On the one day between the first European winter storm of the year and a North American snow blizzard, I flew to Washington, DC, to participate in the 2018 AHA annual meeting. The United States and the Netherlands are both dealing with difficult issues regarding structural discrimination of certain groups in society, and both are engaged in vigorous debates about history and memory in the public sphere. I came to the AHA annual meeting hoping to get some new perspectives on these issues, and to see how historians in a different political and social context are tackling these debates.

History and Public Policy

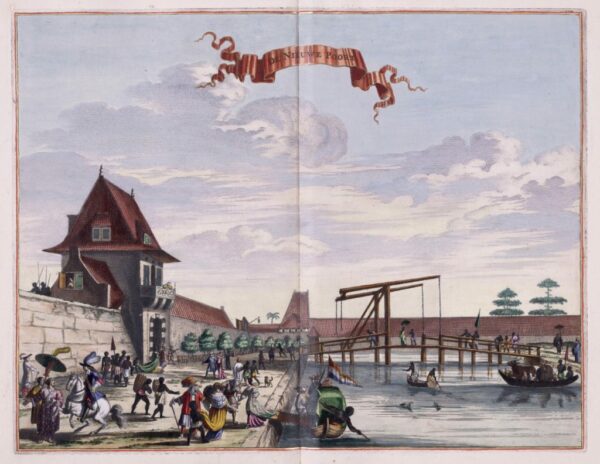

One paper on Dutch colonial history at the annual meeting focused on interracial marriages in Batavia (now Jakarta) in the 17th century. The image depicts the Nieuwe Poort at Batavia in 1682. Weduwe van Jacob van Meurs/Atlas of Mutual Heritage and the Koninklijke Bibliotheek, the Dutch National Library/Wikimedia Commons

I am the director of the Royal Netherlands Historical Society, the Dutch compeer of the American Historical Association. Although we are smaller, we face similar challenges as our American counterpart. One of these challenges is to continually prove the relevance of history and historical knowledge in a world that seems to revolve around tweets, opinions, and one-liners in the here and now. I chose to attend two panels that dealt with this issue at AHA18: one was a roundtable discussion on “History and Public Policy Centers” organized by the AHA’s National History Center, and the other provided historical perspectives on Europe “After Brexit.”

The first roundtable was interesting because it showcased the diversity of public policy centers and the differences in how they operate. Their representatives showed us that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to public policy. Some of these centers have a long and respectable history; others are relatively young and operate solely in the cyber world. The issues they address as well as the groups they focus on also differ. The Royal Netherlands Historical Society is considering starting a project on policy-making and history, but, unlike the AHA, we are not considering opening a center ourselves. We envision a working group in which members explore the needs of policymakers and provide historical context for current issues. This session helped me think about the first steps this working group should take—how we would like to operate and which group of policymakers we would like to address.

I was interested in the panel on Brexit simply as a European citizen. The panelists painted a dim picture of the current situation on my continent. Their analysis demonstrated convincingly the short historical memory of both politicians and citizens when it comes to the history of the European Union and political sentiment about this institution over the last 50 years in Europe. This panel was a good example of how history can provide a reality check to political delusions. For me, the most stunning example was provided by Deborah Cohen of Northwestern University, who took us back to the United Kingdom’s first referendum about the European Union in 1975. At the time, over 65 percent of voters chose to remain in the EU. Back then, the Conservative Party campaigned in favor of remaining because membership in the EU promised free trade within Europe, which benefited the British economy hugely. The Labour Party campaigned against the EU; probably a series of events both the Conservative Party and Labour Party nowadays would like to forget.

History and Memory

Just as the United States has been participating in impassioned conversations about the place of Confederate statues and memorials in public spaces, there is heated debate in the Netherlands about Dutch colonial history and how it is commemorated. Like in the United States, public debate in the Netherlands concentrates on the renaming of public institutions like schools and museums, and the removal (or not) of statues of colonial rulers.

The current debate in the mainstream Dutch media and on social media started while I was attending the AHA annual meeting. On January 6, Piet Emmer, a retired Dutch history professor, gave an interview to one of the leading national newspapers about his new book on colonialism, slavery, and migration. In this book and in the interview, Emmer criticized current historical research on Dutch colonial history. He compared history to “a foreign country” on which we project our (contemporary) ideas and values. He argued that colonization brought civilization to the colonized, and that historians too often overlook this. His comments sparked an avalanche of reactions, including one from Mark Rutte, the Dutch prime minister, who once studied history. In a radio interview, Rutte echoed Emmer’s words and said that people have to be careful in judging the past through “21st-century glasses.”

Interestingly enough at the annual meeting I found one panel where US scholars discussed Dutch colonial history. Coincidently, this panel also dealt with the role of women in Dutch colonial societies, which as a women’s historian was an added bonus for me. So I walked over, curious to learn the outsider’s perspective on my country’s colonial history.

“Women and the Construction of Racial Identity in Global Dutch Communities of the 17th and 18th Centuries” concentrated on Dutch rulers’ desire for stability in colonial societies and the rules and policies they imposed to achieve this stability. According to Erin Kramer of the University of Wisconsin, in the 17th-century, colonists in New Netherlands held a vision of shared space with Indigenous peoples. When Dutch women, however, violated the boundaries of race and gender, for instance, as tavern keepers selling booze or sex to Indigenous men, they were punished, fined, and even sometimes banished.

Deborah Hamer of the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture showed us that interracial marriage in 17th-century Dutch Indies was used to create stability in the colony as well as foster a (future) source of labor and soldiers. Interracial marriages in the Netherlands itself, however, were not recognized as legally binding, thus restricting the married men and women to the colonies. Nicole Maskiell of the University of South Carolina told us the remarkable story of a little black child called Philip, born in a well-to-do Dutch settler family in New Jersey, whose wet nurse was a white Welsh woman. In his court plea for freedom, Philip used his nurse and the color of her skin to strengthen his case.

Het smaakt naar meer

I thoroughly enjoyed my first visit to the annual meeting of the American Historical Association. I attended interesting panels and sessions, took away some new ideas for the Royal Netherlands Historical Society, and learned more about the history of my own country. Or as we say in Dutch “het smaakt naar meer’’—this annual meeting gave me an appetite for more.

This post first appeared on AHA Today.

Antia Wiersma is director of the Royal Netherlands Historical Society (KNHG), based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. The KNHG is the Dutch compeer of the AHA. Before she moved to the KNHG she was deputy director as well as manager of the Collections and Research Department of Atria, the Dutch Institute on Gender Equality and Women’s History. She tweets @grr68.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Attribution must provide author name, article title, Perspectives on History, date of publication, and a link to this page. This license applies only to the article, not to text or images used here by permission.