Salaries for junior faculty in history departments experienced modest gains entering the 2011–12 academic year, even as salaries for more senior faculty continue to be squeezed by continuing economic difficulties for academia.

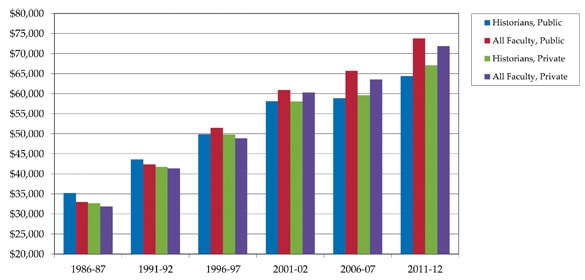

Figure 1: Average Salary Levels for History and All Fields, 1986–87 to 2011–12

The new information, in a report from the College and University Personnel Association for Human Resources, also highlights a widening gap in pay between history and other disciplines.1 For the current academic year, the average pay (not including benefits) for historians grew by just 1.5 percent, to $65,776. In comparison, the average salary for faculty in all disciplines grew 1.9 percent, to $72,938 (Figure 1).

Wide Differences in Growth Rates

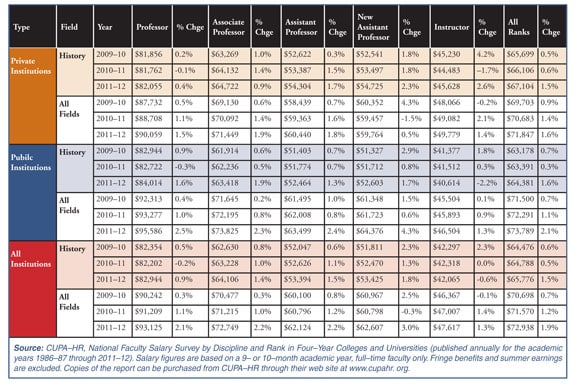

Diminished growth in salaries at the upper ranks of history pulled down the average for the discipline as a whole. The average salaries of full professors in history rose only 0.9 percent entering into this year, to an average of $82,944 (Table 1).

The slowest growth occurred at private institutions, where the salaries of full professors rose by a slight 0.4 percent (to $82,055). This marked the third year in a row that salaries for history faculty at the full professor level rose by less than half a percent. The salary increase for associate professors in history at private institutions also slowed, to just 0.9 percent last year.

Table 1: Salaries for Historians and all Faculty in the Academy, 2009-10 to 2011-12

At public institutions, full professors in history fared slightly better—as their average salaries grew 1.6 percent to $84,014. This increase marked something of a correction from a last year, when the average salary actually fell by 0.3 percent.

A number of history department chairs consulted over the past few weeks indicated that the decline in the average is the result of ongoing “salary compression” in the academy. Over the past four years, the number of senior faculty moving between departments has slowed noticeably in the annual Directory of History Departments. As recent economic cutbacks in higher education reduced the number of opportunities to take higher-paying jobs in other departments—or even receive offers that could be leveraged into salary increases at their current institution—salary gains for senior faculty have flattened out.

Even taking such changes into account, however, history salaries lagged well behind the average for faculty in all disciplines at the upper ranks, where salaries increased by 2.1 percent over the previous year. As a result, the average salary for full professors in history now falls 12.3 percent (or $10,181) below the average in all disciplines.

The trends were slightly better for newly hired assistant professors in history. They earned an average of 1.8 percent more than their counterparts a year earlier—growing to $53,425. Salaries for new assistant professors rose above the average for faculty at both public and private institutions, but rose a bit faster at private institutions.

Department chairs noted a number of factors for the gains among newly hired faculty. Some departments, noting the salary compression at the upper ranks, are working hard to lift the salaries at the entry level. Merry Wiesner Hanks (University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee) observed “if people don’t start with a decent salary, they may never have one.”

Other department chairs cited the growing professionalization of recent PhDs. According to Jeffrey Lesser (Emory University), recent hires “are negotiating hard, realizing how important it is to get a decent salary at the start.”

Even with these efforts, however, the increases in history still lagged behind the increases for new assistant professors in all disciplines, where the average salary for this year’s hires increased 3.0 percent to $62,607. The widest gap between the salaries of historians and the academy at large was for new assistant professors at public institutions, where the average salary fell 22.4 percent below the average (a difference of $11,773).

One of the other notable changes is the ever-widening gap between the highest and lowest paid members of the discipline. The highest paid professor in the discipline reportedly takes home $217,000 (at an unnamed public institution). This amount stands in stark contrast with the $18,478 received by the lowest paid instructor (who was also employed at a public institution).

