The ubiquity of the undead as protagonists in modern entertainment media—from novels to movies to video games—has exponentially increased student interest in the history of ghosts and zombies. Every age and culture has its stories about the returning dead, but teachers of premodern Europe are particularly well served by the abundance of accounts in English translation.

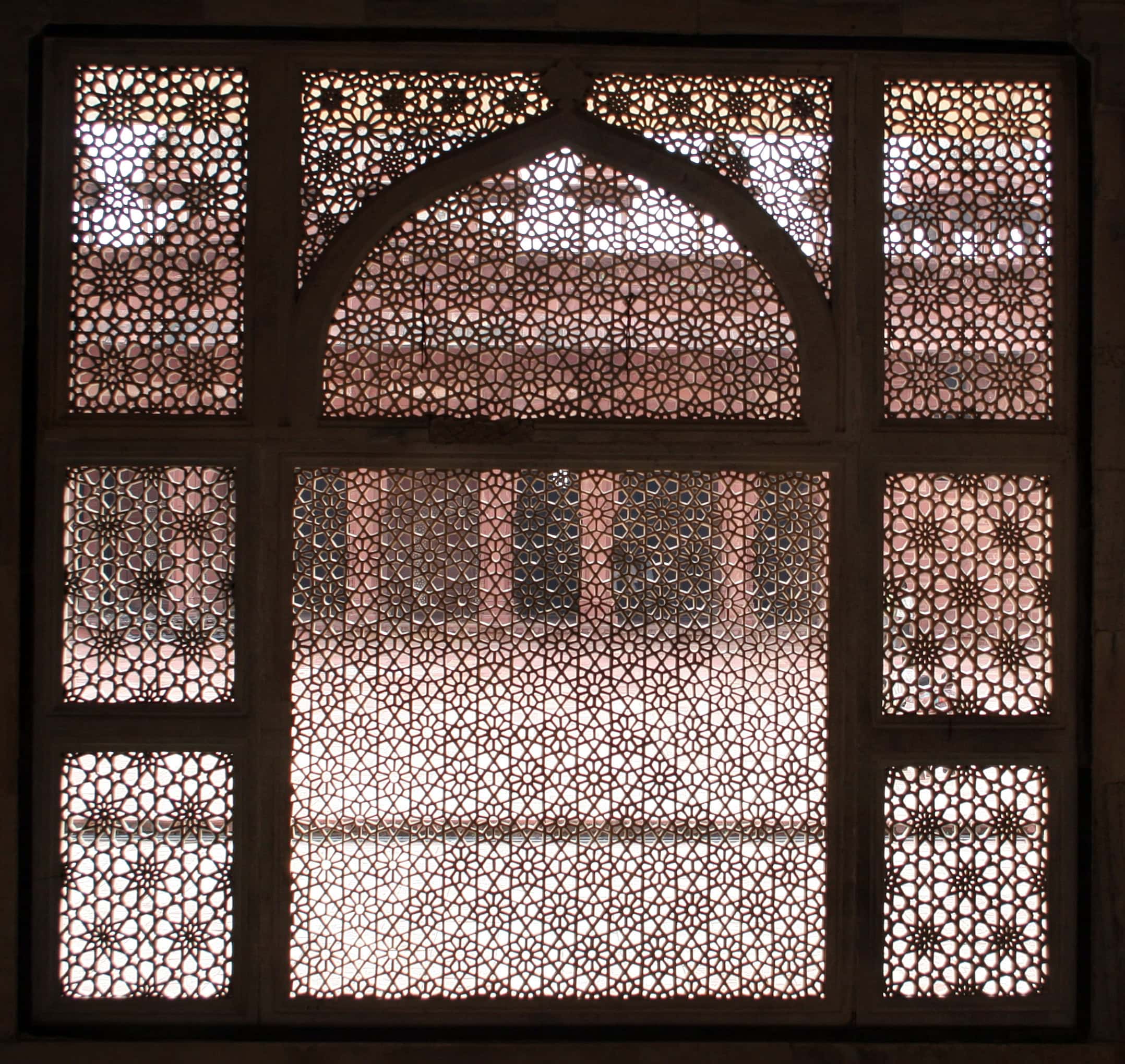

Ghost stories provide a rich literary and cultural tapestry for historical examination. Stowe MS 17, f. 200r. British Library. Public domain.

