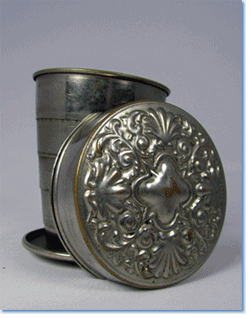

This slave cup was brought in by Warren Taylor, a former principal in the Omaha Public Schools. The cup, which has been passed down through the generations in his family, belonged to a relative who was a female slave in Mississippi during the 1840s. Taylor stated that the cup, along with an 1841 penny that came with it, were powerful reminders of how far his family had progressed over the roughly 150 years since the end of slavery.

A cup used by slaves. A dress worn long ago by a young Amish woman. Artifacts related to a Tuskegee Airman. These are a few of the items that students in our classes have digitized and exhibited in recent years through the History Harvest project. As a result of their efforts, these items and many others have escaped the obscurity of attics and closets and reentered the collective memory. Our students have thus advanced a movement to democratize and open the nation’s history by inviting citizens to share digitizations of their documents, artifacts, and stories for educational use and study.

We have involved our students in this exciting and rewarding work at the intersection of digital history and experiential learning by organizing History Harvests—community events in which students scan or photograph items of historical interest, brought in by local institutions and residents, for online display. Since the project started in 2010 at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL), these events have generated significant community involvement and media interest and proved extremely popular with our students, who have described their participation as challenging, rewarding, and transformative.

At each of these History Harvests—three at UNL since 2010 and a similar event at James Madison University (JMU)—we not only found new artifacts and documents but also sparked new conversations about history. Every family and community has a history, a connection to the larger story of the American experience, and in the History Harvest we explore those connections, talk about them, and document their meaning in partnership with the participants. Our aim is to make invisible archives and stories more visible, bringing them into the public realm to be shared, heard, and seen.

The History Harvest concept is flexible and adaptable. At Nebraska, harvests are organized by advanced undergraduate history majors in a special projects course devoted to planning and executing the harvest. Several students also participate in a year-long History Harvest Scholars program. The event at JMU was organized by 35 students, including many nonmajors, as one aspect of a course that surveyed U.S. religious history broadly.

We believe successful History Harvests must be organic, grassroots, and local. The particulars should depend on factors such as departmental needs, goals for students, and the creativity and ideas of the students involved. Organizing a History Harvest does not require specialization in public history or digital history, or even much technological expertise. More important to a successful History Harvest are the following suggestions:

1. Consider carefully the many histories represented in your community, and shape your collecting focus and strategies accordingly. You may invite community members to contribute any items they deem significant, or you may choose a focused theme, as Nebraska did by collecting items related to railroad history in its first harvest and as JMU did by concentrating on the religious history of four surrounding counties. Either way, harvests that are responsive to local contexts and concerns are more likely to generate widespread support and unearth the community’s overlooked stories.

“Teddy and the Bear” mechanical coin bank, 1904. Digitized by the History Harvest project, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. To see the bank in action, visit https://historyharvest.unl.edu/items/show/232. Used courtesy of William Thomas and Patrick Jones, UNL.

2. Explain clearly how you will use and treat the items you collect. The personal significance of the documents and artifacts people hold may be so great that they would never consider making a permanent donation. Emphasize at every opportunity that a History Harvest collects digital reproductions of an item and never keeps the original. Assure community members that their documents and artifacts will be treated with care, respect, and professionalism, and ensure that students and other participants receive training in how to work with such materials.

3. Collaborate with organizations outside and inside your school. The History Harvest project began in discussions with Nebraska public television and radio, both of which have reported on the events and played a key role in disseminating their findings to the public. The third Nebraska harvest, which collected local African American history, allied with the Great Plains Black History Museum, Love’s Jazz and Art Center, and the Malcolm X Memorial Foundation. Such partnerships can help allieviate community concerns about whether history is being expropriated. Collaborations with libraries and campus technology centers can provide the necessary equipment, technological expertise, and web site hosting.

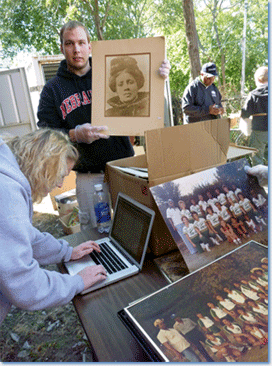

During the North Omaha History Harvest, University of Nebraska-Lincoln students inventoried and processed hundreds of artifacts from a storage container on the grounds of the Great Plains Black History Museum, which had been closed for more than a decade. Here, Matt Koziol and Jessica Hare work with a collection of photographs.

