“Don’t tell me it doesn’t work—torture works,” then presidential candidate Donald Trump said at a February 2016 campaign event in Bluffton, South Carolina. “Okay, folks, torture—you know, half these guys [say]: ‘Torture doesn’t work.’ Believe me, it works, okay?” At the time, I was finishing my recent book on Americans and human rights in the 20th century, and Trump’s repeated defense of torture, like so many of his pronouncements, struck me as relics of the past. Like many, I did not see the Trump presidency coming. Now less than one week into his presidency we already have a draft executive order that would reopen the “black site” prisons where terrorist suspects were detained and tortured during the George W. Bush Administration. And on Friday, Trump issued an executive order that suspended entry of all refugees into the United States for 120 days, barred Syrian refugees indefinitely, and prohibited entry into the United States for 90 days for citizens of seven predominantly Muslim countries. Academics against Immigration Executive Order has rightly characterized the ban as “unethical and discriminatory treatment of law-abiding, hard-working, and well-integrated immigrants” that “fundamentally contravenes the founding principles of the United States.” The Trump presidency is unlikely to be remembered for its vigorous championing of human rights but it is already producing powerful forms of resistance that may put human rights center stage in the United States again. Why, again?

The place of the United States in the making a global human rights order had in fact significantly diminished long before Donald Trump appeared on the political scene. Beyond the culpability of the Bush administration in the practices of torture in the wake of 9/11, the reticence of the American state to engage in the global human rights order has a deep history. Since the 1950s, the United States has been slow to embrace international human rights treaties and norms. The US Senate ratified the Genocide Convention only in 1988, some 40 years after it was adopted by the United Nations. In 2017, the United States remains the only country in the world that has not signed the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and is among only seven countries that have failed to ratify the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. The United States is also not a participant in the International Criminal Court, which prosecutes individuals for crimes of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. It signed the Rome Statute that established the court, but there has been vigorous and enduring opposition to bringing the statute forward in the Senate for ratification. The United States was the 22nd country to legalize gay marriage.

![African American homeowners Orsell and Minnie McGhee (center and seated, respectively) turned to the NAACP when a group of white homeowners sought to oust them from their home on the basis of a racially restrictive covenant. In what became Sipes v. McGhee, the NAACP argued that United Nations charter guarantees of human rights made such discriminatory covenants illegal. [Source: Archives and Research Library of the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History]](https://www.historians.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/human-rights-1024x841-600x493.jpg)

African American homeowners Orsell and Minnie McGhee (center and seated, respectively) turned to the NAACP when a group of white homeowners sought to oust them from their home on the basis of a racially restrictive covenant. In what became Sipes v. McGhee, the NAACP argued that United Nations charter guarantees of human rights made such discriminatory covenants illegal. [Source: Archives and Research Library of the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History]

Perhaps even more surprisingly, the reluctance of the American state to fully embrace global human rights is mirrored in contemporary civil society. Most of the major American social movements of the last decade—among them the Occupy protests, the Fair Immigration Movement, the Fight for $15, the Marriage Equality Movement, and Black Lives Matter—took primary inspiration from alternative political and moral lexicons. In their challenges to the mounting chasm in wealth and income between the top one percent of Americans and the rest, the mass incarceration of African Americans, escalating detentions and deportations of immigrants, and growing racial disparities in policing, education, and income, these movements could have turned to the language of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and its promises of universal guarantees to economic and social rights, to free movement, and to live without racial and gender discrimination. Even though at times they have made rhetorical gestures to the lexicon of human rights, their energies and tactics on the ground have operated largely around a domestic space in which structural arguments about economics and race at home are more believable than oppositional political discourses that draw on global human rights norms and practices.

It was not always so. In the 1940s, the United States was fully present at the creation of a global rights order and African American, Japanese American, and Native American activists embraced UN-sanctioned human rights norms to fight dozens of cases of domestic discrimination. For instance, in 1946, African American homeowners Orsell and Minnie McGhee turned to human rights guarantees of the United Nations Charter when a whites-only restrictive covenant threatened to remove them from their Detroit home. Three decades later, some 400 US-based human rights organizations were established as human rights became part of American professional practice. Doctors, lawyers, journalists, physicists, bankers, accountants, chemists, university and high school teachers, students, senior citizens, social workers, ministers, librarians, grants officers at the nation’s leading foundations, psychologists and psychiatrists, dentists, and even statisticians all found human rights in the 1970s.

To some extent they never let go. If the 1970s marked the beginning of human rights as vocation, the professional turn has only intensified in the 21st century. Human rights are now deeply embedded in the curriculums of most professional schools, from schools of medicine and law to business. There is a proliferation of undergraduate and graduate programs in human rights at US colleges and universities, with many of their graduates going to work in what is now considered “the human rights field” at nonprofits or in business. Indeed the quotidian spread of human rights into the fabric of contemporary American society can be quite remarkable. New York state fifth graders spend as much time reading the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as they do Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer.

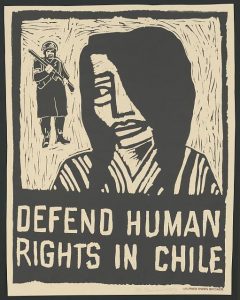

This 1975 poster designed by Rachael Romero and Wilfred Owen Brigade calls to “defend human rights in Chile.” Library of Congress

What changed between the 1940s and 1970s, however, was the location of American human rights concerns. In the 1940s, human rights were seen by many as doing political work both inside and outside of the United States. Campaigns against domestic and international rights abuses were deeply entangled. But when human rights were recovered and remade by a variety of Americans after 1970, the focus narrowed. Human rights offered a lens to understand problems far from American shores—in Brazil, Chile, the Soviet Union, Poland, or China. Only rarely did global rights norms play a role within social movements in the United States itself.

One week into the Trump presidency, the lines between violations of rights at home and abroad are already increasingly blurred with the nation’s airports becoming sites of detention. As the necessary resistance begins to an administration’s policies that gravely threaten the physical and mental well-being of the most vulnerable peoples among us, global rights norms potentially offer a set of vocabularies and practices that could mobilize Americans to once again make human rights a central tool for political action—just as they did for Orsell and Minnie McGhee in Detroit now more than 70 years ago. The language of human rights remains there for the taking today. Indeed the era of Trump could ultimately be remembered not just for the president’s own disregard for human rights but as the moment that marked the recovery in American civil society of the moral and political power of global human rights for our lives at home and in the world.

Established by the AHA in 2002, the National History Center brings historians into conversations with policymakers and other leaders to stress the importance of historical perspectives in public decision-making. Today’s author, Mark Philip Bradley, recently presented in the NHC’s Washington History Seminar program on “The World Reimagined: Americans and Human Rights in Twentieth Century.”

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.