Ancient and medieval European ghost stories do not meet the expectations of modern tales of supernatural horror. They do not rely on shock tactics to frighten the reader, the ghosts themselves are typically not malformed in appearance or malevolent in intent, and the purpose of these stories is didactic rather than entertaining. Yet these tales are rewarding resources for teaching students about classical antiquity and the Western Middle Ages because they provide us with the opportunity to ask probing questions about how people in the past imagined the relationship between the living and the dead. From what otherworldly abode do the spirits of the departed return? What form do ghosts take, and how do they communicate? Why are they deprived of eternal rest, and what do they require from the living in order to obtain it? As rich and vivid cultural constructions, ancient and medieval specters give up valuable secrets about the worldviews of the authors who told stories about their return.

Most premodern hauntings followed narrative conventions. An unquiet spirit appears in a certain locale or to a specific individual, reveals the reason for its unrest, and receives help from the living to find repose in the afterlife. Ancient ghosts often reminded the living to observe proper funerary rites and thereby provide them with an easy passage to the otherworld. Such was the case with the hapless sailor Elpenor in Homer’s The Odyssey, whose ghost implored Odysseus to bury him according to custom after he died in an accident. Likewise, as recounted by Pliny the Younger, a nameless wraith seeking a respectable burial haunted a rental property in Roman Athens.

As centuries passed, the details of these stories changed to accommodate new belief systems. The meteoric success of Christianity in the fourth century triggered a groundswell of concern for the fate of Christian souls after death and modulated the urgency of their petitions from beyond the grave. While the teachings of the early church were clear that the soul lay in repose as though asleep until the resurrection of the dead and their judgment by God at the end of time, apocryphal writings like the Vision of Paul (composed ca. 400) depicted an afterlife immediately after death but preceding the final judgment, where human souls persisted in recognizable bodies that were vulnerable to physical punishments commensurate with their sins. In her eloquent book Moment of Reckoning (Oxford Univ. Press, 2019), Ellen Muehlberger has dubbed this alarming new phase of human existence the “postmortal.” It is from this liminal place between heaven and hell that the shades of the Christian dead return to our world, fretful of their eternal fate.

Ghost stories provide us with the opportunity to ask probing questions about how people in the past imagined the relationship between the living and the dead.

The dead remained stubbornly social in premodern ghost stories. As the notion of the temporary residence of souls in a punitive afterlife took hold in the Western imagination, so, too, did the idea that these spirits could benefit from the help of the living. Beginning in the late sixth century with anecdotes recounted in the Dialogues of Pope Gregory the Great (590–604), Christian apparitions returned to petition listeners to pray for their release from punishment in the hereafter. Pithy and memorable, these stories were primarily pastoral in purpose. The identity of the suffering spirits and the nature of their pleas provide us with a barometer of the kinds of people to whom Christian bishops and priests directed moral exhortation as well as the kinds of behavior that they sought to control. Pope Gregory’s audience was mostly monastic, and so, too, were his ghosts and their sins. Take, for example, the unfortunate Justus, a monk who hid three gold coins and suffered in fire after his death because of his greed until 30 days of consecutive Masses offered on his behalf by his brethren released him from his torment. Later imitators of Pope Gregory, such as Abbot Peter the Venerable (1122–56) and Caesarius of Heisterbach (ca. 1180–1240), tailored the details of these traditions to address new audiences, particularly laypeople, but they did little to alter the overall pattern of the narratives.

In the later Middle Ages, however, new experiences with the undead challenged the expectations of the ghost story genre. In the 12th century, for example, authors struggled to explain reports of animated corpses terrorizing villages in northern England. These were not the spirits of the dead returning to seek the aid of the living, but rather the bloated and bloodied bodies of notorious men, who rose from their graves at night to torment their neighbors with violence and pestilence. One was an infamous churchman known as the Hundeprest (Houndpriest), owing to his inordinate love of hunting, who terrified his wife by lurking in her bedroom before crushing her nearly to death with the immense weight of his dead body. Unable to find precedent for this phenomenon in “the books of ancient authors,” the monastic chronicler William of Newburgh was at a loss to explain how the dead were rising. His stories of rampaging revenants departed from time-honored literary models and anticipated a genre that would not find prominence until the early 21st century: the zombie survival guide. William’s breathless narrative related how a band of monks armed with axes and shovels waited in a graveyard by night for the dead man to rise and then, after a pitched battle, harried him back to his tomb. Once the monks had excavated his monstrous corpse, they destroyed it with fire, but only after they had completed the grisly work of extracting his “cursed heart.”

