A look at the history hashtag network. Readers will notice the tags are organized into six major branches: Research & Writing, Annual Meetings & Seminars, Topical, Profession, Digital History, and Teaching.

On August 23, 2007, Chris Messina, a developer and pioneering Twitteratti, had a revolutionary idea. Messina tweeted to his followers, “how do you feel about using # (pound) for groups. As in #barcamp [msg]?” A hashtag, Messina argued, would improve “contextualization, content filtering and exploratory serendipity within Twitter.” In part, Messina’s proposal was meant to satisfy a looming threat to online social media. At the time, a number of social media users were withdrawing from open forums and embracing the concept of “whisper groups”—closed communities built on common interests. Fearing factionalism and its impact in online communities, Messina hoped the hashtag would satisfy users who wanted to be a part of a larger community, but still engage in more focused conversations and groups. Thus the hashtag was conceived as a tool to draw out the web agoraphobics and build directed conversation threads.

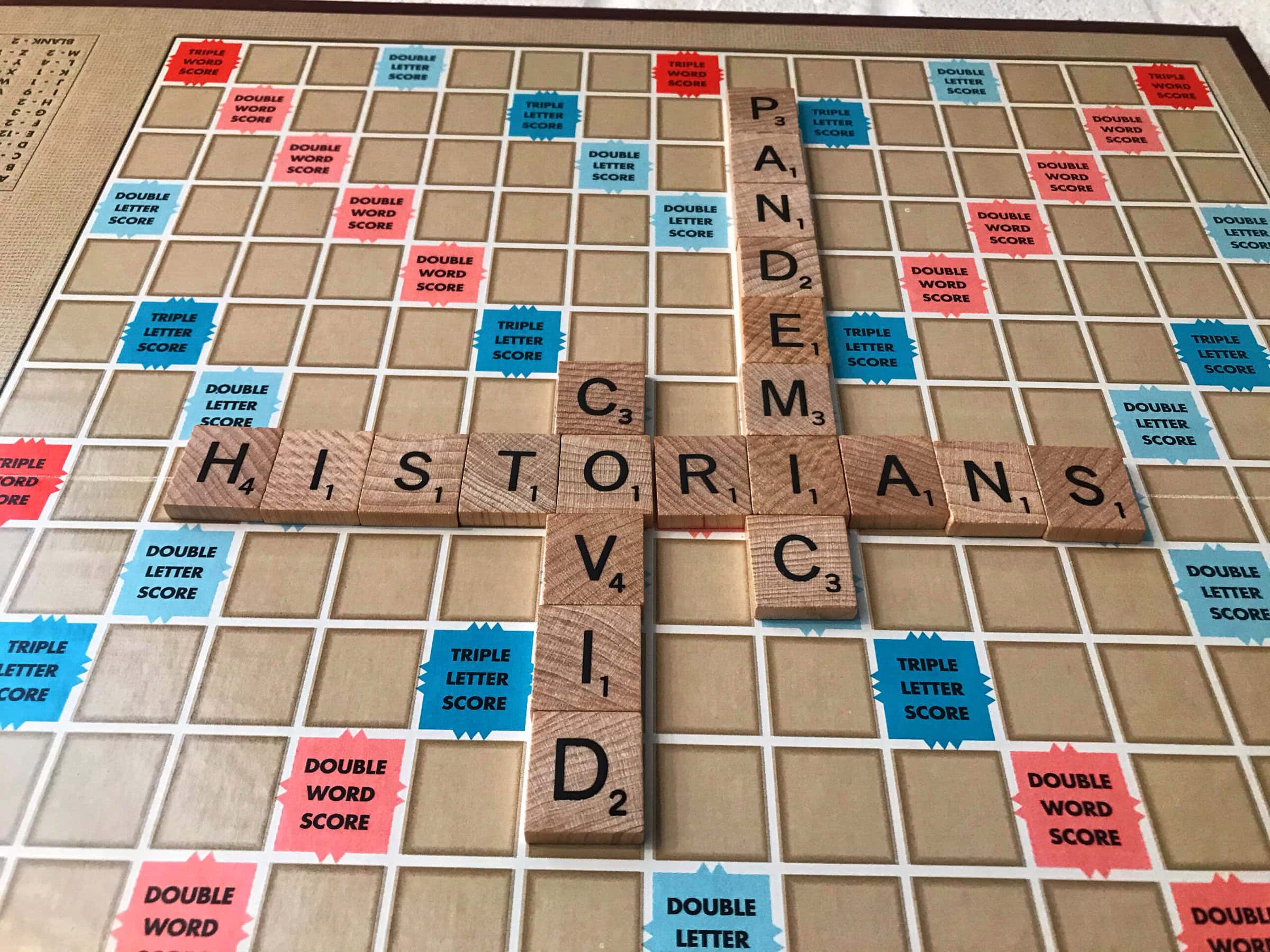

It’s interesting to trace the history of the hashtag, not only because it’s our business to look to the past, but also because many of the fears of fracture that Messina raised in 2007 are only just beginning to surface in the history Twittersphere. Over the summer I encountered these issues when I began to update a history hashtags compilation my predecessor Lis Grant originally created in 2012. When Grant first published the list, she found roughly 25 history-specific hashtags classified in two or three broad categories (topical, digital history, and profession). But in 2013, after asking #Twitterstorians for help updating the list and borrowing from another compilation from Liz Covart, our list grew to well over 100 tags that crossed professional issues, digital history, regional interests, and thematic research.

The Topical branch is the most complex, and includes Regional and Temporal subfields.

What began as a quick and dirty update had the potential to reveal much more about how historians are modeling the Twittersphere as a professional tool for scholarly dialogue. I assembled the hashtags into a visual interface using Pearltrees, an online curation tool that allowed me to organize the tags into tree-like structures, with group categories acting as branches. A visual interface, as opposed to a static list, reveals the impact and strength of each branch, and where we might be seeing large holes and gaps. While the main hashtags #history and #twitterstorians still reign supreme, it’s clear that historians are bringing their specializations to Twitter, and using hashtags to direct more targeted conversations. The topical branch, for instance, which holds regional, thematic, and temporal history tags, holds the most pearls. Noticeably bare is the teaching branch, with only a few tags related to #teachinghistory and the #teachingfails tag inspired by Richard Bond’s article in Perspectives on History (January 2013).