4. Give students a substantial role in determining how to organize and implement your History Harvest. In some cases, it will be enough to present the general concept, provide basic ground rules and guidelines, discuss examples of successful harvests, and ask students to develop and organize the harvest, in regular consultation with the professor and their classmates. Providing too much direction might actually interfere with one of the major pedagogical benefits of the event. Preserving open-endedness and flexibility offers students the opportunity to innovate. They will think of ideas you would never have considered, and they will relish the chance to build something of their own rather than simply implementing a preestablished plan.

This is the sort of hands-on learning experience that college history students often clamor for but too seldom receive. In large classes, consider dividing students into committees with specific areas of responsibility, such as event planning and outreach. If committees submit an action plan and report to their classmates and professor on a regular basis, they can work through problems as a class and hold students accountable for their individual contributions.

5. Raise the crop before you stage the harvest. The success of your harvest will be determined in large part by how creatively and effectively your class spreads the word before the day of the event. Students at Nebraska wrote a public letter to community members describing the event and asking for their participation and support. Students at JMU used personal contacts, visiting local ministerial associations, religious schools, and campus ministry groups. Well before the day of the harvest, a student had already secured the event’s single biggest find, a trove of documents and artifacts filling 18 banker’s boxes that had been lying neglected in the vault of a local Seventh-day Adventist academy. Outreach efforts should be multifaceted and tailored to the particular community or theme.

6. Maintain a steady work flow at a History Harvest. People who are kept waiting too long may decide to leave,taking their artifacts with them. If a donation is so large that it cannot be digitized on the day of the event, make arrangements to work with the material at a later time.

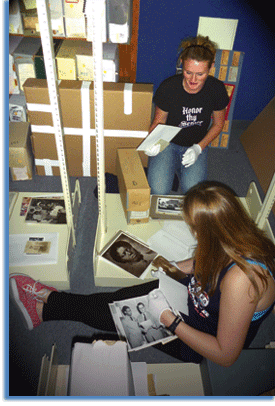

University of Nebraska-Lincoln students, Kelsey Jistl and Jessica Hare, help re-organize and rehabilitate one-of-a-kind archival holdings from the Great Plains Black History Museum during the North Omaha History Harvest in the fall of 2011. The GPBHM is one of the oldest African American museums and archives west of the Mississippi.

7. Collect oral histories and information about the artifact on the day of the event. This may be your sole opportunity to gather the supporting information that will allow scholars and members of the public to understand and interpret the digitizations you have collected. This is also the best time to obtain signed permission to display all digitizations online.

8. Schedule onsite educational programming for community members who attend your harvest. This may include a talk on the subject of the harvest by an historian or an opportunity for those contributing items to learn about their historical value from a team of professional historians, graduate students, and advanced undergraduates. Offer community members an opportunity to exchange memories and stories and discuss their items with one another. Schedule a public meeting after your digitizations are online to share what you have accomplished.

9. Build bridges between your institution and your community. Discuss with students what it means to serve as an ambassador of your institution, and look for ways to build stronger bonds with community members. One of the chief benefits for students will be the chance to actively engage and learn about the community, while exploring the ethical and political dynamics of history. Emphasize the democratizing aspects of the History Harvest: the way it invites more people to play a role in the work of preserving and studying the past, the opportunities it offers to augment the sorts of stories we tell about our communities, and how it expands our understanding of what merits preserving and remembering.

History Harvests, in all of their various forms, have the potential to be illuminating, celebratory, and transformative events for students and the public alike. At our harvests the scene is festive but earnest, enthusiastic but professional, with a sense of revival, renewal, purpose, community, and honesty. The History Harvest can make the study of history more exhilarating by forming connections between classrooms and communities, and by giving students the opportunity to change what we know about the past, and how we know it.

History Harvests Online

For examples of the stories and artifacts we have already collected through History Harvests, and extensive reference materials, including course syllabi, promotional posters, community letters, and press reports, visit the History Harvest website. Or visit the History Harvest YouTube channel. Also view examples of the JMU History Harvest.

For information about the History Harvest program, to run your own History Harvest class, to get involved, or to help support this innovative project, please contact the authors at wthomas4@unl.edu.

William G. Thomas is the John and Catherine Angle Chair in the Humanities, professor of history, and chair of the department of history at the University of Nebraska.

Patrick D. Jones is an associate professor of history and ethnic studies at the University of Nebraska and the author of The Selma of the North: Civil Rights Insurgency in Milwaukee (Harvard Univ. Press, 2009).

Andrew Witmer is an assistant professor of history at James Madison University. He earned his PhD at the University of Virginia.