While ancient and medieval poets from Homer to Dante told stories about heroes and visionaries who visited the underworld to witness the fate of the fallen, the spirits of the deceased themselves have not played a starring role in the history of spectral literature until recently. A thought-provoking example is George Saunders’s experimental novel Lincoln in the Bardo (Random House, 2017). Set in the Civil War era, it features a cast of dead souls trapped in the “bardo,” a term for a liminal postmortal state borrowed from Buddhism. While the characters have been disfigured by the frustrated desires of their mortal lives, most do not even realize that they are dead. Their attention focuses on the newly arrived soul of a boy named Willie Lincoln, who tarries in this antechamber of eternity because the grief of his father, the famous president, tethers him unnaturally to the mortal world. In a reversal of a centuries-old tradition, the mourning of the living disturbs the repose of the dead.

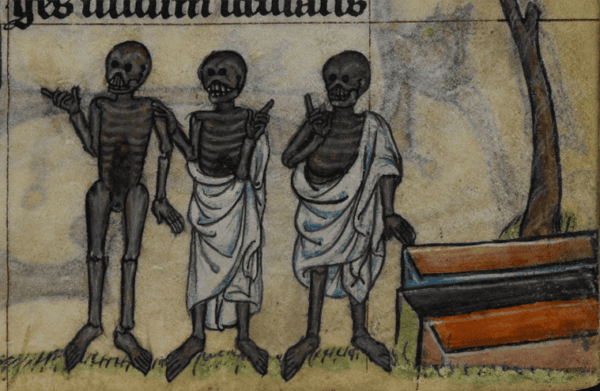

In Buddhist and Taoist traditions, the neglect of ancestors or misdeeds in life could give rise to “hungry ghosts.”

Underlying this rich literary tradition are fundamental questions of universal interest about the fate of the dead, the porousness of the boundary separating their world from ours, and the social obligations that the living had to provide for the deceased in their need. This attention to the memory of the dead and the responsibility of the living for their care was not unique to ancient polytheism or medieval Christianity. In fact, Western ghost stories shine most brightly as tools for teaching when they are read in tandem with tales of the returning dead from other religious cultures. In Buddhist and Taoist traditions, for example, the neglect of ancestors or misdeeds in life could give rise to “hungry ghosts.” These fearful spirits abided in the underworld, but they walked the earth during the seventh month of the Chinese calendar. In anticipation of their arrival, communities celebrated the Hungry Ghost Festival to provide symbolic sustenance not only to honor their own ghostly ancestors but also to ward off the ill will of the unknown phantoms in their midst. Like their Western analogues, the practice of the care of the hungry ghosts in Chinese culture is grounded on the hope that when we die, we, too, can rely on the living for help as we face the consequences of our mortal actions in the world to come.

The trappings of premodern ghost stories have been remarkably consistent in the Western tradition—Pliny the Younger’s chain-rattling Roman apparition could be mistaken for the ghost of Jacob Marley in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol (1843). The genre has also retained its didactic function down to the present day, but 20th-century authors have repurposed it in creative and instructive ways worth exploring in the classroom. Some modern tales about hauntings have doubled as narratives about the lingering trauma of slavery (Toni Morrison’s Beloved) and as warnings about the injustice of cultural appropriation (Hari Kunzru’s White Tears). Others aspire only to entertain with no higher purpose than to conjure the thrill of fear. A classic example is M. R. James’s 1904 short story “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad,” concerning a man who inadvertently summoned “a figure in pale, fluttering draperies, ill-defined” by blowing a metal whistle found in a ruined church. Read it by candlelight if you dare.

Scott G. Bruce is professor of history at Fordham University.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.