds the Nazi system of plunder and murder in the trajectory of Western imperialism and its enlightened rationality.

The History Lab opens with a forum of 21 reviews of contemporary historical fiction, including novels, graphic narratives, films, and plays that take on historical issues across time and space. Instead of focusing on historical veracity, reviewers were asked to consider what historical fiction can tell us about the past that other works of history cannot, the innovative forms and voices through which these works engage with their readers, and what reviewers saw as the gains, and losses, of these fictionalized histories. Taken together, we hope these reviews will offer readers a kaleidoscopic perspective on the making of historical fiction today.

New histories of the American welfare state make up a second forum in the Lab that foregrounds the work of three early career scholars who met as National Fellows in the University of Virginia Jefferson Scholars Program: Salem Elzway (Univ. of Southern California), Salonee Bhaman (New-York Historical Society), and Bobby Cervantes (Harvard Univ.). Their doctoral research self-consciously explored what they saw as new approaches for understanding the operations of the welfare state, with Elzway examining the rise of artificial intelligence and the industrial robot, Bhaman the politics of care in the era of HIV/AIDS, and Cervantes the social lives of communities along the US-Mexico border that are among those experiencing the most extreme concentrations of poverty in the United States. Linda Gordon (New York Univ.), Alice O’Connor (Univ. of California, Santa Barbara), and Karen M. Tani (Univ. of Pennsylvania) offer commentary to situate these essays in the longer arc of welfare history.

Gabrielle Dean’s (Johns Hopkins Univ.) “Ghost Records in the Archival Empire: Africana Cultural Heritage Stewardship at Historically White Institutions” returns the Lab to one of its central concerns, the connections between archives and libraries and the work we do as historians. Drawing on her expertise as a curator of rare books and manuscripts, she discusses how interrelated financial, epistemological, and cultural mechanisms contribute to persisting challenges for collecting African American rare books and archival materials in historically white institutions. Dean advocates for sustained and multifaceted collaborations with archivists at historically Black colleges and universities to support broad efforts to build more robust primary collections of Black history, along with collecting practices informed by community participatory archives programs.

What can historical fiction tell us about the past that works of history cannot?

The September Lab includes two new modules for the #AHRSyllabus. In “Good Question: Right-Sizing Inquiry with History Teachers,” AHA researchers Whitney E. Barringer, Scot McFarlane, and Nicholas Kryczka develop a set of guidelines for asking students questions about the past that reveal the motives of historical actors, address the interplay of structure and agency, and investigate the collision of long-run continuities and sudden contingencies. For their module, they trace curricular initiatives around “inquiry” from the late 19th century to the present to suggest practices for today’s classroom that allow, as they put it, “students to see what history can do for them, and what they must do for themselves.”

Sarah Jones Weicksel’s (AHA) module, “A Case for Objects: Material Culture in the History Classroom,” provides an easy-to-use method and set of exercises for exploring history through objects. She provides an object analysis worksheet that can help students create a biography of a single object and ask historical questions about the object’s life cycle; a lesson plan that interweaves an array of objects, images, and texts as sources through which students can analyze Northern civilian encounters with the American Civil War; and a “found objects” activity, in which ordinary objects are used to introduce students to doing history through material culture.

Three History Unclassified articles close out this issue’s Lab. In “Through the Valley of the Shadow of Death,” Anthony David (independent scholar) draws on his experiences writing a biography of a German Benedictine monk to reflect on how historians can unwittingly propagate inaccuracies. A central figure in the monk’s life, he came to believe, was a Nazi war criminal. But while working on this book, David encountered new evidence that suggested that might not be so, which led him to reassess his work and challenge his own underlying beliefs. Melani McAlister’s (George Washington Univ.) “Promises, Then the Storm” crosscuts between observations about the first months of the Gaza war in the fall and winter of 2023 and her ongoing work on the history of Palestinian and Third World solidarity movements in the United States during the 1980s, particularly the place of music and art in them. In “My Brother’s Story,” Nico Slate (Carnegie Mellon Univ.) draws on his experiences as a white historian writing a memoir on the life and death of his mixed-race older brother, along with the work of other memoirists and historians, to discuss the challenges of writing about race, memory, guilt, and gratitude.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.