Shortly after I posted the visual guide, we received an additional surge of history tags from Twitterstorians. One response, however, struck me as particularly interesting and prompted me to consider some of the repercussions of this growth. @ProfessorMoravec tweeted, “intersting #dataviz of historians hastags we need fewer 2 b more effective. . . .” Her comment, in conjunction with the wave of suggestions from readers, led me to consider whether the proliferation of history tags is an altogether positive development. Are we only fracturing the conversation into smaller pieces?

It’s only natural that the history webisphere would begin to mirror the scholarly reality of our discipline, and I can only assume that as more of our colleagues join Twitter, so will the breadth of hashtags. There need to be defined spaces for specialists to share their research, circulate book reviews, and network, particularly because online interaction with colleagues can compensate for a lack of physical proximity with each other.

But we don’t want hashtags to help create echo chambers. Our discipline’s online presence is growing rapidly each day, leading to new audiences, new conversations, and new opportunities for collaboration. And yet it’s easy to find yourself falling into the same inner circles linked to your research, because it is safe and familiar. But confining your Twitter feed to familiar hashtags prevents the “exploratory serendipity” that Messina originally touted, and inhibits our community as a whole. We need historians to be active on #twitterstorians and #history, not just because these are our primary spaces, but because they are the first stop for people outside the discipline to see what the history Twittersphere is like, and we have a vested interest in putting our best foot forward.

There are a number of tools and applications to help users track multiple hashtags, including Tagboard, Keyhole, and TweetDeck. Tagboard allows users to monitor tags across multiple networks (including Twitter, Facebook, and Google+), while Keyhole not only tracks multiple tags, but also compiles analytical data about the tag, including popularity, timelines of the conversation, the number of users contributing to the thread, and total tweets. Finally, TweetDeck, now owned by Twitter, is an allaround dashboard that allows users to track tags in multiple columns, post new status updates, and schedule tweets. It has never been easier to expand your Twitter horizons.

I urge readers to take a look at the history hashtag guides created by Covart and myself, and experiment with new circles. See something missing on the list? Tweet us at @AHAHistorians.