A quarter century ago, I torpedoed my academic career by resigning from a tenured position with no prospect of another one. My ostensible justification was that my family would be much happier in Portland, Oregon, than in Prince George, British Columbia. But there was a part of me that wondered whether moving to the margins of academia might also benefit me, perhaps in ways I could not then foresee. Today, as I retire, I am convinced that giving up tenure made me, eventually, a much more effective, if less eminent, professor.

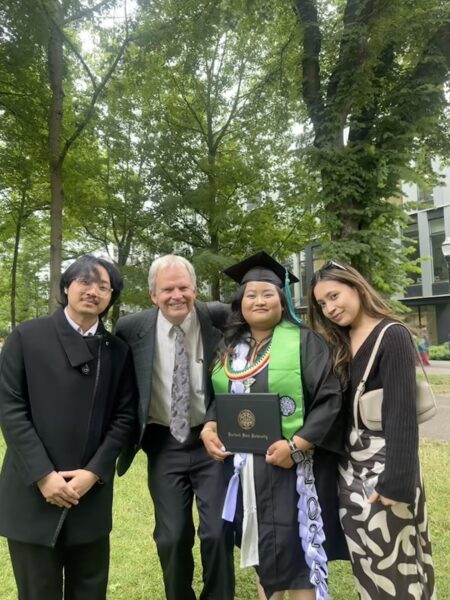

Freed from the strictures of tenure, David Peterson del Mar eventually focused on teaching first-year students and supporting them through graduation. Courtesy David Peterson del Mar

I was a model scholar for one decade. I finished my PhD at the University of Oregon in four years while publishing several journal articles and winning a Charlotte Newcombe Dissertation Fellowship. I accepted a job as the US historian at the brand-new University of Northern British Columbia. Harvard University Press soon published my first book, and I received a grant from the Canadian government to fund my second. I was promoted to associate professor three years after arriving and received tenure two years later.

But at this stage, I was wondering whether being a tenured professor would be as satisfying as I had assumed. The immense time and care I poured into my publications seemed completely out of proportion with their miniscule readership. Though I enjoyed teaching, it increasingly felt like a third priority behind research and university service. Perhaps giving up my tenured job would free me to write for a broader audience and explore other, as yet ill-defined, possibilities. I made the leap, quit my job, and moved to Portland.

I would write five books over the next 15 years, none of them widely read. But one made a big impact, though not to my writing career or scholarly reputation. The Boys and Girls Aid Society of Portland offered me $10,000 to write a history of their organization—more than the rest of my books had earned added together. It was not a book I would put on my CV, and it would not attract many readers. But, freed from the pressure of making an original scholarly argument, I found myself drawn to and inspired by the remarkable staff and volunteers I was interviewing, people deeply devoted to caring for traumatized children. And the book generated a great deal of enthusiasm—albeit from one person, a retired social worker whom I had interviewed. Every few months, she called to tell me how much she loved the book. Then she stopped calling. Years later, I learned that the book had brought her back to the organization, and that she left them a million dollars when she passed away. The only nonscholarly book I had written had evidently been the most consequential, funding programs that supported untold numbers of vulnerable Oregonians.

The only nonscholarly book I had written had evidently been the most consequential.

Moving to Portland also brought volunteer opportunities that involved more listening and engaging. I co-facilitated small groups with Oregon Uniting, a nonprofit devoted to furthering racial reconciliation through dialogue. A trip to Ghana prompted me to initiate a program of letter exchanges between schools there and in the Pacific Northwest. I co-founded the 501(c)(3) nonprofit Yo Ghana! with a high school student, and although I became the organization’s president and director, I quickly learned that doing more good than harm required deferring to a board of directors dominated by people in and from Ghana. We facilitated some 50,000 letters and supported 60 school-improvement projects. Yo Ghana! prompted me to volunteer with English-language learners, assisting highly dedicated high school teachers in their classrooms. This work was at times tedious, frustrating, and certainly humbling. But I enjoyed being stretched and, especially, collaborating with people I deeply admired.

My academic training was useful in these activities. Being able to absorb and interpret a great deal of evidence quickly was helpful, as was a historian’s habit of empathy, of understanding people from cultures very different from my own—whether a daunting headmistress in Ghana or a disengaged student in the local high school. My historical training also had taught me to write quickly and clearly and to not give up easily when projects did not go smoothly.

But I had to unlearn my habit of working independently and minimizing the time I spent helping others. Facilitating difficult conversations about race and racism, persuading teachers to add a program of letter exchanges to their packed schedules, cajoling alienated teens into caring about school—all this work required me to act as if I had nothing better to do than to be with these people. We were accomplishing a lot, but the accomplishments were often difficult to quantify or add to my CV, in part because they were the work of many hands, not just mine.

