In February I had the privilege of visiting a public university in the Midwest and meeting with students from its graduate history program, both masters and PhD candidates. I left very impressed: the department chair was dedicated and forward-thinking, the faculty were excellent, and the students were remarkably bright. One was researching the intersection of African American history with health and medicine. Another was working on a topic connected to LGBT history. A third was doing work connected to public policy. Eloquence, intellect, and precociousness were common to all.

Another thing they had in common, though, was anxiety about their future job prospects. It turned out that they had been inundated with messaging for at least as long as they’d been graduate students—and perhaps even longer—about the dire state of the academic and public history job market and their slim chances of landing a job using their degrees. The sum effect of this rhetoric was that the students felt adrift. They did not know what path to follow, were unsure whether they would succeed, and asked me if I could provide a clear roadmap that would ensure success. There was a palpable sense of frustration and the students wanted me to tell them how they could get an edge. This came on the heels of similar encounters I’d had at professional conferences, other colleges and universities, and here in Washington, DC.

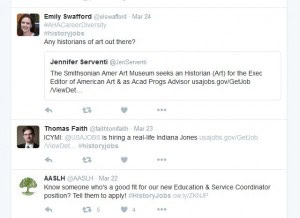

The #historyjobs hashtag on Twitter is a resource for history grads seeking a wide range of job opportunities.

This has all gotten me feeling that we in the profession may be doing our younger colleagues a disservice. These are historians who we want to be energetic, passionate, and encouraged about the future. Yet we may have beaten all the cheer out of them by belaboring the state of the current job market both within and outside academia. In fact, the AHA’s 2013 report on “The Many Careers of History PhDs” found that the overall employment rate for history PhDs was “exceptionally high.” Similarly, the national unemployment rate for those with a bachelor’s degree or higher is currently 2.5 percent. How about some optimism for a change?

To be sure, we must be pragmatic. The employment situation remains challenging across the nation and its pains are not confined to history, academia, or the humanities. Jobs in numerous fields are highly competitive and funding is tight across sectors. In government, where I work, it is not uncommon for several hundred or several thousand people to apply for one position. The same is true for many fields within the private and nonprofit sectors. Eight years since the Great Recession, the demand for employment still exceeds its supply.

However there are history jobs out there. A good resource is the #historyjobs hashtag on Twitter. Another is the AHA’s Career Center or the job listings of the National Council on Public History and Society of American Archivists. The positions advertised are not always full time—some are part time or project based—but they are bound to be right for someone at some stage of their careers. Through my #historyjobs posts I have shared jobs from institutions such as the Library of Congress, Smithsonian, Minnesota Historical Society, National World War II Museum, New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs, Huntington Library, Northwest African American Museum, Hagley Museum and more. My message to students is: Someone has to get those jobs. Why shouldn’t it be you?

I told the students I met in February that yes, it is competitive. You will compete against others with similar degrees and similar skills, and sometimes the hiring decision comes down to factors that are beyond your control. It’s no reason to get discouraged; it happens in every single profession. The market is competitive but you are competitive in the market. If there is a position, and hundreds of people apply for it, someone has to get it, and that someone may as well be you. The students had yet to hear that message. And they told me that it meant a lot to them to finally hear it.

There are things students can do to stand out. They can beef up their publishing credentials—in academic journals, on blogs, on online publishing platforms such as Medium or in the media (national or local). They can do internships and gain on-the-job experience. They can also diversify their skill sets so that they have what institutions are looking for. The AHA Career Diversity for Historians initiative, for example, has identified five skills that graduate students need to succeed in careers both within and beyond the academy: communication, collaboration, quantitative literacy, intellectual self-confidence, and digital literacy. I am also working with the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Purdue University to create the field of history communication and add media and communications training into the history training agenda. Historians should have the web skills, social media savvy, audio-visual editing capabilities, and excellent media and communications skills they will need to succeed tomorrow.

I have seen firsthand how damaging it is to young historians to have so much negativity in the atmosphere. We want them to be optimistic! We want them to be excited about entering the field. We want them to feel like there are opportunities even if those opportunities are competitive. I’m not sure we realize how much of an impression our collective pessimism may be having on those still in school. So let’s be more positive. Let’s tell people there are jobs. Let’s tell them you will be competitive to get those jobs, even if you have to try several times and take several routes to get there. There’s no reason why the one person an institution hires this year can’t be you.

Finally, my message to my fellow historians who are giving career advice and writing about the labor market is to do so with pragmatic optimism: realistic about the landscape, but positive about the opportunities within that landscape. There are jobs out there. Let’s tell our students that they have a chance of getting those jobs, even as we’re being realistic about the challenges that they may face through the process.

Photo by Amanda Reynolds

is a public historian at the John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress. He is the creator of the term history communicators and founder of the field of history communication. On Twitter: @JasonSteinhauer.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.