Clues about Community College Salaries

In a separate report, CUPA-HR reports that the average salary for history faculty employed full-time in two-year colleges was $59,035, which was actually higher than the average for faculty in all disciplines (reported as $54,879). The gap in average salaries between the upper and lower ranks of historians in two-year institutions was also relatively narrow in comparison to four-year institutions. Full professors earned an average of $63,209 while assistant professors earned an average of $53,429. Members of the AHA’s Task Force on Two-Year Colleges report that the reported averages can be quite deceptive, however, as faculty salaries at some urban community colleges can range well into the six figures for some senior faculty.

The numbers reported by CUPA-HR should also be read with some caution. The data is based on a fairly small sample of institutions and faculty, due to the relatively small number of two-year colleges with discrete history programs. Past studies have also shown that more than half of all history faculty in community colleges are employed part-time, and are therefore not included in the figures here, which only tabulate results for faculty employed full-time. A forthcoming study from the Coalition on the Academic Workforce (which will be the subject of an article in the September issue of Perspectives on History) will explore the salaries and conditions of faculty at two-year and four-year colleges in greater detail.

Changing Demographics in the History Department

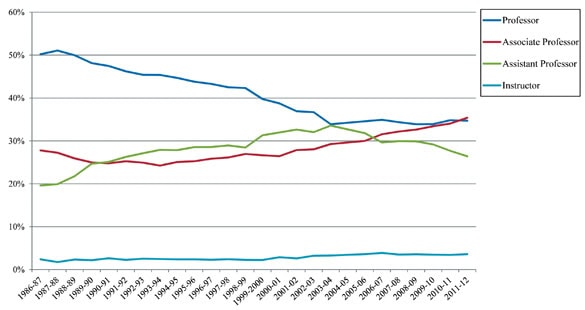

As a result of hiring freezes in many institutions over the past four years, history departments are now disproportionately comprised of faculty at the associate professor level—with faculty at that rank comprising a plurality of historians in academia for the first time in the past 25 years (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Trends in History Faculty by Rank, 1986-87 to 2011-12

Even as the proportion of assistant professors in history departments has fallen to the lowest level in 20 years—just 26.4 percent of the faculty members in departments this year. At the same time, the proportion of full professors has fallen sharply since 1986, when they accounted for fully half of the departmental faculty.

For the first time in the CUPA-HR data, the largest proportion of faculty at history departments are at the associate professor rank. This reflects two recent trends in history departments—a sharp increase in hiring from 1999 to 2007, followed by a sustained pattern of cutbacks and hiring freezes in many departments. As a result, the assistant professors hired in the early to mid-2000s are achieving tenure and entering the middle ranks, while a substantial number of senior professors have retired without replacements.

At the same time, three of the department chairs consulted for this article noted that a growing number of historians are getting stuck at the associate professor level. All three cited increased publishing requirements for the upper ranks—even at teaching-oriented institutions—and growing incentives to take administrative positions to compensate for the salary compression occurring in the faculty ranks. We do not have any evidence to independently verify that perception, but their unanimity on these points was quite striking.

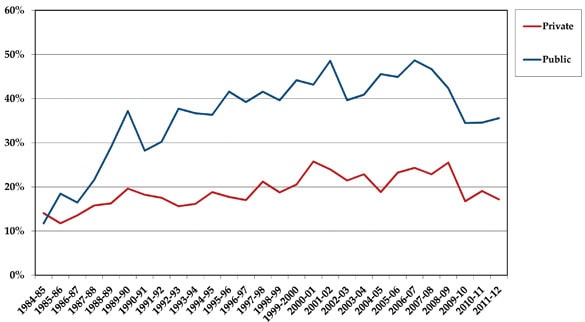

The one bright spot in the data was a small improvement in the number of new assistant professors hired last year, at least at public colleges and universities. That number increased from 157 to 173 last year at public institutions, as the proportion of public colleges and universities hiring increased from 34.6 to 35.6 percent (Figure 3). Even with modest gains over the past two years, the latter figure is still well below the highs seen in the earlier part of the decade, when between 45 and 49 percent of the public institutions were hiring new faculty.

Figure 3: Proportion of Institutions that Hired New Assistant Professors in History, 1984-85 to 2011-12

The news from private colleges and universities was more worrisome, as the number of new assistant professors hired increased by only one, to 86 last year, but the number of private institutions hiring actually fell from 76 to 67. The number of hiring institutions fell back to the same level as in 2009–10, the recent nadir of hiring at private colleges and universities. The slight increase in the number of assistant professors hired was buoyed by a relatively small number of institutions in a position to hire more than one new assistant professor this past year.

Viewed as a whole, the new report indicates that history is lagging behind much of the rest of academia, and points to a number of hard challenges that lie ahead for the discipline.

Note

- CUPA-HR, National Faculty Salary Survey by Discipline and Rank in Four-Year Colleges and Universities (Washington, DC: College and University Personnel Association, 2012). The report draws on data gathered from 813 public and private institutions, which reported on 224,693 faculty members. The average provided is only for a nine- or ten-month salary, and does not include any benefits. [↩]