I was teaching as a nontenured professor all this time, usually at two or more universities simultaneously, and making a surprisingly good living at it. I had mastered the art of being a “good enough” teacher: civil, organized, able to lecture on a wide range of subjects, and willing to grade papers and answer emails promptly. That, certainly for the public research universities that I worked for, was more than adequate. No one seemed to expect more of me.

Then my department chair at Portland State University hopefully wondered whether I would take on a course that “no one wants to teach”: Freshman Inquiry. Persuading someone to teach that class was his “biggest headache.” It lasted the entire academic year, was required of most first-year undergraduates, and came with the assistance of a peer mentor, a slightly older undergraduate who led smaller class sections. Hungry for a more intense and meaningful teaching experience, perhaps something like I had found volunteering at the local high school, I decided to give the class a try.

It was in fact a difficult class to teach. I was assigned a course with the theme of Immigration, Migration, and Belonging, and the great majority of the students were from immigrant families. Most seemed anxious, certainly shy. I had researched and written about the history of immigration, but University Studies, the entity that oversaw our general education program, discouraged lecturing. So, for the first few weeks, I felt as awkward as most of the students seemed to be, so many of us wrestling with our own version of imposter syndrome.

Instead of lecturing, I tried a variety of new activities, including inviting students to share a meaningful story about their lives. And that changed everything. The students astonished me. I knew that many came from challenging backgrounds. But their particular stories—of missing large swaths of high school to earn money so their mother could make rent, having family conversations about which siblings they would be responsible for raising if the parents were deported, and even variations of “the dumbest thing I did in high school”—drew us into one another’s lives in a way that had never happened before in any of my classes. The compassion and encouragement they offered one another and the trust they had in me and our peer mentor also moved me. They were showing what sort of classroom they wanted, one suffused with care and collaboration: “like a family,” as some class members have put it.

At last I experienced in an academic setting the sort of community I found so often in my volunteer activities. And the more I focused on deepening my relationships with these students, the harder they worked. I required weekly personal reflections that I read closely and responded to at length, and several one-to-one meetings in which I invited them to talk about whatever they wished. Their attendance, performance, and retention levels rose. I was soon spending about three times as much time on the class as I was accustomed to.

Nearly 20 years after giving up my tenured position, I was again consumed by an academic job. But it seemed completely different. I worked largely with first-year students in general education, rather than history majors and graduate students. I had less job security, an inferior office, and, despite and because of my heavy teaching load, a smaller voice in departmental affairs. My closest colleagues were no longer ambitious scholars but rather university employees on the margins: peer mentors and contingent faculty who focused on students rather than research.

It was my academic priorities that had changed the most.

But it was my academic priorities that had changed the most. Rather than organizing my work around reserving as much time as possible for research and writing, I was now determined to devote as much time as I could to educating and supporting students whose prospects and, at times, lives seemed precarious. It was an easy choice; teaching and encouraging these young adults was by far the most important and joyful work I had ever done.

One of my young friends from Ghana, Dorcas Mensah, observed at the Skoll World Forum of Emerging Leaders in 2017 that “the idea of sharing your vulnerability or sharing your privilege with others has become inherently difficult in modern days.” As a white male academic, I think I understand what she means. My life circumstances gave me a big head start, but becoming a successful academic still required, I thought, a relentless focus on individual achievement and distinction. Research universities especially are organized around this assumption. Professors are therefore essentially rewarded for minimizing time with students, particularly struggling undergraduates. Only by stepping outside that environment for many years was I able to return to it with the intention and the capacity to see and support such students.

My opportunity to apply what I had learned outside the university to how I taught at university lasted only seven years. Along with nearly 100 other untenured full-time Portland State faculty, I received official notice in fall 2024 that my job was at risk. Many department chairs responded to declining enrollment by advocating that University Studies, our distinguished general education program, be phased out. So even if my position survived, the community that had nurtured my focus on serving underserved undergraduates might not. I chose to resign.

A quarter century ago, when I resigned from my tenured position, a colleague observed that it would be easier for me to find another spouse than another tenure-stream job. I suppose that he was right, and that my leaving academia prematurely now is a direct, if delayed, consequence of having put my family ahead of my career. Yet if surrendering tenure shortened my career, it also increased its impact, inside and outside academia.

After writing six academic books, David Peterson del Mar has collaborated with some fifty Portland State University students in publications about New Majority college students, including, with Alejandra Vazquez, Culture Clash (PDXOpen, forthcoming). He is grateful to Laura Ansley, Tim Garrison, Maurice Hamington, Kelly Nguyen, Emili Ortiz Villanueva, Estefani Reyes Moreno, and Alejandra Vazquez for their help with this piece.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.